LOOKING BEHIND-THE-SCENES

Given the wide-ranging nature of what museums do, there are many and varied challenges undertaken by museum people on a daily basis. These can be codified and listed in job descriptions. But what really drives museum people in their work? This compilation—a national sampling with a regional emphasis—reveals instead what personally motivates a variety of directors and curators. We look behind-the-scenes at eight candid stories.

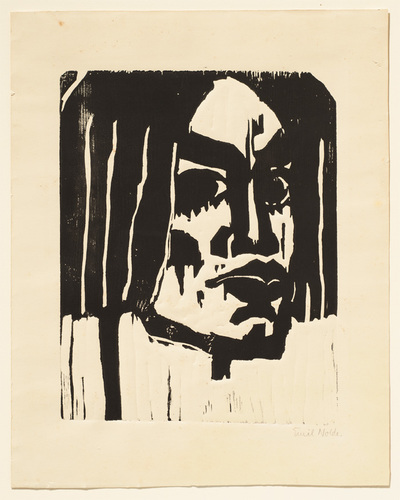

Emil Nolde, Head of a Woman III, 1912, woodcut on cream wove paper, 113⁄8 x 9″.

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, 2011. Image presented unaltered.

THE PERFECT VENUE: DESIGN MUSEUM BOSTON AT LOGAN AIRPORT

Sam Aquillano

Co-Founder/Director

Design Museum Boston

Design is everywhere. Our favorite websites, products, and buildings are all designed, but how often do we think about the who, how, or why behind the design of our desk, a subway map, or a hospital? Not often, unless we’ve had a bad experience—maybe our desk isn’t as ergonomic as we would like.

We started Design Museum Boston because there is great design all around us and it improves our lives. Our exhibitions are open to the public without charge, revealing the design process that shapes daily life. And just as design is everywhere, so are we. Instead of having a single gallery space, we are itinerant, and we install temporary exhibitions in places where people already go. We see the world differently at Design Museum Boston. Any public space is a potential gallery. Two years ago Massport had walked us through the airport looking for a gallery space. When we came upon Terminal E’s arrival area, it was clear we had found it. The beautiful glass and concrete structure would be the envy of any traditional museum. We spent the next year working with Massport to develop the exhibition to meet their important traffic and safety criteria, plus those of Transportation Security Administration (TSA). Security and durability were paramount considerations in this setting. Challenges of this sort were many.

In November 2012, we opened the fifteen plus lender show, Getting There: Design for Travel in the Modern Age at Logan Airport. From the moment you step into the airport you’re entering a world planned by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and a few hundred others. We highlighted designs ranging from luggage to the plane’s seats to flight-attendant uniforms to airport maps—from branded elements to those dealing with sheer comfort. Getting There showcases many designers’ efforts to create a comfortable, efficient, and exciting travel experience at Logan International.

Installation view, Getting There: Design for Travel in the Modern Age.

Courtesy of John Gillooly, Professional Event Images Inc.

FIRST AMONG EQUALS

Curatorial Department, the Institute of Contemporary Art

University of Pennsylvania

In a moment of unprecedented social connection, how do artists work together outside of their individual practices? Focusing on Los Angeles and Philadelphia, the exhibition First Among Equals, on view at the ICA last year, considered the various modes that contemporary artists have developed to work with their peers and reach across generations.

Cooperative, if at times contentious, contributions to the exhibition included performance, publications, curatorial projects, and artworks that incorporated the work of other artists. Who comes first in these relationships? By highlighting the dynamics of negotiation, dialogue, influence, contingency, and competition at work in contemporary artistic practice, First Among Equals resisted the notion that collaboration equals consensus.

