Daisy Rockwell: The Topless Jihadi and Other Curious Birds

New Works by Daisy Rockwell

Bennington Museum, Bennington, VT

Closed December 30, 2013

By Bret Chenkin

Daisy Rockwell is primarily known as a scholar in East Asian studies, especially India. She has translated various works from the Hindi, composed reviews, and is currently at work on a novel. However, based on the prolific and quite colorful output exhibited at the Bennington Museum (although the voluminous amount of notes accompanying the show may indicate otherwise), one would have to argue that her real passion lies in painting. The show encompassed the entire hallway of the Regional Artists Gallery, with seven different subject groupings—all of which touch on feminist-socio-political themes, with no gloves on.

Rockwell’s work is mostly intimate in scale and tonally and compositionally appears to pay homage to the Mughal/Rajasthan Schools of court painting from 17th to 18th centuries. This is certainly the case with the preponderance of pastels, ornate patterns, and flattened figures. Unlike the focus on religious or courtly themes however, Rockwell’s subject is a postmodern critique of media and gender. It is also interesting to note that she paints under a takhallus or alias, the name Lapata, which means either ‘missing’ or ‘absconded’ in Urdu.

Nude 1, Acrylic, nail polish, glitter on wooden panel, 12″ x 18″

In thinking about this alias and her subject matter, which mostly treats issues of gender, the idea of ‘missing’ makes sense, for what Rockwell detects in a world in which the face of womanhood is subjected and subverted by larger, and more invidious, patriarchal forces. So, from the portrait of star witness Rachel Jeantel being bullied by George Zimmerman’s attorney, to the series honoring Whitney Houston dying in her Opheliac moment after suffering under Bobby Brown, to the Mugshot portfolio, which depicts women at the time of their arrest, her painterly gaze demonstrates the woeful state in which women still exist. In the case of Ms. Jeantel, her cudgeling under the hands of a deft and patronizing attorney resulted in her becoming immortalized as an Internet joke—but in Rockwell’s 6 by 6 inch acrylic on panel, she glowers at the viewer and is respectfully endowed with a mauve, gold, bright green, and blue coloring reminiscent of Bijapur art from the Deccan. Choti Bahu, at 8 by 10 inches, refers to a Bollywood film about a spurned wife. It shows a couple in ambiguous bliss. The Mugshots are designed to examine the rasas (Sanskrit for “essences”) of women photographed by the police. These tiny portraits have the sensibility of legendary photographer August Sander and the anthropology of 19th century-criminal document. Yet when the individual is rendered in rich vermillion, winsome greens, and aqua blues, it becomes difficult to determine the locus of their criminality. Rockwell asks us, as viewers, to determine the mood. Her coloration definitely offers interpretative clues—or maybe not. Either way, it is unusual to think of the condition of these women and some of their crimes are reprehensible. Still, Rockwell ponders, how did they get there? Are they victims as much as victimizer? The nature of their crimes—exploitative, and usually economic—may offer clues.

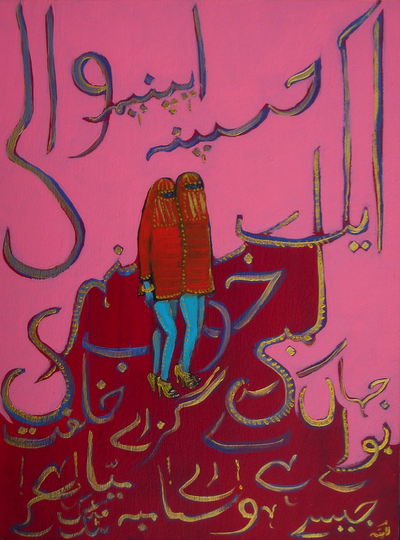

Bare-legged Niqabis, Acrylic on wooden panel, 12″ x 16″

Rockwell’s searing depiction of international womanhood makes a great companion to the watchdog media group known as Miss Representation. In this world, women of strength struggle under a drapery of traditionally female colors—as in the series Kawrage, which portrays a “self-styled Afro-Arab non-hetero-normative intellectual couch potato” living in the Middle East. Again painted in a tiny format of 5 by 5 inches, Rockwell represents Kawrage’s selfies posted online. In doing so, in the Mughal tradition, she honors this courageous woman’s postings in an increasingly misogynist space.

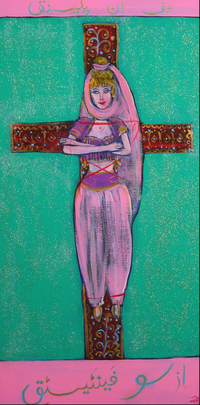

Laif in Plastiq iz so Faintaistiq, Mixed symbolism, acrylic and glitter on wooden panel, 12″ x 22″

Political Animal and Boobz take on the Byzantine machinations of Putin’s Russia from a feminized perspective. Political Animal shows Alina Kabaeva and Putin in bizarre poses based on his predilection for exhibiting masculinity in the guise of every good tyrant—with animals and a comely girlfriend. While Boobz depicts the Femen movement, the works are fraught with tension—figures are drawn in strong diagonals, and the reliance on fuchsia and lemony yellows and lime greens throw the desperate message of this movement into high relief. For example, Laif in Plastiq is so Faintaistiq, with its crucified Dream of Jeanie figure crucified, indicates how the movement lashes out at servile depictions of women in Pop culture.

Daisy Rockwell’s whole grouping is fascinating and needed in a world that continues to demean womanhood. One wonders what happens to the art without accompanying text—and one can only hope that left to speak on their own, these colorful, fascinating works insist on being properly interpreted.