Contemporary Connections at the Currier

By Olivia J. Kiers

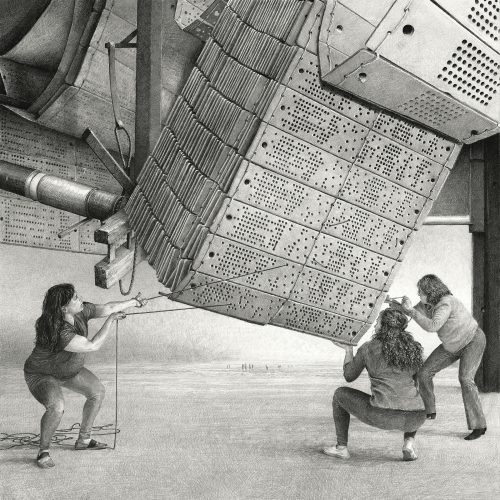

Samantha Cataldo is the assistant curator at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, NH. Cataldo recently spoke with Art New England about new developments in the Currier’s Contemporary Connections series, especially Ethan Murrow: Hauling, an installation that will feature a 100-foot-long wall drawing, large works on paper, and a kinetic “rolling drawing”—all focused on manual labor and Manchester’s industrial history.

Art New England: Let’s focus on Hauling first. How did Ethan Murrow come to the Currier’s attention?

Samantha Cataldo: We invite artists from New England to create new work for the Currier that’s based either on the Currier itself—the building, collection or history—or on our neighborhood and Manchester in general. When I first arrived at the Currier, I had a bunch of regional artists of interest that I presented to our team. One of them was Ethan Murrow.

Ethan’s hitting all the layers. He is going to involve the Currier’s building itself because he’s drawing directly on our wall… He has done tons of research into local history related to labor, and he looked in our collections and found odd objects that I didn’t even know we had. More broadly, he’s thinking about the role of an industrial city within the greater New Hampshire landscape.

ANE: What were the objects that Ethan found in the Currier’s collection?

SC: There were some things like samples of lace made in the region, or specific types of candleholders from the Industrial Era. These objects don’t go out on view as much… It was fun for me as a curator to see them, even though they won’t manifest in the finished work—they were just part of the research process.

ANE: What else makes Murrow a good fit for the Currier?

SC: He’s both an insider and an outsider in a way. He grew up in southern Vermont, with a rural upbringing. Now he’s in the Boston area. He’s a New Englander, but he wasn’t familiar with Manchester, specifically. I think that’s interesting. It’s not as if he has no preconceived notions about life in this region, but he arrived without specific knowledge…

Contemporary artists who are looking at the past really interest us. That’s a lot of what Ethan does. He’s not creating something didactic, though. He infuses his own signature style, which is nearly hyper-realistic from afar. Then, when you get up close, the hatching and contours are much more expressive. This is similar to the way he presents this historical subject matter. There is a fantastic element—moments of it that are absurd.

ANE: For a site-specific installation like Hauling, how involved are you, as a curator, in the artist’s development of the piece?

SC: Ethan is great at collaboration. There are a lot of people involved in this project, from drawing assistants who will help with the wall drawings, to several local amateur actors—Ethan does a photo shoot to get image sources as he thinks about the larger composition. Collaboration is really important to him, especially because this installation is about labor and the collaborative process. My role is to open those avenues of collaboration and communication. In general, that’s how I think of my role as a curator, when artists are creating something new. I’m a conduit to the museum.

ANE: What aspects of Hauling are most compelling to you?

SC: This project is the biggest [Ethan] has ever done, which contributes to it being about manual labor. The Sharpies that they are using [to make the wall drawing] are ultra-fine, so it’s very labor intensive.

As Americans, we romanticize being overworked. You always want to be the person who doesn’t take their vacation, who gets to the office first and leaves last. For good or bad, that’s mostly what America is like. I’m really drawn to the bigger ideas that come out of Hauling.

ANE: Do you think that Manchester residents will view this work with a different takeaway than visitors from other regions?

SC: Ethan wanted the project to end up both universal and specific. In addition to the wall drawing, there are drawings on paper, and in the middle of the gallery is a kinetic work, a 52-foot scroll we’re calling a “rolling drawing.” The works on paper deal more directly with the history of labor in this region, specifically the mills…There definitely is specificity that locals will pick up on, but his exploration of hauling—this essential act of carrying tools and the things we value—is universal.

ANE: Let’s talk more about Manchester. How do you think Manchester measures alongside other industrial or post-industrial communities in New England, in terms of engaging with the arts?

SC: I can give you broad strokes. There’s a lot that’s happening now, but I feel that we’re still at the beginning of it. There are things that are starting to work. The infrastructure is here. The mill buildings have these great loft spaces that are completely full with business and living spaces and studios… There are municipal and private groups that are working on different public art initiatives. There are also a lot of other things that help, like having new restaurants and new “third spaces,” or places where you go to hang out that are not home or work.

ANE: Are there trends or types of projects that you have seen elsewhere that you would like to see at the Currier or in Manchester?

SC: Museums are trying to be more outward-facing, placing more interactive works in public spaces and blurring boundaries between inside and outside.

In addition to Ethan’s work this fall, we’re installing The Blue Trees by Konstantin Dimopoulos. The installation is a biologically safe, water-based colorant—a vibrant blue—that is used to color trees. It’s completely safe for the trees, but it’s shocking. Konstantin started this as a response to global deforestation. The installation calls attention to this issue through installations in cities where people aren’t as concerned about deforestation, and take their landscape for granted. The blue gets you to notice the trees… We’ve commissioned the artist to do an installation that will cover parts of the Currier and also a local park near the museum, leading downtown. It’s really the first installation that we’ve done outdoors like this, publicly and beyond the museum. Like with Hauling, we’ll work with a lot of people in the community to help color the trees, which will be done by the artist with a team of volunteers, starting at the end of September.

ANE: Are there programs or initiative currently happening at the Currier that you think could be useful for other museums or communities to know about?

SC: One of the amazing things we are so proud of is called Art of Hope. It’s a gathering where families affected by the opioid epidemic can come together and basically talk about art as a tool for coping with the situation. It’s a really interesting program that’s been small and dynamic so far. It’s one good example of how a museum can use art to engage with a social and health concern, especially in New Hampshire where there’s a lot of talk going on right now about this epidemic.

The installation process for Ethan Murrow: Hauling is on view August 27–September 15. The completed exhibition opens September 15. The Blue Trees by Konstantin Dimopoulos will be installed beginning September 24 and will be complete in early October. The trees will remain blue for six to nine months, depending on the weather and type of bark.