We drew on the respective communities of the exhibition’s curators. Philadelphia participants included Bodega, Alex Da Corte, Extra Extra, and Marginal Utility and Machete Group. Los Angeles participants were Kathryn Andrews, P&Co., Mateo Tannatt, and Wu Tsang. In addition to participants invited by the curators, each artist or group included additional cultural producers in their projects, highlighting overlapping networks of peers as well as an expanded, intergenerational notion of community and influence. The exhibition and catalogue produced by program curator Alex Klein and assistant curator Kate Kraczon, exhibition organizers, documented the show’s five-month run, including its dynamic, numerous, and varied performances, events, and conversations.

Wu Tsang, The Fist Is Still Up, 2010, neon, acrylic on wood panel, 40 x 70 x 10″.

Courtesy of the artist and Clifton Benevento. First Among Equals, March 14–August 12, 2012,

Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania.

Photo: Aaron Igler + Matthew Suib/Greenhouse Media.

NEW COLLECTING INITIATIVES

Jay A. Clarke, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

Although the Clark Art Institute is best known for its collection of impressionist-era paintings and works on paper, the museum and research programs are always growing in new directions. Not only is the 140-acre campus undergoing a major expansion and renovation, to be unveiled in summer 2014, but the traditional collecting boundaries are shifting as well. In 1998, the Clark began to build a significant collection of early photography, focusing on works by American, French, and English practitioners during the medium’s first 100 years.

Yet another initiative focuses on strengthening our holdings of early twentieth-century art, specifically German expressionism. Between 2004 and 2013, the Clark has acquired etchings, woodcuts, and lithographs by Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Käthe Kollwitz, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The collection also has a modest, if strong, base of expressionism’s immediate predecessors, including Peter Behrens, Lovis Corinth, Max Klinger, and Max Liebermann, and a significant collection of prints by the movement’s spiritual forefather, Albrecht Dürer.

One example from this new group of prints is Nolde’s Head of a Woman III, a powerful woodcut from 1912. Like several members of the group Die Brücke, of which Nolde was briefly a member, the artist was interested in exploiting the expressive potential of the woodblock and using the uneven, raw nature of the block as a formal device. In Head of a Woman III, Nolde makes use of the repetitive vertical lines for the neck and nose, and parallel gouges in the block constitute the model’s hair. The square, structured form of her face and hair define their own margins, replacing the need for any formal border. The woman’s stark, even confrontational gaze belies the artist’s fascination with masks at this seminal moment in his career.

NOT SO FAST

Corrina Peipon, Assistant Curator

The Armand Hammer Museum of Art

In 2005, the Hammer Museum in LA launched an initiative to build a collection of contemporary art both through purchases and gifts. The collection has grown to include more than 1,700 objects in a variety of media, from drawing through video, made by artists from Southern California and around the world. While the Hammer is committed to collecting the work of certain artists in depth and to collecting its own exhibition history, it is also growing its holdings to include important works by significant artists from the post-war period to the present. If a work meets one of these criteria, the committee also discusses the merit of the work, its price, condition, and the storage costs that its acquisition would require.

Installation view of Selections from the Grunwald Center and Hammer

Contemporary Collection at the Hammer Museum,

Los Angeles, January 19–April 28, 2013. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Most works are approved or declined for accession during the meeting at hand. However, there are some that require more extensive deliberation or protracted discussion. Consider Nostalgia (2009) by Omer Fast, a celebrated artist born in Jerusalem, living and working in Berlin, and trained in Boston and New York. Shown in Selections from the Grunwald Center and Hammer Contemporary Collection, this work presented two primary challenges. First, its price exceeded anything previously purchased in the medium of video. When Curator Anne Ellegood, who proposed the acquisition, secured matching funds to purchase the work, the committee was able to approve its acquisition in good budgetary conscience. Secondly, the exhibition of Nostalgia has significant technical requirements. In addition to specific playback technologies, it requires a three-room installation with different display configurations in each room: a single-channel monitor; a two-channel, two-monitor arrangement; and a single-channel projection. These installation requirements constitute a commitment to the maintenance of the display equipment and to its physical configuration. Though it took nearly a year, the committee finally agreed that it was important to include Omer Fast in our collection and that the work in question was the right one for us to acquire.

