JAZZ IS PLAYING AT BATES COLLEGE

Wadsworth A. Jarrell, James Carter Trio, 1999, acrylic on paper, 11 x 14″.

On loan from Eric Key.

IF AN ARTIST COULD COMMUNICATE his message in writing, he would be a writer. If a writer could communicate her message visually, she would make paintings, not books. This is the trouble that comes with working across media. How does one bridge them?

An art writer overcomes this predicament by writing around the art—talking about history, context, backstory, etc.—or by over-describing the detail and minutiae of an artwork, or by writing about the consciousness from which the art was made. A similar hitch applies when an artist makes art about music. One doesn’t draw a symphony. One doesn’t carve a country song. What one does do is engage a series of strategies that brings the viewer closer to the experience of the music, that celebrates the community from which the music comes, and that taps into the consciousness out of which the music flows. Exactly how a group of artists does that is the subject of Convergence: Jazz, Films and the Visual Arts at Bates College through December 13, 2014.

Convergence is the product of a collaboration between the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, MO, an institution dedicated to the preservation and advancement of “America’s only indigenous art form;” and the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, College Park. Curators from both institutions brought together more than 40 works from their own collections, private collections and artists, as well as selected films from the John Baker Film Collection. Convergence was previously presented at the American Jazz Museum, from November 8, 2013 to April 27, 2014.

The exhibition has its share of documentary photography. Los Angeles-based Bob Barry has made a career of photographing jazz performers. Nancy Wilson sits on a stool in a long, beaded gown leaning back into her song. Ernie Andrews winces, mid-note. One hand holds the microphone while the other waves a napkin. Ray Brown has a moment in the studio, his arm draped over his double bass. Familiar photographs like these are a staple of music promotion. They convey a sense of the performer to a potential audience. They are technical and, in the case of Barry’s work, beautiful moments.

Other artists in Convergence trade in representation differently. The silhouetted quintet in Lila Oliver Asher’s linocut, Basin Street Blues, is bathed in a blue cloud. The title of the work refers to a song made popular by Louis Armstrong about a street in New Orleans’s storied Storyville neighborhood, the red light district where a number of jazz performers got their start playing in brothels. Asher’s musicians are nameless. The print is about a moment in time—a moment immortalized in music. Robin Holder’s stencil monotype, 112th Street and Lenox 5, is a shout-out to a block of Harlem that, in the 1930s, was the center of the jazz universe. These works conjure history and remembrance.

David C Driskell, Five Blue Notes, 1980 Encaustic and egg tempera on board, 22 x 29½”.

Gift of Nene Humphrey.

One artist in the exhibition, Harry Smith, wrote about his artmaking, “It’s not just the music and the personalities but the diversity, spirit, and freedom that it presents and represents.” Smith’s 2011 collage and acrylic painting Coltrane illustrates how these artists draw a thread through music, art, and history. Saxophonist and composer John Coltrane took the genre from the popular bebop to a mystical avant-garde free jazz that revolutionized the music’s potential. Before his death at age 40, Coltrane organized more than 50 recording sessions and worked with legends like Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, and Eric Dolphy. Not only an important figure in music, Coltrane is a symbol of the African Diaspora’s ability to thrive in the face of oppression. (The African Orthodox Church canonized Coltrane in 1982.) Smith’s portrait of Coltrane playing a saxophone is a beautiful homage to the man. The self-taught Kansas City artist renders a raw, broad-stroked drawing of Coltrane in his expressive style. Images of music and historical figures are pasted into the crown on the figure’s head. The liner notes from Coltrane’s 1965 album Kulu Sé Mama—the last album released in his lifetime—are pasted in the background. The portrait was first displayed at the American Jazz Museum in 2011 alongside a poem by Glenn North that ended “wielded his ax with the skill of a killer / through the thick anti-black forest / all praises, all praises for St. John.”

