For the Love of Art: Charles Weyerhaeuser and the Art Complex Museum

by Lois Tarlow

This interview with Charles Weyerhaeuser moves back in time to reveal the nature of a special family museum and its evolution to the present. It simultaneously offers an intimate view into a now-rarified art and cultural landscape.

The Art Complex Museum in Duxbury, Massachusetts, is anomalous. It is the gift of Carl and Edith Weyerhaeuser as a place to house their extensive art collections for the enjoyment of the residents of Duxbury and the public at large. The founders bought and cleared the land, and implemented the architectural design. Unlike other museums existing through the largesse of the donors, this one does not, at the insistence of the founders, bear their names on the marquee. Remarkably, a family member, their son Charles Weyerhaeuser, has been at the helm for nearly forty years. On its large rural campus the museum has become a community-minded center for regional art and the family collections, from Shaker furniture through Asian art, with formal Japanese tea ceremonies occurring regularly.

Charles Weyerhaeuser at the Art Complex Museum groundbreaking.

Lois Tarlow: The family lumber business is in the northwest, so why did your family end up on the east coast?

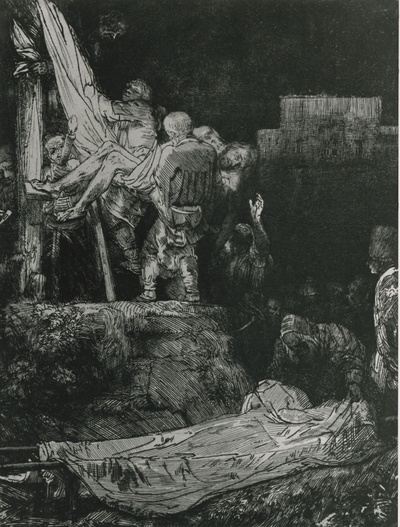

Charles Weyerhaeuser: Dad went to Harvard, where he majored in English. He loved going to the Fogg Art Museum. When he graduated, his father offered him a Packard automobile. Dad said, “No, I’d rather have the cheaper Dodge, and buy Rembrandt’s The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight. After school, it was the thing to do to go into the family business. He tried his best, surveying in the woods. He even tried banking, but he was more interested in the fine arts. The east coast had what intrigued him. He loved to write what he called fragments, sort of like haiku. Because of his love of books, I grew up with deckled edges and fine bindings. His wonderful collection is in this library.

LT: He separated himself from the business, and remained in the east with his family.

CW: Yes, but he respected what his cousins did. When the museum came about, he wanted to build a monument to wood. He used as much wood product as possible. There are pictures of huge, laminated beams arriving by truck.

When World War II started, Dad was concerned for his growing family. An uncle, a professor of Semitic languages, had passed away, and he was offered the house in Cambridge across from the Divinity School. Dad loved it. He could walk to the Fogg and attend the lectures of Paul Sachs. After the war, we moved to Riverside, Connecticut where Dad enjoyed being near New York City and the arts.

We were getting to school age, so we moved again this time to Milton to be near Milton Academy, where my mother’s sister headed the Lower School. My parents were looking for a place to relax in the summertime. Friends in Milton summered in Duxbury. They checked it out, and in 1951, purchased a real summerhouse, no insulation. In later years, my dad had accumulated a wonderful collection. My mother and her mother decided it should be shared with the public. We looked at sites on the Cape, in New Seabury, and other locations. Dad had purchased thirteen acres in Duxbury. Why not here?

Rembrandt’s The Descent from the Cross at Torchlight.

LT: What were you up to at that time?

CW: After graduating from Thayer Academy, I went to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, where I majored in graphic arts. Ture Bengtz was the admired head of the department. But I was grateful that I had sculpture with Peter Abate, and a sampling of ceramics. I was glad to have had perspective, anatomy, and design. Even though I’m not a practicing artist, I can look at a piece of art and know what went into it. I did the four-year diploma program, and then went to Tufts for the BFA.

LT: When you went to the Museum School, did you plan to be an artist?

CW: Pretty much. Then the idea for the museum came up. In ’67 and ‘68 we were working on the land. It was a jungle. A man who had worked for my grandmother was clearing it, and I came down to help him. As we burned off the excess growth, the flames nearly got out of control. It was scary.

