The Mapping Practices of Catherine D’Ignazio

Catherine D’Ignazio is an artist, software developer, and educator. She leads the Experimental Geography Research Cluster at RISD’s Digital+Media program. Her artwork has been exhibited at the ICA Boston, Eyebeam, MASS MoCA, and the Western Front, among other locations. Her artwork is participatory and distributed—a single project may take place online, in the street and in a gallery—and involve multiple audiences participating in different ways for different reasons. Her practice is inherently collaborative.

“In the early days of the Internet, you had a handle,” D’Ignazio recalls. Hers is Kanarinka. “It was given to me by a friend from Montenegro. In Montenegran it means ‘canary.’” That explains one of the linguistic mysteries surrounding D’Ignazio. The other is the title of her collaborative, the Institute for Infinitely Small Things, which is both the name of a book (Analyse des infiniment petits (sic), pour l’Intelligence des lignes courbes, a seventeenth-century treatise on differential calculus) and a graduate school project of D’Ignazio’s.

“I’m interested in social and political things that we may not pay attention to,” D’Ignazio says. One is the evacuation signs peppering Boston streets. They all say Evacuation Route, with an arrow pointing in the direction you‘re supposed to head in the event of emergency. What sort of emergency is unspecified. There are, D’Ignazio notes, some hurricane-prone communities where such signs might be useful, but in Boston it could be weather or war, for all the signs say. I did happen to notice that one route would land evacuees more or less in my backyard.

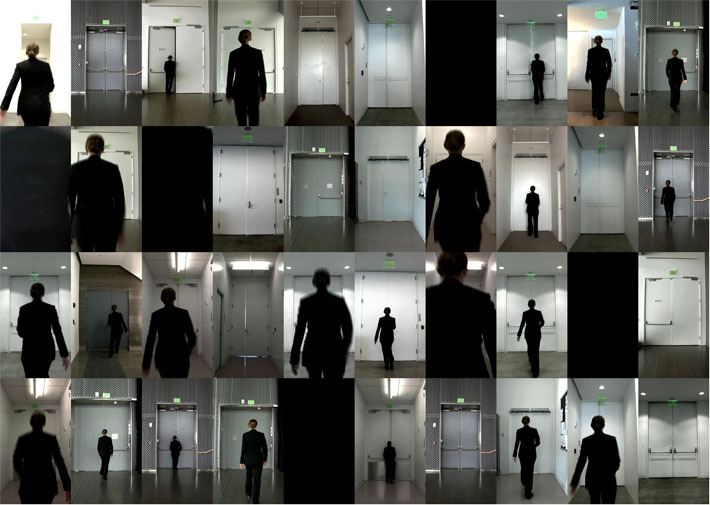

D’Ignazio, who has run the Boston Marathon twice, decided to run all the routes, which took her twenty-six trips—and a lot of breathing, hence the title of this project, It takes 154,000 breaths to evacuate Boston. She not only counted her breaths en route but also recorded them through sophisticated apparati. The resulting sculpture consists of twenty-six little bottles, each sized according to the number of breaths for that run, and each containing a speaker that plays the breaths from the run. In the version that turned up at the ICA, Boston, where she was a finalist for the 2008 Foster Prize, the evacuation map was on the floor, accompanied by a video of the artist passing through the ICA’s various entrances and exits. “An artistic attempt to measure fear,” is how she describes the piece.

As the evacuation piece suggests, D’Ignazio is one of many contemporary artists interested in maps. Others in the Boston area include Mags Harries and Lajos Héder, whose terrazzo map of water in Cambridge, down to residential swimming pools, forms the floor of the Cambridge Water Treatment Plant at Fresh Pond; and former Bostonian Leila Daw, whose map benches graced the DeCordova Sculpture Park in Lincoln.

D’Ignazio’s The Border Crossed Us, presented by the institute at UMass Amherst last year, is her photographic replica of a section of the fence that divides the US from Mexico in Arizona, erected as part of the Secure Fence Act signed by George W. Bush. It also divides the Tohono O’odham Nation, which occupied the area as a contiguous whole, long before the existence of either the US or Mexico. The fence, which sliced up even O’odham burial grounds, is “a manifestation of fear in the landscape,” D’Ignazio says. So was the UMass piece. “One guy [at UMass] said, ‘Is this going to be permanent? It’s really annoying.’“ Being annoying was part of the point, the artist says of this project, which had both poetic and political ramifications, dividing a space “that you consider yours, in its entirety, forever,” if you’re a member of the O’odham Nation.

Fear and wit are often teammates in D’Ignazio’s work. Consider Everything is in Order, a 2007 event by the institute held at the DeCordova. Wearing lab coats, the performers lined the museum’s majestic staircase, assuring visitors that everything was just fine. Anyone who has ever been to the serene suburban museum automatically thinks that everything is just ducky anyhow, and could only be rattled by the reassurance. Everything is in Order falls under D’Ignazio’s category of Homeland Insecurity.

Ditto for Unmarked Package, in which members of D’Ignazio’s institute lugged hundreds of packages so labeled around Chicago to poll people about terrorism. Then there’s her Origami Stimulus Package, a group effort by the institute and members of the MIT Origami Club, who held a party to make folded paper works from the 600-page federal economic stimulus package. She has also updated Dante’s Paradiso, replacing Dante’s heavenly god with a paradise of information, creating an installation at the Boston Center for the Arts with a grid of 256 LED lights surrounded by mirrors that controlled a Game of Life computer program that took input from visitors’ sounds.

D’Ignazio’s creative energy and invention seem boundless, although it’s clear that she owes a great debt to influences from art history to computers, which the thirty-six-year-old discovered at computer camp in the fourth grade. Her projects have an ongoing life on her website (www.kanarinka.com). A North Carolina native, she discovered art history while studying international relations at Tufts University. “I graduated at the height of the dot-com boom,” she says. Before graduating (summa cum laude) she spent her junior year in Paris, in museums. She has also spent time in Buenos Aires, studying computer science and film. She earned her MFA from the Maine College of Art in 2005, currently teaches at the RISD and MIT, and designs websites for clients. Oh, and in her spare time she is a wife and the mother of two very young sons.

D’Ignazio has written eloquently about art and cartography, noting artists’ impulses to map from the time of Vermeer, who depicted maps in his paintings, to the surrealists and such contemporary artists as Richard Long, whose “sculptures” consist of walks documented through photographs and installations of stones and other natural materials. She has a wry sense of humor, noting, in one long essay, that a map is abstract in the same way that a turkey recipe is: Nobody mistakes the printed instructions for the final outcome.

What engages D’Ignazio at the moment? She’s collaborating with costume designer Aleta Deyo and sound artist Mikhail Mansion on Back to the Land, a giant pink “joining suit”—the proposal looks a bit like a Christo—with head holes for ten people. Thanks to insect probes and low-frequency receivers, the occupants will connect with the land in listening sessions, meant as meditations on the harmony of land and bodies. Look for the ambitious piece on the grounds of the DeCordova this summer.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christine Temin was the art and dance critic at the Boston Globe for over two decades and now writes for a variety of international publications. She has taught at Middlebury College, Wellesley College, and Harvard University. Her most recent book is Behind the Scenes at the Boston Ballet, published by the University Press of Florida.