A Conversation with Jocelyn Chemel

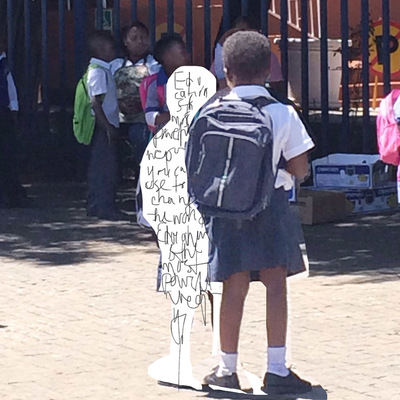

Jocelyn Chemel. School Girl. 2013. Digital photograph mounted on wood panel, resin. 12×12″. The text in the photograph is Nelson Mandela’s quote “Education is the most powerful weapon you can use to change the world”.

By Olivia J. Kiers

Jocelyn Chemel is fixated by life’s contrasts, and now she can finally speak out about them. Growing up under apartheid in South Africa, Chemel remembers that “we were all prisoners of fear.” Unable to speak freely over the phone for constant fear of arrest, Chemel left South Africa when she was 20 and is now a mixed-media artist based out of Boston. Over the intervening years, she has returned to her native country on several trips and observed it post-apartheid, but her hopes for the future are still tinged with uncertainty. Barbed, Chemel’s exhibition currently on view in Boston City Hall, explores that duality of hope and anxiety.

Following Nelson Mandela’s death in 2013, Chemel noted that a groundswell of celebration for Mandela’s legacy pervaded life in South Africa. “Mandela did the unthinkable by preventing civil war. We grew up always having our bags packed, because no one knew what might happen.” In appreciation, grateful South Africans left memorial stones painted with messages of thanks and hope outside of Mandela’s home, where Chemel took photographs that are a part of the exhibit. During this same trip, Chemel also photographed schoolchildren in Soweto, near Johannesburg. She was caught by “the contrast between these children’s pristine clothing and shoddy education.” Chemel fears that Mandela’s mission to better education is being lost under the current political climate. Her piece Schoolgirl is an altered photograph, in which a young schoolgirl is paired with “a ghost tribute to those who don’t get educated.” In a personal effort to bring the tools of creativity to those in need, Chemel has distributed art supplies to South African children in a project she calls “Art on a Mission.”

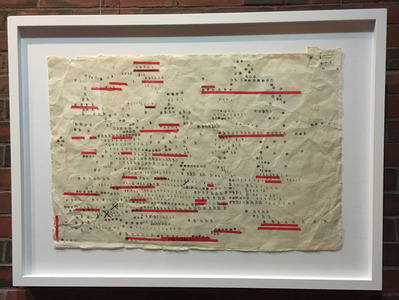

Jocelyn Chemel. Shhh. Mixed media drawing on paper, ink stamp, tape, thread. 24×36″.

Chemel’s working method is almost like a dialog, in which the handcrafted is interlaid with digital manipulation. There is a poetic justice to this; much of her work celebrates famous quotes by Mandela while also suggesting a culture of silence. “South Africa,” says Chemel, “is a country of covering up.” Barbed Pearl highlights the veneer that coats an ugly truth: coils of razor wire are covered in bright nail polish and pearls. In another powerful piece, entitled, Shhh, the sibilant word is echoed across the surface, colliding with blood red lines that mark out sections of text. The viewer is asked to literally find a “voice,” that single word floating on the peripheries of censorship.

Jocelyn Chemel. Yellow flower. 2014. Digital photograph mounted on wood panel, resin. 16×16″.

At her artist’s talk, Chemel walks from piece to piece in Barbed, elaborating on the profound importance of Mandela’s legacy for her work and for South Africa. She knits her personal memories together with the recent history and uncertain future of her country, looping the pain and hope of a particular place together like the coils of barbed wire and bursts of bright yellow flowers in Yellow Flower. Yet, Chemel insists that there is “something universal” in her tribute to Mandela that goes beyond South Africa. “I hope the world takes that consciousness [of Mandela’s message] into the future to solve problems like refugees, like militarization, and turn it into a conversation.” Looking at Yellow Flower, she sighs. “There is hope. You can see it here—nature prevails.”

Barbed is on view at the Mayor’s Neighborhood Gallery on the second floor of Boston City Hall through February 28.