Aerosol III: Graffitti’s Family Tree

A student of art history may learn that Claude Monet was a founder of the mid-19th century painting style Impressionism or that together with Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso invented Cubism. In the style of graffiti, a lover of Jean-Michel Basquiat may not know the name Lee Quiñones, a graffiti writer who made entire New York City (NYC) subway cars his canvas. Similarly, DJ NO and TESS of the NYC XMEN Crew gained notoriety years before Shepard Fairey began slapping OBEY GIANT around the RISD campus in Providence, RI. Slaps, or pre-tagged stickers displayed on public spaces, are dubbed rudimentary to some graffiti pioneers. Despite its popularity, the scholarship of graffiti is still in its early stages.

In Boston, young graffiti pupils were introduced to the burgeoning genre through Hip-Hop films such as Style Wars and Wild Style, while the 1984 book Subway Art by two photographers documented the early years of NYC’s graff movement. It was different in that within a canvas, an artist will write their name while within graffiti, their name is the art.

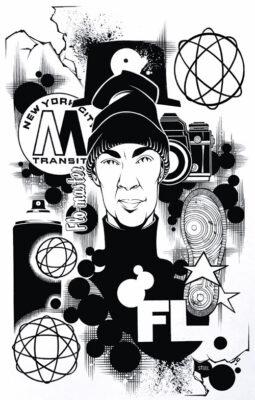

“Fab 5 Freddy was there at the beginning of American Hip-Hop and graffiti,” says artist and educator Barrington Edwards. Fred Brathwaite, or Fab 5 Freddy, was a member of the NYC graffiti crew Fabulous 5 with Quiñones and became an influential figure in bringing graffiti to the mainstream. In addition to his graffiti credits, Freddy was also a co-producer and actor in Wild Style. It was Freddy who exposed Debbie Harry of Blondie to Hip-Hop and, as a result, her “Rapture” video became the first rap song televised on the fledgling Music Television (MTV) channel. The video had cameos of Freddy and Basquiat and chronicled a slice of the city’s Hip- Hop movement which included not only rap but dance and graffiti. “It was his relationship with the art world and Blondie that skyrocketed Hip-Hop culture to a prevalence that was different from where it originated from,” says Edwards. “Which feels very American,” he adds.

Edwards is a professor at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, community activist, storyteller and together with Cagen Luse, is a co-founder of Comics in Color. He now teaches the history of graffiti as part of his syllabus on street art yet his knowledge derives from a witness account rather than studying a textbook. “We were thick in the middle of it,” says Edwards. Maurice Starr and the members of both musical groups New Edition and later New Kids on the Block (NKOTB) were regulars in the neighborhood. Jordan Knight of NKOTB went by the graffiti signature POPEYE. Gang Starr Posse featuring rap legend Keith Elam, known more widely as Guru, was also from Boston.

“These are things that we learned and we lived and we saw,” he says. Admittedly, Edwards did not become a style-master putting up burners and pieces, though his practice of drawing iterations of graffiti letters in notebooks directly informed him as an artist. “To me, that was the curriculum,” says Edwards.

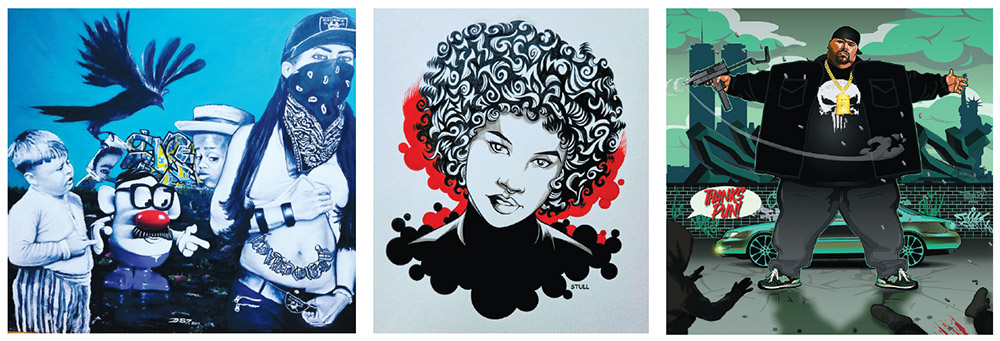

Boston-based artist Rob Stull had the fortune of traveling to New York to visit family and saw Hip-Hop’s version of graffiti early on. “I would visit New York, I would ride the elevated train lines, I would see the rooftop graffiti and I would see it in different boroughs,” says Stull. He has built an impressive resume since his days of tagging buildings. A graduate of The School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts and founder of the studio, Ink on Paper, Stull has worked as a graphic designer, curator, and comic book illustrator working for both DC and Marvel Comics.

