Molesworth’s 80s Montage

Helen Molesworth begins her catalogue essay for the ICA, Boston exhibition, This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, by suggesting what she doesn’t want the show to be: “excessive, brash, contentious, too theoretical, insufficiently theoretical, overblown, anti-aesthetic, demonstrably political…” These were, until recently, she writes, all popular descriptors for the art that had helped make the decade infamous. This isn’t how she’d like us to remember the period, or, at least, this isn’t the eighties she wants to talk about: There’s a lot we don’t understand or know about the eighties, and yet it’s because we seem to be avoiding vast tracts of thinking from the decade. For Molesworth, it seems, the task for This Will Have Been is both revisionist and therapeutic. As our guide, she illustrates a lesser heard history with the politics of artists like David Hammons and Lorna Simpson, while re-situating the decade through a series of chafing juxtapositions like Mike Kelley and Mary Heilmann or Julian Schnabel and Leigh Bowery.*

Mary Heilmann, Tehachapi #2, 1979, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72″

Collection of David Doubilet

Molesworth points out that when two large-scale retrospectives on feminist art occurred in 2007, they skipped the 1980s. WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and Global Feminisms at the Brooklyn Museum, covered periods from 1965 to 1980 and the 1990s onward, respectively. A few months later, in 2008, Molesworth started thinking about This Will Have Been. The art of the eighties feels like an “open wound,” she writes, and this explains why there was what she calls a “blank spot” for the decade in the two aforementioned shows.

For many artists, the nation’s political left, and anyone who found themselves in the margins of society, the eighties represented a period like the Vietnam War, which a decade prior scarred the nation’s consciousness in a way that led to veterans becoming either public abominations or cartoonishly mythologized soldiers, like Rambo. The eighties didn’t have a war, but there was a national health crisis caused by HIV/AIDS. The disease eventually would kill more young men than the Vietnam War, but many were gay and so already considered moral anathema to a country being overswept by a conservative movement. The eighties also stood as a period of stagnation for feminism, according to the curator, caused by both a post-second wave backlash from the political right and a dilution of the movement’s efforts into more granular academic studies.

It’s difficult to understand the recent past because our closeness to it hinders our objectivity, and Molesworth jokes of the “hubristic folly” of trying to write a history of recent times. It’s not only because the powers that be are still battling for the narratives that will one day be impressed upon our children as truth, but—to take a word that Molesworth uses to describe the reception of so much artwork that was made in the eighties—the recent past is still “embarrassing.”

Jeff Koons, Rabbit, 1986, stainless steel, 41 x 19 x 12″. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

Partial gift of Stefan T. Edlis and H. Gael Neeson. Donald Moffett

Wounds, whether they’re psychological or physical, need working out, and this exhibition is very much part of the curator’s personal history. She is now in her mid-40s and witnessed the 1980s from her teens through early twenties. More than members of other living generations, the decade is a vested part of Molesworth’s personal and political identity. Her formative years were comprised of a time when people’s first loves and best friends were dying from a disease that the President of the United States would not even mention publicly until late in his eight-year tenure in office. “[G]iven the staggering loss of life experienced as a result of the HIV/AIDS crisis, pain attends the task,” she comments on her efforts organizing the exhibition.

Just as many Americans settled for revised narratives of the Vietnam War in cinema as a panacea for the injuries to their post-war national consciousness, Molesworth has produced a revised depiction of the eighties. Yet This Will Have Been is a survey of works that conform to an ongoing history of social progress. She selected artists that “register and negotiate the effects” of the “matured” social justice movements of the sixties and seventies and the concomitant rise of television. Many of the artists in the show were born in the 1950s and therefore belonged to the first generation to grow up with television in their households. Molesworth contends that her exhibition demonstrates that certain art from the eighties broadened our understanding of identity, explored politics as mediated through the still new public sphere of television, and brought about its own historical revisions.

