Diversity Leads to Relevance in New England Museums

Mario Quiroz, HC 1405-FIT-FIR-0103, 2014, hand-colored black-and-white photograph, 16 x 20″. Courtesy of the Fitchburg Art Museum. Commissioned by the museum for its permanent collection.

Relevance is today’s mantra for most museums. While many won’t admit it, museums are scared to death, not of fire, flood, theft, or anything that imperils their collections as much as the threat of a long, slow drowning of the institution due to irrelevance. Museum directors’ greatest nightmare is that one day soon they will open the doors and no one will show because no one cares.

For this reason, we have entered the third era of museum history in the U.S. The first era, during the 19th century, focused on amassing collections. The second, during the 20th century, focused on educating the public. Now, 21st-century museums are defined by their quest for relevance. Everything they do is measured by how well it connects with an audience, and how it engages community support.

In the name of relevance, museums are pouring unprecedented resources into strategic planning, audience development, visitor research, programming, digitizing their collections and transforming their facilities into community spaces. Yet, dishearteningly, museum attendance continues to slip nationally. According to Reach Advisors, a leading museum research firm, the percentage of Americans visiting art museums has declined by 21% during the past few decades, and those visiting historic sites and homes has dropped by over a third. (New England museum attendance declined significantly after 9/11, but in 2014 finally climbed back to pre-2001 levels according to our visitor data tool, NEMA Stats.)

One of the leading obstacles to this quest for relevance is the lack of diversity in museum audiences, staff and boards. Many museums are dramatically out of alignment with community demographics. Minorities today make up more than a third of the population and the era of the “minority majority,” in which the multiplicity of minority groups trades places with Caucasians as the dominant group in our society, is expected in the next 20 years.

Unfortunately, museums seem unprepared for this development or unable to meet its challenges. Minority visitors are still very much minorities in our museums. Research shows that, nationwide, non-Hispanic whites make up 66% of the population, but account for almost 90% of museum visits. African Americans and Latinos, by contrast, make up a combined 30% of the population, but represent only 8% of the museum-going public.

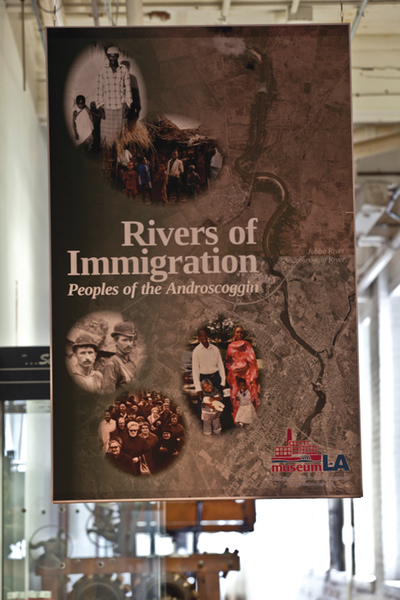

Rivers of Immigration title panel at Museum L-A, Lewiston, ME. Photo: Phyllis Graber Jensen.

Likewise, the museum profession is persistently out of step with the trend toward multiculturalism. Nationwide, 75% of all museum CEOs identify as Caucasian. In New England, the field as a whole is 90% white and 80% female. These figures don’t appear poised to change much in the near future either; in museum studies programs, which prepare the next generation of museum leadership, students are 80% white and 80% female.

Museum boards also tend to be homogeneous. According to Boardsource, nonprofit boards have made “almost nonexistent progress in recruiting ethnic and racial minorities”; more than 80% of all nonprofit board members are Caucasian. Because boards have such a strong influence on the culture of the institution, homogeneous boards tend to make the museum more insular, while diverse boards pave the way for openness.

Left unaddressed, this diversity gap points to a future museum community that is perilously irrelevant and unsustainable, unless we find ways to align ourselves with an increasingly multicultural society. There are many challenges. Researchers point out several barriers such as the feeling that museums are intimidating and exclusionary, the perception that museums are for the “elite,” and lack of museum-going and museum-supporting traditions within some racial and ethnic groups.

However, there are signs of hope. Many of our region’s museums have recalibrated their operations, programming, and, in some cases, their collections to increase multicultural appeal. Socioeconomic diversity is encouraged through programs such as the Free Fridays at 70 Massachusetts museums sponsored by the Highland Street Foundation. In 2002, the Boston Children’s Museum pioneered a program offering free or discounted admission to welfare recipients, which has been adopted subsequently by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Science; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and several others.

Participants interact with an artwork installation as part of a Free Fun Fridays event. Courtesy of the Highland Street Foundation.

Museums located in communities with rapidly changing demographics have particularly made strides to realign themselves. In Lewiston, ME, Museum L-A has been a bridge between the working-class, Caucasian community and the growing population of Somali immigrants through special exhibitions and cross-cultural events. The Fitchburg (MA) Art Museum is diversifying its outreach to Hispanic audiences through multilingual programming and exhibitions such as this summer’s Mario Quiroz: Mis Vecinos, Portraits of Fitchburg’s Latino Communities (through September 6, 2015). And the Colonial-era Shirley Eustis House in Roxbury, MA, has devised effective ways to connect its racially diverse community with a mansion built in 1747 for the English Royal Governor.

The New England Museum Association has made museum field diversity a high strategic priority. Over the past five years, we have explored the subject of diversity through conference sessions, workshops, and thought leadership. We’ve also gone beyond talking about the issue and taken tangible steps toward solutions by creating the NEMA Diversity Fund, which offers scholarships to our fall conference for multicultural community college students in order to introduce them to the possibility of working in the museum field. Our hope is to expand the fund to support outreach through high school career fairs, underwrite paid multicultural internships at museums, and support research on diversification.

If diversity efforts are to be successful, museums need to take a more active role in improving the lives of their communities by helping improve the social conditions that impact them. Museums must become advocates for their employees and audiences in the wider community, engaging in social activism and using their considerable social capital for the common good. This activism is gaining ground with museum professionals and, increasingly, museums as institutions, through social media conversations such as #MuseumsRespondToFerguson and #MuseumWorkersSpeak.

Ultimately, the quest for relevance means retooling the museum/audience relationship, as well as that of the museum/board/staff. These need to be transformed from “us and them” to just “us.” When this happens, audiences are no longer just customers, and staff members are no longer just employees. They are family. And what could be more relevant than family?

Dan Yaeger is executive director of the New England Museum Association.