Gregory Gillespie: Transfixed —Selected Work 1995–2000

Gallery NAGA, Boston, MA www.gallerynaga.com

Through December 15, 2012

By Mary Bucci McCoy

The late Western Massachusetts painter Gregory Gillespie came of age as a painter in the 1960s. Rejecting the dominant paradigms of that era, and choosing to live in western Massachusetts rather than New York, he pursued a deeply personal, introspective path through idiosyncratic and eclectic realism often pushed in magical and surreal directions. Yet he was hardly an outsider artist, and by the time he died by his own hand in 2000 at the age of sixty-four, he had long had a very successful career, with gallery representation in New York (including a stipend) and Boston, work in significant collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and numerous exhibitions including a retrospective at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC.

Gillespie’s estate is now represented in Boston by Gallery NAGA, which is showing a broad range of work from the last five years of his life in this smartly selected exhibition. Throughout his career he unflinchingly tackled many of the classic genres of Western painting — portraits, self-portraits, landscapes, ensembles, and spiritual/religious works — and mined not just Western but global art history in his imagery and symbolism. The last five years of his life were no exception, as this exhibition demonstrates.

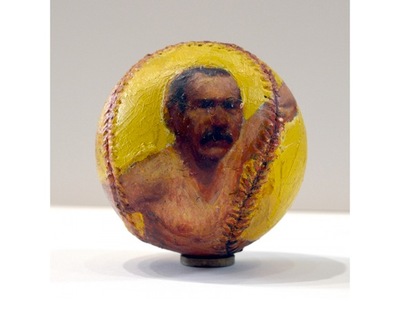

Gregory Gillespie, Baseball Self Portrait

An alternating current of hero vs. anti-hero crackles through this work. There is an ego statement inherent in the choosing of the self as subject, but Gillespie confounds that with his portrayal of himself: he was the conflicted hero of his own work. Self-portraits by definition offer opportunities for an artist’s personal and introspective work, and as such the four included here can be seen as the heart of the exhibition, offering a primer on the ways that Gillespie wrestled with his self. In Self-Portrait with Yellow Background he tries on Van Gogh’s brushwork and color palette; in hindsight it is eerily prescient. The titles of the other self-portraits suggest the anti-hero: Self-Portrait Sleeping, Self-Portrait with Banana, and Self-Portrait on Baseball. All three have self-deprecating humor, together with darkness, tenderness, and directness. In Self-Portrait on Baseball this is perhaps the most overt: Gillespie’s face and torso on a yellow-painted baseball is funny at first, but then when you think about the piece being used for its original function, perhaps less so.

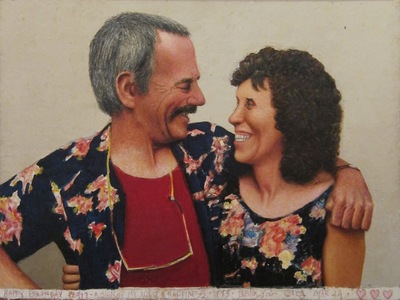

Gregory Gillespie, Pegs Grandmother 1998-99 12 x 34

If the gaze Gillespie turned on himself —and thus on the viewer—was fierce and unsparing, turned towards others it could be much more gentle. Peg’s Grandmother, his diminutive oil portrait of his wife’s elderly grandmother is at once earthy and ethereal. And in Greg and Peg he and his wife gaze smiling into each other’s eyes, their arms around one other. Scrawled at the bottom of the canvas are the words, “Happy Birthday Peggy—A sign of my love & happiness.”

Gregory Gillespie, Greg and Peg 2000 23 x 20

Gillespie’s painted world included not just the people in his life but symbols, often taken from other cultures or art history and informed by psychology. Manger Scene’s composition is a reference to European religious painting. It serves as a stage for him to bring together the multitude of techniques, actors and references that form a recurring vocabulary for him. In the background we see a village scene that brings to mind the work of Brueghel, perhaps a bizarre (to us) counterpoint to a female torso topped by a Mayan mask resting against a wall in the painting’s foreground. Also in the foreground is the nude figure of his wife Peg seen from the back, a reference to the absence of his mother who was committed to an asylum when Gillespie was a quite young. The blend of a personal iconography with universality again sets up a tension for the viewer, as does the play of realism against symbolism and surrealism within the unifying frame of the painting.

Once an artist dies, we can no longer approach their work as open-ended in the context of their oeuvre; we cannot wonder what will come next. The world and the art world continue on while the work remains fixed, so instead the questions are of the ongoing significance of the work. How does it continue to matter (does it continue to matter)? Does it have continued resonance for the audience? Does it influence artists? Or does it come to rest in the past? In the case of Gillespie’s work, he holds our gaze and we cannot look away.

Mary Bucci McCoy writes regularly for Art New England. She is a painter and designer who teaches at Montserrat College of Art in Beverly, Massachusetts.