One cannot separate jazz from the African American experience and the 150-year post-slavery pursuit of freedom. The genre’s roots in African counter-metric rhythms brought by slaves, homophonic church hymns of rural spirituals, and Afro-Caribbean tresillos came to-gether because of the historical circumstances of freed slaves in the American South. Drumming was against the “Black Code” during slavery. After the Civil War, freed slaves were able to obtain surplus military instruments. During Reconstruction, employment opportunities for African Americans were scarce and performing music provided both a means of work and a way to improve one’s economic situation

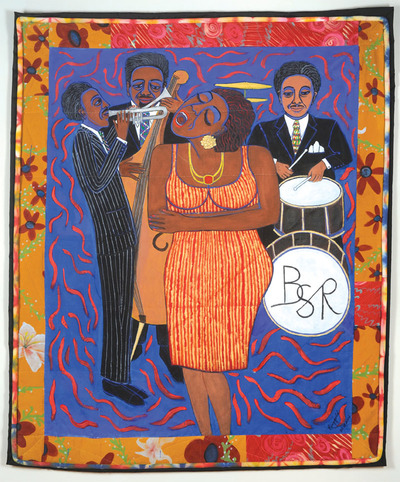

Faith Ringgold, Jazz Stories Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #4, 2004, acrylic on

canvas with pieced fabric border, 22 x 17″. On loan from ACA Gallery, NYC.

Storytelling is an important theme through much of this work. Sometimes the stories are in the work themselves and often the stories of how the work came to be are equally compelling. Faith Ringgold’s Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #4 is an example of both. A painter who pioneered the use of soft sculpture and quilt-making as fine art, Ringgold began to paint on fabric after seeing an exhibition of Tibetan thangkas in 1972. With the help of her mother, she began making quilts, often using African motifs, that told stories from her life. Ringgold marries a rich history of African American women marking important events with quilt-making and a fine art painting tradition. It also made good career sense because the works were inexpensive to ship and, as such, it was possible for more places to exhibit her work and pay her to give a talk. It was around this time that she retired from being a New York City public school teacher and began focusing solely on her artwork. Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #4 is part of a series of jazz quilts she started in 2003.

From 1915 to 1955, jazz was popular music in the United States. Its rise coincides with the move of African Americans from the rural South to urban centers in the North. Jazz clubs were one of the few places where white Americans could mix freely with black Americans. The music inspired modernism and promoted intellectual curiosity and even “free thinking.” For white people, jazz was an introduction to African Americans. For black people, jazz was the sound of a renaissance and an emerging African American consciousness. Jefferson Pinder’s epic woodcut, Musical Missionaries, entwines the black experience of slavery and oppression with the evolution of African American music from jazz to hip hop. Pinder recasts musicians as liberators.

Other artists in Convergence attempt to visually represent the ideas embodied by jazz. David C. Driskell’s Five Blue Notes is a busy, colorful encaustic and egg tempera work featuring a row of vertical bars. Swabs of paint swish and dance around the painting the way musicians riff with each other in a set. Like a visual blue note, Driskell’s marks and strokes represent the expressive techniques commonly found in jazz. Sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett is best known for her prints of African American history (Sharecropper and Malcolm X Speaks for Us) and for the statue of Louis Armstrong that stands in the large park named after the singer just outside of New Orleans’ French Quarter. In her silkscreen, Fiesta, dancers leap through ribbons as guitarists strum. Moe Brooker’s lithograph, Inside Moves, is a colorful collection of rhythmic drawing marks. The title refers to a style of free-form jazz where the players move in and out of the changes in a playful, passionate manner.

Nearly every work in Convergence is an example of how artists make visual art from music. Because that music is jazz, these works carry the extra weight of African American history and consciousness as it unfolded throughout the 20th century and continues today.

Ric Kasini Kadour is an artist and writer, reviewing Vermont’s contemporary art scene for more than ten years. His company, Kasini House, publishes Art Map Burlington and the Vermont Art Guide.

All images courtesy of Bates College.