THE WAY FORWARD

Nick Capasso, Director

Fitchburg Art Museum

As the new director at Fitchburg, my great opportunity is to reimagine this institution entirely. FAM consists of a complex of well-maintained buildings with 12,000 square feet of beautiful gallery space that occupies a city block in downtown Fitch-burg, an economically challenged city of 40,000 in north central Massachusetts.

The museum opened in 1927, and has built a strong endowment and a collection of over 4,000 objects that range from ancient Egyptian art and artifacts to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American paintings, with particular strengths in African art and the history of photography—along with significant art-historical gaps. The museum centered its identity on its collection and attendant educational programs for local public schools. For a host of reasons, this strategy proved unsustainable, and FAM now must overcome low attendance, insufficient staff capacity, insularity, and overall organizational inertia.

There’s no quick fix to this, but FAM’s staff, trustees, and external stakeholders have reached a loose consensus that the way forward involves a two-pronged approach: a massive injection of energy into the changing exhibitions program, and a renewed effort to connect meaningfully with the communities in Fitchburg and surrounding towns and cities.

FAM is now investing resources in exhibitions of contemporary regional art that link to our collections—something that we can afford to do with excellence—to connect past to present, interest new (and younger) audiences, and bring the museum rapidly into the twenty-first century. Simultaneously, FAM is creating a dedicated community gallery for shows of art from schools and community groups, instigating community-based public art throughout the city, re-connecting with educational partners (including the resurgent Fitchburg State University), becoming a bilingual museum (40% of Fitchburg residents are Latino), and actively assisting the city to create a designated downtown cultural district and low-income artist housing. We’re testing a new identity/goal/mission: To become one of the best community museums in America, however we might imagine it.

THE COLLECTING/DONATING AXIS

Mark Pascale, Curator in the Department of Prints and Drawings

The Art Institute of Chicago

Making acquisitions for a large art museum with an encyclopedic collection is always difficult. Art is expensive, and taste can be fleeting. One of my jobs is to encourage donors in their collecting, and hope they will make gifts to help us develop the collection.

In 1999, I met a collector interested in learning about drawings, after collecting prints, paintings, and sculpture with passion for about thirty years. He was focused on art of the 1960s—a plus for us at the Art Institute because the museum had not collected minimalism, post-minimalism, or conceptual art on paper in much depth. Over eleven years, I consulted with the collector intensely; we sometimes traveled together, meeting with dealers who specialized in drawings, and sometimes visiting museums and private collections.

Often, the museum was offered a work for which we had no ready funds, and we would have lost the opportunity to acquire it had I not been able to turn to the collector and request he buy the work and make it a promised gift. He repeated this process many times, so many that it became clear that his benevolence should be marked with an exhibition and book to celebrate his 106 partial and promised gifts to the Art Institute. It’s a habit that has continued, and having such a willing donor has made it possible for us to pursue parallel acquisition strategies with discretionary funds that otherwise would have been earmarked for the gifts we have and will receive from him over time.

Among the outright gifts that we received from this collector is a major drawing by Jasper Johns, a group of ten early drawings (and eight related sculptures) by Mel Bochner, two early works by Dorothea Rockburne, as well as partial interest and

commitment to finish giving a group of forty other drawings, with more to follow.

A MYSTERIOUS, HANDSOME MAN AND COLLECTION CONUNDRUM

Amy Ingrid Schlegel, Ph.D., Director of Galleries and Collections, Tufts University

Many university art collections have conundrum objects like this one that languish in the “Unidentified Dead White Male” inventory of portraits, a dime-a-dozen in this post-identity-politics, supposedly “post-feminist” era. Unidentified portraits, as this one was for decades, are often referred to as “objects found in the collection,” or “orphans,” which, after due-diligence measures to identify them are undertaken, may be legitimate candidates for deaccessioning and sale. In this particular case, we were hesitant to try to liquidate the painting, and not only because it would probably not bring much, if any, monetary reward, but also because this portrait had hung for as long as anyone could remember in the same, prominent location adjacent to the President’s Office in Ballou Hall, the first building built when Tufts was founded in 1852.