Stull’s love of art and Hip-Hop converged when in 2000 he had the opportunity to design artwork for Guru’s Jazzmatazz, Vol. 3: Street Soul. Stull was also the first Black and first Bostonian artist to have work displayed on the banners for the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) 2020 Basquiat exhibition, Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, and, along with fellow graffiti alumni Rob “ProBlak” Gibbs, became the MFA’s first Black artists in residence. The banners were an homage to the New York graffiti artists of Stull’s youth: the late Basquiat, Lady Pink, and Futura.

Timmy “Zone” Allen is considered by many as one of Boston’s original writers in the genre. “I learned what graffiti was and what it wasn’t from people like Zone,” says Edwards. In a world where anonymity saved you from an arrest, Allen feels fortunate by the chance encounters that led him to other writers. “I just immediately hooked up with the best people,” says Allen. “Coz introduced me to Freeze,” he says. One by one, Allen would be introduced to someone who also happened to be a graffiti writer. “Click was one of the more revered writers because he had a style that was pretty impenetrable for the time,” says Allen. He lists others: Romeo, Saint, Hang, Maze. “Maze was really nasty,” he says.

Of his writing endeavors, “I don’t want to call it a career although I did get paid for it a couple of times,” says Allen. While he was coming up, Allen was a stand-alone figure, often writing his stylized name as he “beat a path home” from the clubs surrounding the Fenway neighborhood of Boston. It afforded Allen and others access to the stretch of road along the Mass Pike before it became visible to drivers. “I would always run into his tags in these weird obscure places, so when we linked up, it was kind of serendipitous,” says Stull.

Graffiti and Hip-Hop were not the only influences to young Boston artists. Stull remembers local artists Allan Rohan Crite, Dana Chandler, and Nelson Stevens also being a heavy presence in his youth. Local and legendary artist Paul Goodnight (see page 18) had an impact on Stull artistically due to his father owning several original Goodnight paintings. “Paul has been an incredible mentor and resource my entire life,” says Stull.

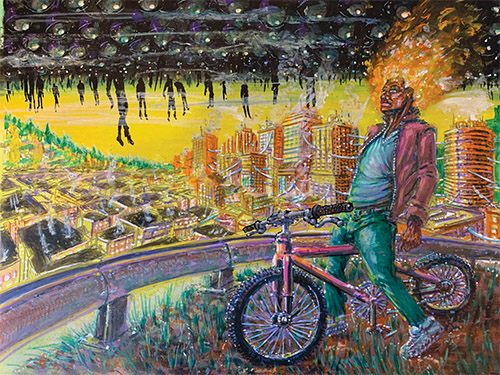

Goodnight has been a resident of Boston South End’s most of his life and has seen the neighborhood change, including its views on public art. At the time, he did not realize that the graffiti he saw on buildings and trains was a form of communication of the streets. “I didn’t know that this was a rehearsal for something bigger and better. But not just a rehearsal, they were really talking to each other,” says Goodnight. Later graffiti writer Percy Fortini-Wright translated the elements of graffiti writing to Goodnight and once he understood the lettering, meaning, and geometry, his views changed. This morph between letters and abstraction happened because graffiti writers were communicating to each other in a different language. “There was a whole language,” says Goodnight.

Goodnight represents the larger public consciousness with its ever-changing views on graffiti. To the naked eye, there is no distinction between a scribble with marker and a large scale, stylized signature. If the work is prohibited, it is deemed graffiti and thus defacement.

With the evolution of graffiti into murals and aerosol art, the attitudes and interpretations around the initial writings are now being interrogated. The understanding of the time and attention that went into these works, under the cover of night, with the threat of a felony was constructed by a compulsion to paint.

“The evolution of hand style to wild style was bringing us towards abstraction,” says Edwards. “The letters in their most abstract style, like [artist] Ramellzzee, that’s high-level conceptualization that happens at a street level without a BFA or MFA,” he says.

With educators like Edwards, current art students have the opportunity to learn of graffiti’s origin in addition to the writers ethos and code.