Call the White House, 1990, Ciba transparency on light box, 40½ x 60½ x 63⁄4″

Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery and the artist

To accomplish her interpretation, Molesworth says the exhibition “narrativizes the decade from the position of memory and hindsight—with all of the open wounds, elisions, anachronisms, and blank spots implied therein.” As viewers, we need to be wary of terminology like “narrativize” because it suggests that any logic and chronology to the show are in the eye of the beholder. This may be rather annoying for those of us looking for the satisfaction of a pedagogical experience from the exhibition; its 130 works from about ninety artists may appear as though an unwieldy mess. We could be walking into an abstruse medley of eighties imagery that eschews popular historical movements for a political agenda, and realize nothing more than that the decade saw a global expansion of the art market as a few now-famous, non-American artists earned a spot in the show.

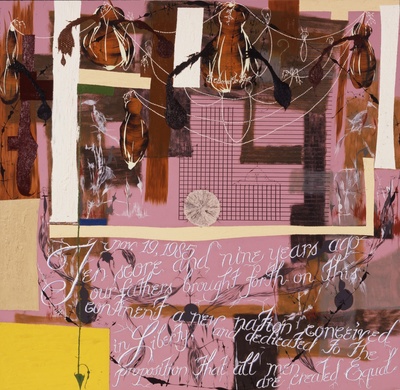

Molesworth declares early in her catalogue essay that the show does not attempt “to tell a properly chronological story of the decade,” and this was the style of the most influential critics of the decade. Such efforts could no longer pass the critical muster of cultural theory in this period. After Roland Barthes, Stuart Hall, et al., academia considered “narrative” a mere “construction of reality.” (Hall) This approach worked its way into the practice of many artists as well, such as the refuse-collecting Candy Jernigan. “As postmodernism heralded the end of humanist traditions, one was free to pick among the rubble and take what one found… in the spirit of an affectless reportage,” Molesworth writes of the framed crack vials in Jernigan’s Found Dope: Part II (1986).

Richard Prince, Untitled (cowboy), 1987, Ektacolor photograph, 20 x 24″

Rubell Family Collection

Affectless reportage did not, however, dominate the decade, and the polemical work of Lorna Simpson seems to be a microcosm for Molesworth’s organizational principles in This Will Have Been. Simpson was joined by artists Mary Kelly, German-born Hans Haacke, Chilean-born Afredo Jaar, and groups such as General Idea and Guerrilla Girls, in using the basic tools of mass media—photographs, iconography, typography—to provoke their audiences. Simpson’s photograph and text-based triptych Necklines (1989) is an almost Warholian repetition of the same photograph. Each repeated image, however, reframes the neckline of a black woman, each time connoting different meanings and conveying another narrative about race, identity, and representation. The work “insisted that new narratives needed new forms, that art was an opportunity to alter the way we tell stories in order to change the stories we can tell,” Molesworth states, and this is what she aims to do in This Will Have Been.

The task of a curator of contemporary culture is to play around in the sandbox of those things within close temporal proximity. Molesworth is on the experimental edge of history writing; she’s endeavoring to give us a fresh look at thirty-year-old imagery. Though what she’s presenting in here is a relatively diverse survey of art made between 1979 and 1992 in the model of montage, with its juxtapositions and lack of chronology forms of agitation.

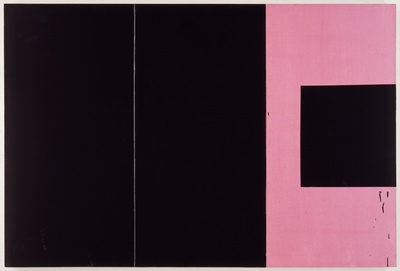

Molesworth divides the traveling exhibition into four sections: “The End Is Near,” “Democracy,” “Gender Trouble,” and “Desire and Longing,” but avoids the term “themes” to define their binding properties. As she told Bad at Sports in an April 2012 podcast interview recorded when the exhibition debuted in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, “themes” suggests similarities between the works in each section. Seeing the sleek geometry of a Mary Heilmann painting along with that of a similarly square Peter Halley in the “End” quarter of the exhibition is like opening an art history textbook, but a nearby landscaped collage of stuffed animals and Afghan rugs by Mike Kelley can fracture our view of the history of painting.

