The Indochina Arts Partnership turns Twenty-Five

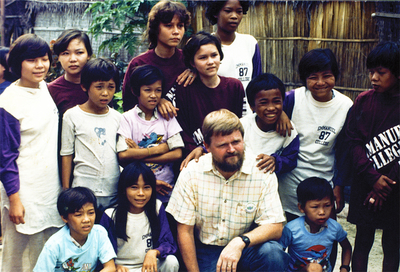

1987 photo of David Thomas on his first trip back to Vietnam since the American War.

Photo was taken at an orphanage for Amerasian children in Ho Chi Minh City.

In 1970, artist and soldier David Thomas was stationed in Pleiku in the central highlands of Vietnam. He was assigned to bring the camp’s laundry to a certain family in town. The parents and children he met were remarkable. A warm friendship evolved, re-enforcing David’s doubts about the conflict and the prevailing notions about the Vietnamese people. He would liked to have met more Vietnamese, away from the battlefield, that is.

In the mid-eighties, with no diplomatic relations and a US imposed trade embargo, Vietnam seem inaccessible. In 1987, however, Thomas approached John McAuliff, then director of the Quakers’ US/Indochina Reconciliation Project. (As an academic, David qualified to join the group.) He took along a portfolio of a dozen of his paintings, mostly showing Vietnamese children. He went to Hanoi’s National Museum of Fine Arts with the paintings, and knocked on the door of the Deputy Director Nguyen Van Chung. Thomas said, “He invited me in, looked at my paintings, and said, ‘Wonderful!’’’ David said, “They’re yours. They are about your country and your people.” Mr. Chung was very moved by the gift. Because of existing hostilities, they wondered, “What can we do to reciprocate?” They settled on a small exhibition at Emmanuel College, Boston, where Thomas taught. There would be two paintings each from two Vietnamese artists and two American artists. Eight paintings seemed to be a very modest endeavor. Yet it ballooned as the first major cultural exchange between the US and Vietnam; as such it would require dedicated work, money, and an umbrella organization.

The Indochina Arts Project, as it was then called (Thomas originally saw it as a unique, one-time effort) operated under the aegis of the Joiner Center at UMass Boston, which does for writers what the IAP now does for artists: exchanges and publishing. The show, AS SEEN BY BOTH SIDES, American and Vietnamese Artists Look at the War, consisted of twenty artists from each country, eighty works in all. I was to interview the artists and write the catalog. Bill Short would do the photography. David Kunzle, from UCLA, joined us as one of the curators.

Le Quoc Viet, Secret Mantra, 2009. Courtesy of David Thomas/Indochina Arts Partnership

In ‘89, we went to Vietnam to start the project. It was hardly a tourist mecca. We were not allowed to go to artists’ studios. They brought their work to us at the Hanoi Fine Arts Center. We chose work from Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. At home, we traveled all over America to select work, interview and photograph the artists. Some Americans, like Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, already were well known.

The preview opening was at the Arvada Center in Colorado. The major opening was at Boston University, poignantly, the very night we started bombing Baghdad. The show traveled to fifteen US venues and three in Vietnam. There were protests and cancellations. Because half the show came from communist Vietnam, many concluded that it had to be propaganda. Thomas counters with his belief, “You change people by working with them, not by isolating them.”

The Smithsonian Institution wanted to travel the show, but it was booked and revenue was needed to pay back loans accrued. David suggested to the Smithsonian that an exhibition celebrating Vietnamese culture and the beauty of the country be created. That idea became An Ocean Apart, featuring Vietnamese artists, half from Vietnam and half from the US, and with nothing about war. It was intended as a bridge between the two opposing Vietnamese factions.

By 1991, we were off again to Vietnam now as a non-profit 501 (C) 3 with the title Indochina Arts Partnership. Our new photographer was Bonnie O’Hara. Not only did the Smithsonian travel the show, but, in a sense, it kidnapped it. Caving in to pressure from well-known government conservatives who threatened loss of funding, the Smithsonian reformatted the nature of the show to have no forceful unifying aspect. It was a neutral art exhibition and Thomas refused to acknowledge it as his mission. My eighty interviews, which I wrote as essays, were handed to another writer to use according to the new public relations person. Thomas asserts, “That wouldn’t happen today.”

Recently there has been a steady stream of exchanges between the IAP and Vietnam—exhibitions in both countries, lots of print workshops, visiting artists, and lectures on contemporary art. One of the most spectacular took place in Thomas’s neighbor’s backyard in Wellesley. It was a 2010 installation by visiting artist Le Quoc Viet who painted old Vietnamese calligraphy on 150 silk tubes twenty inches in diameter and ten to sixteen feet tall. Since the French had Westernized the Vietnamese language, only monks and scholars can read it in the original, and Viet feared the language will be lost. Thomas’s neighbor had the perfect setting in which to suspend these elegant tubes.

New projects, such as documentary filmmaking in Hanoi, arise frequently. Not until a few weeks ago was the IAP able to take them on. Now, a close Vietnamese American friend, recently deceased, has established a foundation from which the IAP can obtain necessary funds for diverse projects. I asked Thomas how he felt about the twenty-fifth anniversary. “I don’t see it as an achievement. It [the IAP] has been such an important part of my life that it’s a way of life. Exhibitions come and go, but what’s really important are the lasting relationships.”

That the IAP is twenty-five years old is a wonder, something those of us who were with it from the beginning couldn’t have imagined. In 2000, David Thomas was awarded the first Vietnamese Art Medal for contributions by a foreign individual or country. Thomas and the country Japan were its finalists.

Artist, teacher and writer Lois Tarlow is a recent recipient of the Vietnam Art Medal awarded to foreigners for contributions to the arts in Vietnam.