About “Great and Mighty Things”

by Henry McMahon

Some of the most striking works in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s “Great and Mighty Things”: Outsider Art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection, are the sculptures of William Edmondson, who was born in 1874 to former slaves and held various manual labor jobs until his mid-50s, when a series of divine visitations—and the commandment to take up stone carving—prompted two decades of remarkably accomplished sculpting. Immediately recognizable as the subjects they depict, each of Edmondson’s carved limestone sculptures (Woman, Angel, Horse with Short Tail, Horse with Long Tail, Three Birds, and Sheep) takes form by a subtle interplay of simple planes. They are solid and believable without being overly descriptive (rough chisel marks denote the sheep’s fleece, the horses’ coats, the woman’s hair and the angel’s wings), deriving their power from a restrained economy of means.

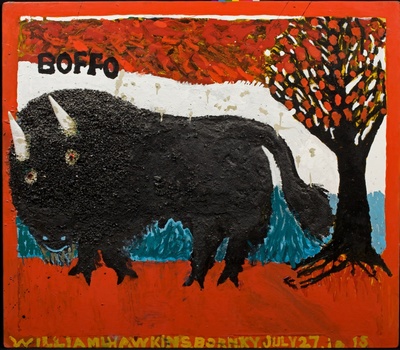

Boffo. William Hawkins, American, 1895-1990. Alkyd house paint on Masonite with fiberboard horns; textured mane and raised body made of alkyd paint mixed with broken starch chunks (possibly dried glue), 44-1/2 x 51-1/2 inches (113 x 130.8 cm). Signed along bottom: WILLIAM L HAWKINS.BORN.KY.JULY.27.1895. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection. Photography by Will Brown

Not all of the twenty-seven Outsider artists in the exhibition are of Edmondson’s quality, but enough stand out to suggest that, as a promised gift, the more than two-hundred works in the Bonovitz collection will make the Philadelphia Museum one of the top destinations for Outsider art in the country. Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz began collecting such work after viewing a watershed exhibition of African American folk art at the Corcoran Gallery in 1982, and the informative wall texts, smart-phone tour and exhibition catalogue that accompany this show suggest that scholarship and institutional acknowledgement are beginning to catch up to this hitherto underexposed genre of American art.

Walking through the exhibition, one cannot help but identify the aesthetic of much of the work on view with that of modernism, the primary “insider” art of the last century. Acknowledging the role of modernism in reinvigorating interest in the cultures from which it derived its aesthetic imperatives, we might credit it also with paving the way for institutional acceptance of those cultures. A question that lies at the heart of the Outsider genre—and of this exhibition—seems pertinent: How do we understand the motivations behind Outsider work, as different as they are from the motivations behind modernism, Outsider art’s chief aesthetic parallel?

Edmondson’s case is worth considering because, in 1937, he became the first African American to be given an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, a show of some twelve sculptures organized by the Museum’s director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Barr no doubt regarded Edmondson’s clean powerful forms as emblematic of the kinds of art that Modernism had given us fresh eyes to see. Yet Edmondson’s motivations—“I was out in the driveway with some old pieces of stone when I heard a voice telling me to pick up my tools and start to work on a tombstone. I looked up in the sky and right there in the noon daylight He hung a tombstone for me to make,”—could not have been further from the secular imperatives of the artists whose work would normally have hung on The Modern’s walls.

The most accomplished artists on view in “Great and Mighty Things”—Edmondson, Martin Ramirez (1895-1963), James Castle (1899-1977) and Bill Traylor (1853-1949)—could each be said to exemplify the modernist aesthetic, insofar as their works play with the abstract properties of simplified forms and planes. As we make associations between the look of modernist work and the work of “insiders,” we’re reminded of Ernst Gombrich, and the shared aesthetics that join all efforts at pictorial representation. This is reinforced by the subject matter of much of the work on view. Recurring motifs in this show are the very same as those that hold metaphorical power for artists of all stripes: small vessels, water pitchers, men and women, horses, dogs, sailboats, rivers and mountains.

Runaway Goat Cart, c. 1939-42. Bill Traylor, American, c. 1853-1949. Opaque watercolor and graphite on cream card, 14 x 22 inches (35.6 x 55.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection. Photography by Will Brown

Drawing with soot and spit on found pieces of cardboard, or rearranging scraps of cardboard and gluing and stitching them together into paper-doll versions of their real life counterparts, James Castle created an exquisitely beautiful visual lexicon of the everyday objects of his rural Idaho life. Born deaf yet never learning sign language, lip reading, or how to read or write, Castle seems to have turned to his work as one of his only means of communication. In the Bonovitz collection are Castle’s drawings of an overcoat and a farmhouse, and stitched-cardboard collages of a bird, a girl, a vest, a dresser, a door, a chair, sections of wall, pitchers and a bowl. Each is profoundly touching for the way its construction mimics that of its real life counterpart. Red Vest with White Buttons is constructed from a piece of cardboard folded in three to make its flaps, and adorned with five white buttons, each made of cardboard and sewn into place with a single stitch. Gray Bowl is a reused paper bag, folded into a simple bowl shape with an extra thick fold to denote its thick rim, plus white stitching to suggest a decorated surface.