Unknown artist, Portrait of Hosea Ballou as a Young Man, date unknown (19th century), oil on linen.

On loan from Carla Ricci, EL 1991.1. Image courtesy Tufts University Art Gallery.

Our due diligence seemingly spent, we put the painting before the University Gifts of Art Committee, which I chair, because it had become our favorite “orphaned work.” It was accessioned in 2010. The consensus that was this well-coiffed young man was “eye candy” and had simply come to be called the “Handsome Man.” The mystery of its identification and provenance presented a kind of provocative flirtation with which we wanted to continue.

Last summer, during some belated collections archiving undertaken by an enterprising intern, Aimee-Michelle Pratt, a conservation receipt from the Fogg Museum at Harvard was found with a description of a painting matching the Handsome Man. The receipt had the name of a retired administrator, who had purchased the painting at auction in 1990 and had it conserved at the Fogg prior to bringing it to Tufts in 1991. Important clues were lost in the shuffle as university property inventories were just beginning to be computerized; in that same year, the Aidekman Arts Center was dedicated, and its focus was on the presentation of new, not older, art.

Intended as a long-term loan to stay on view “in perpetuity” in that same spot (though no loan agreement has been found), that retired administrator clarified that she still did not wish to donate the object. So in November 2012, the painting that was accessioned in 2010 was then put to a committee vote to deaccession.

Once in touch with the lender, we learned the identity of the mysterious Handsome Man: the young Hosea Ballou, one of the founders of Tufts who became a minister in the Universalist church. Our hope is that the lender will bequeath the portrait to Tufts, where it will once again become part of the permanent art collection.

DU BOIS IN OUR TIME

Loretta Yarlow, Ph.D., Director of the University Museum of Contemporary Art UMass Amherst

A special 2013 exhibition at the University Museum of Contemporary Art (UMCA) will ask what happens to an artist when she has the opportunity to try out her ideas through dialogue with scholars who have studied, taught, and written about W.E.B. Du Bois’s work for decades. In turn, it will ask what happens to a scholar when her work goes through the process of collaborating with such artists. How does artistic expression serve as a method of scholarly research and discovery? What kind of new understanding occurs to viewers as firsthand witnesses to the crucible of artistic creativity?

Radcliffe Bailey, Windward Coast—West Coast Slave Trade, 2009–2011, piano keys,

plaster bust and glitter, dimensions vary (approximately 27 square feet).

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY.

Du Bois in Our Time is part of the UMCA’s multipronged initiative to integrate artists within the artistic, programmatic, and institutional dimensions of the museum and UMass Amherst. Through Dialogue with a Collection, artists are annually invited to engage with and do research in the UMCA’s permanent collection. The experience culminates in an exhibition in which their works are integrated with others they select from the museum’s collection. Dialogue offers a rare opportunity to showcase artworks owned by UMass while being a supportive platform for invited artists. We set a new paradigm for this type of exhibition organization, using the vast W.E.B. Du Bois Archives and Collection at the university for many artists’ research. The UMCA is commissioning internationally acclaimed artists whose work is socially engaged and research-based to offer an aesthetic contribution to the rethinking of Du Bois, one of the most extraordinary public intellectuals in American history, through the lens of the twenty-first century.

Nothing honors the multiple talents, broad vision, and creativity of Du Bois more than using his life’s work to convene a new way to define and exemplify interdisciplinary imagination. Participating artists include: Radcliffe Bailey, Mary Evans, Brendan Fernandes, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Julie Mehretu, Ann Messner, Jefferson Pinder, Tim Rollins & K.O.S., Mickalene Thomas, Ultra-red, and Carrie Mae Weems. Their specially commissioned artworks will be created through a process where research, access to the Du Bois Archive and Collection, collaboration, and correspondence with Du Bois scholars informs an innovative, generative approach to artistic production highlighting disparate modes of understanding.