Biennale Dispatch #2/2: Thoughts on the Art of the Poetic Protest

Fran Siegel

These are tense times throughout the world, and as the Venice Biennale might well be considered a form of cultural Olympics, the stakes here could be high. This is why many were surprised at the offensive tone of Danish minister of culture, Marianne Jelved, in her speech that inaugurated the provocative pavilion of artist Jesper Just. Ms. Jelved explained that walling off the front of the Danish pavilion was at odds with the mission of culture and that this work portrayed Denmark as isolationist, blocking out the outside world. Viewers were guided instead to enter the multi-roomed video work through the back.

Jesper Just- View of the former front of the Danish Pavilion

Catty-corner to the Danish pavilion is artist Sarah Sze’s contribution for the US. Triple Point is housed in the Palladian style building with its rotunda entrance blocked, so one enters the piece through the side. Sarah spoke about the importance of off-kilter gestures to destabilize the building’s traditional architecture of power. This is especially evident in the central rotunda where viewers can peer into closet-size inventory spaces, and walk around a digital rock which is weighted oddly off-center. Outside, precariously on the roof are two other teetering boulders, connected with florescent orange tape. While Sze did not violate the architecture, she revealed many previously hidden aspects of the building including a sidewall of windows that is normally concealed by a fake brick façade. So as it turns out, the building’s stable symmetry is just an illusion anyway.

Sarah Sze’s exposed window

Sarah Sze- Suspended rock on the roof

Just to the left is Israel, where a hole is dug in the floor by artist Gilad Ratmanin which corresponds to an adjacent video. Various segments of The Workshop unfold a narrative of imagined travel from Israel to Venice.

Gilad Ratmanin The Workshop

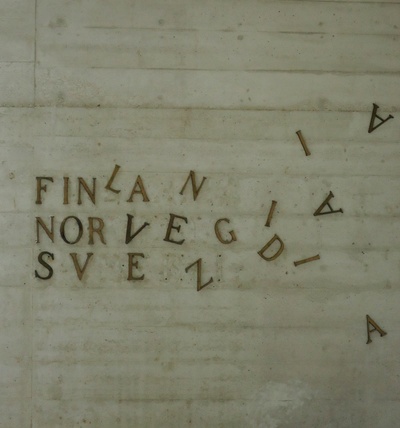

And in the vicinity is the façade of Norway, Finland, and Sweden, where the country names are scrambled.

Scrambled country names

Up the hill, the facing French and the German pavilions this year have switched. In the spirit of cooperation the artists and curators decided to follow the suggestion of the foreign affairs offices of each country. And the German contribution now housed in the former French building consists of Ai Weiwei, Romuald Kamakar, Santu Mofokeng and Dayanita Singh, none of whom are based in Germany.

Poster outside of the new German Pavilion

With a combination of low budget and high ingenuity, the Romanian pavilion remains materially empty but showcasing a fabulous performance piece by Maria Alexandra Pirici and Manuel Pelmus that reenacts the spatial organization of historic works from previous Biennales.

Romanian Pavilion performance 2013

I recall two other sparse but extraordinary installations here in former years: Dan Perjovschi’s amazing marker drawings on the floor in 1999 and Daniel Knorr’s piece in 2005 that was billed as a “counter-model to the eastern expansion of the European Union.” A thousand-page self-published reader about eastern European art was given to visitors free of charge. And if that gift wasn’t enough, subversively the back door was kept open so the people of Venice could enter the Biennale from the east through Romania—and free of charge.

From our current position of global connectivity, living in one-world where information traverses the earth in seconds, many ask if this single-state architectural construct reinforces provincial limitations. Are the pavilions themselves outmoded or would their demise make Venice resemble every other international art show?

Fran Siegel is an artist living and working in Los Angeles.