Such works have tremendous aesthetic appeal, both because they reveal the fundamental abstract form of their subjects and because they show the process of their own construction. As with Barr’s enthusiasm for Edmondson, these very enthusiasms for Castle could be said to stem from an aesthetic value system bequeathed to us by modernism. As for the message of Castle’s work—that a person can become closer to the world by studying and representing his surroundings—the philosophical connection goes straight to Cézanne.

Appreciating the surprising affinities we find between Outsider works and the works of the Modernist tradition, we’re also reminded that an understanding of the latter goes only so far in helping us decipher the workings of the former. The work of Sam Doyle (1906-1985), a member of the Gullah community of South Carolina’s St. Helena Island, provides a good example. Depicting the notable people of his community (St. Helena First Black Embalmer John, Dr. Boles Hi Blood) and even their barnyard animals (Bosie and Wewe) in a loose style of bold painterly simplicity, Doyle merges figures with their grounds with a direct immediacy that could be the envy of most neo-expressionists. Emblazoning his paintings with the names of their subjects, he presents the compelling image of figures and their identities occupying the same pictorial space. That this creates an affinity between Doyle and Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose figures also share their spaces with writing and pictograms, tells us something about ourselves (and the eyes that modernism has given us) and about Basquiat’s ability to mimic the conventions of the untrained, but next to nothing about Doyle himself. Similar parallels might be made between Eddie Arning (1898-1993) and Klee, Emory Blagdon (1907-1986) and a Calder mobile, Howard Finster (1916-2001) and an Alex Katz cutout, Martin Ramirez and a Derain sketch, John Serl (1894-1993) and George Grosz, or Purvis Young (1943-2010) and Kandinsky.

Jail Was Heat. Purvis Young, American, 1943-2010. Paint on weathered Masonite with nailed-on pieces of various types of weathered scrap wood, including yellow pine and plywood, 43 x 34 inches (109.2 x 86.4 cm). Signed upper right:Young.Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection. Photography by Will Brown

Bruno Del Favero’s (1910-1995) narrative paintings of mushroom hunters and sailors present the world as a lush, mysterious realm that holds great rewards for those brave enough to explore it. They appeal for the same reason a child’s art does, yet their beautiful paint handling is animated by the very same material properties that we admire in Howard Hodgkin. That a single work can spark such polarized associations is very exciting, but it should also give us pause if we seek to connect aesthetics to any ideology. Though we might admire in Ramirez’s captivating drawings his architecture of “simple spaces,” how are we sure that such spaces were not the most complex that the artist could conceive of?

Nearly every artist on view in “Great and Mighty Things” spent a childhood in rural poverty, had little formal schooling, worked primarily manual labor, and took up art late in life. Motivated by a calling to spread their religious beliefs through their work (Felipe Benito Archuleta, Edmondson, Finster, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Elijah Pierce), by the healing properties they believed their works bestowed (Emery Blagdon, David Butler), by grief over the loss of a loved one (Emery Blagdon, S. L. Jones), or as a response to a crippling physical condition (Castle, Traylor), or an unstable mental one (Arning, Justin McCarthy, Ramirez, George Widener, Joseph Yoakum), many of them worked with a belief in the tangible forces of their creations that extends well beyond the aesthetic.

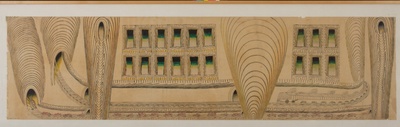

Trains, Cars, Tunnels, and Windows, 1953. Martín Ramírez, born Rincón de Velázquez, Mexico, 1895; died America, 1963. Graphite, wax, crayon, and water-based paint and ink on single sheet of paper, 23-3/4 x 90 inches (60.3 x 228.6 cm). Dated (not by artist) lower left: Mar 24-28, 1953. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection. Photography by Will Brown

Each exists outside of any tradition, and, as such, outside of the linear, progressive timeline of art history. Edmondson’s horses could be Egyptian, his birds a Brancusi, and his sheep part of the portico of a Romanesque church. His modernity isn’t due to his provenance in the twentieth- century, but to a style that twentieth-century modernists found echoes of throughout history. Just as early modernists such as the Stieglitz circle “admired the aesthetic of certain traditions (Japanese prints, African masks) from a great cultural remove, so can we admire the powerful works of the Bonovitz Collection without knowing exactly what they meant to their creators. Although modernism may have given us the eyes to discern the great aesthetic value in the works of “Great and Mighty Things,” it is the powerful draw of the inaccessible that truly animates the exhibition.

Henry McMahon is a writer and painter living in Brooklyn, New York.