In the “Gender Trouble” section is a ten-foot work by Julian Schnabel, a painter who rose quickly in the commercial art world of the early eighties for his masculine, neo-expressionist paintings that revitalize a medium wallowing in what seemed to many a dead end of modernism—or at least that’s the story we know. The painting is a portrait of a shirtless, frail, Andy Warhol, and may be an easy target for a deconstructive look at maleness, but, as catalogue contributor Claire Grace writes, the work “posits masculinity as a contested cultural and corporeal space…” (296) Moreover, experiencing a Schnabel painting hung with photographs of Leigh Bowery sporting his costumes of formless androgyny or Cindy Sherman’s subversion of women’s representation in popular culture compels us to consider the constructive features of male gender.

Lari Pittman, The Veneer of Order, 1985, oil and acrylic on mahogany panel, 80 x 92 x 1¾”

Courtesy of the Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica

One might expect to see a shiny Jeff Koons sculpture in the mold of a readymade object in the “Desire and Longing” section of the exhibition. There are few works from the eighties more universally emblematic of such ideas, but what’s important for Molesworth seems to be less about having a Koons in the show than having a Koons be a part of the context she desires to create with her historical revisionism. The stainless steel, mirror-finished, Rabbit (1986) pulls the room together with you, the viewer. “[It] captures the gaze it has lured through its own its own gazing. All subjects must cope with the subjection and become things among things,” Elisabeth Libovici writes in her essay for the exhibition (319). Placing this Koons in the same section of the exhibition as Robert Mapplethorpe’s nudes, which repositioned black men within the visual lexicon of classical beauty, and Sherrie Levine’s eighteen copies of Egon Schiele self-portraits (Untitled (After Egon Schiele: 1-18) (1982)) shatters the hierarchy of image-making in a world dominated by straight male patriarchy. After the eighties, Molesworth seems to be saying, we could no longer believe there was an ideal or male-centric vision of beauty. Subjectivity and representation were up for grabs.

Many of the works in Molesworth’s “Democracy” section don’t rely on a recontextualization, but offer a record of the past either as benchmark to indicate how much society has changed, or reminder of how things remain unchanged. Works like Gran Fury’s Kissing Doesn’t Kill (1989), a photograph of three couples kissing, both interracial and intra-sexual, seems to have lost its potency, but the lesser the effect they have now has an indirect relationship with their efficacy in changing our perceptions of sexuality and AIDS. While other works like David Hammon’s painting of Jesse Jackson with a caucasian complexion and blue eyes How Ya Like Me Now (1988) or Hans Haacke’s oil painting of a smug Ronald Reagan connected by a red carpet to a photograph of a German protest against nuclear weapons (Oelgemaelde, Hommage à Marcel Broodthaers (1982)) still seem contemporary. Simply replace Jackson with Barack Obama or Reagan with Mitt Romney and the German protest with the Occupy movement and you’d have essentially the same works updated to our current milieu. “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” as the saying goes.

Still, This Will Have Been offers a narrative of progressivism that will empower the disenfranchised and, as its title implies, seems to sum up an optimism in historical revisionism. “This will have been” says that we haven’t yet fully experienced the future that Molesworth’s notion of the 1980s has wrought.

*Hall, Stuart. “The Narrative Construction of Reality: An Interview,” Southern Review. March 1984.

Note: The ICA’s version of the exhibition does not include all ninety artists in Molesworth’s traveling show. Holland’s article attempts to take on the entire breadth of the curator’s original vision as presented in her catalogue.

Christian Holland is a Boston- and Brooklyn-based writer, journalist, and essayist. He was executive editor and founding contributor of Big RED & Shiny, and now contributes to numerous arts publications. Follow him on Twitter at www.twitter.com/CRHolland.