LT: Who made the plans for the museum?

CW: Ture Bengtz made a model of what we had in mind. Richard Owen Abbott, who taught at the Museum School, was an architect. He designed the wonderful finishing curves and touches.

LT: Your mother was involved in this project.

CW: She really appreciated the arts. She had a very good friend, Evelyn Vaughn, who, at sixty, was studying at the Fogg to be our museum director, but she passed away. That was very hard. The whole thing was about to collapse, but then Ture Bengtz and his wife Lillian agreed to take on the position. We opened in June of 1971. It wasn’t right on the twenty-first, the solstice, but as close as possible. The solstice meant a great deal to Ture and Lillian Bengtz, because it was the longest day of the year. He was from the island of Aland, Finland where the winters are dark. For them, it was a complete life change. He was teaching at the Museum School, and lived in Melrose. They sold their home and move to Duxbury.

LT: There’s a lot of wood technology in the building including the famous curved roof, which echoes the nearby ocean. Was there an interaction with your family company?

CW: They had a factory in Minnesota where they constructed the beams. I’ve never been there. Dad wanted to show what could be done with wood. The siding and all the wallboards were fire treated. We learned that the beams, unlike steel, take many hours before they become a disaster. We were definitely working with the Weyerhaeuser Company.

LT: What was the collection like when Ture Bengtz took over?

CW: My dad had been collecting fine prints, seventeenth century etchings and engravings. Then he went into European and American painting. My grandfather was a businessman and put up with the arts. My grandmother loved the arts—singing and opera. She bought a house in Lenox because of Tanglewood. While living there, she got to know Amy Bess Miller who started the Shaker Colony. I think she kind of roped my father into acquiring the Shaker pieces. So we have a wonderful Shaker collection.

LT: You also have an extraordinary print collection, especially Asian prints. I know your parents traveled to Asia.

CW: Yes, that’s why we have a Japanese teahouse. Asian prints had been a constant enthusiasm with Dad. He got to know Henry Rossiter, curator of prints and Kojiro Tomita curator of Asian art, both at the MFA. My parents went to Japan with Tomita and his wife Harriet. He could get them into private collections. My mother, with her love of people, realized how important the tea ceremony was to the culture. It was her idea to import a Japanese teahouse. The house is called “Wind in the Pines,” which is very appropriate for our heritage.

Kawase Hasui, Ushibori, 1931.

LT: You have a variety of collections, among them American paintings, seventeenth century Dutch prints, textiles, Russian icons, and more.

CW: Catherine Hunter, former curator of textiles at the MFA, lived in Duxbury. She willingly did the research to produce a catalogue of Dad’s wonderful Dutch prints. Later, our curator Wendy Tarlow Kaplan did the research for the Russian icons, a major job.

LT: Unfortunately, Ture Bengtz was not the director for very long.

CW: Yes, only two and a half years. He died in November of 1973. He left a lasting legacy with the MFA and with the Boston Printmakers that he had co-founded with Otis Philbrick in 1947. In 1974, Lillian, Ture’s wife, agreed to be my associate director. She was wonderful. She had been a legal secretary, and she had the art background because of her husband. She retired in 1984.

LW: Did you continue on your own?

CW: In 1976, Lillian’s daughter, Lanci Valentine, had joined the museum as a very effective public relations director, researcher, and educator. The first curator was Peter Koernig, an artist, writer, and educator.

LT: Because of Ture Bengtz, you became a loyal supporter of the Boston Printmakers, hosting the Members Show for many years.

CW: One year we had their juried biennial. It was in connection with the Boston Public Library. Bengtz was so enthusiastic about printmakers.

Nancy Selvage, Flight Pattern, 2011.

LT: You have quite a collection of contemporary prints. Are you collecting other contemporary arts?

CW: Yes, recently we acquired a Michael Mazur painting and photographs by Robert Castagna taken on his trip to Japan. We’re definitely collecting. Because of the museum, we can live with the art for a nice period of time. Dad, when he was purchasing art, loved to have it come to the house to get a feel for how it would fit in.