Life Writ Large: Ernest Hemingway at the JFK Library and Museum

Agnes von Kurowsky and Ernest Hemingway, Milan, 1918. The Ernest Hemingway Collection; John F. Kennedy Library.

By Olivia J. Kiers

How do you distill three decades of intense activity by one of America’s most legendary writers into a single exhibition, without falling into the pitfall of oversimplifying on the one hand, or overwhelming on the other? It’s a tough task, but one that curator Stacey Bredhoff carries off to great success in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum’s special exhibition, Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars (on view through December 31). The exhibition runs chronologically, but also falls into obvious geographic zones. Thus, visitors will not only follow an outline of world events as Ernest Hemingway lived them from World War I through World War II, but they will get a taste of the author’s travels to Paris, Spain and Africa.

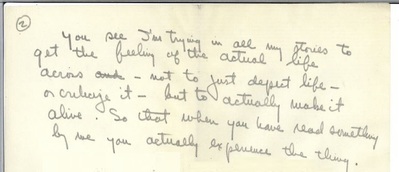

The star of this show is the written word, unsurprising because the JFK Library’s Ernest Hemingway Collection holds 90 percent of his extant manuscripts. Notable selections are on view, such as an array of variant endings to A Farewell to Arms, of which Hemingway wrote 47 different versions. Personal artifacts and enlarged photos contextualize this creative output, helping to ground some of the mythology that surrounds the life and writing of “Papa Hemingway.” Often, these objects also reveal how personal Hemingway’s writing really was. A display featuring a photo of the author with his wartime sweetheart Agnes von Kurowsky in 1918, along with von Kurowsky’s diary and a letter from close friend Bill Horne consoling Hemingway on their eventual breakup, throws the fictional narrative of A Farewell to Arms into poignant relief. “You can see the crossover of his own experiences into the writing,” says Bredhoff, who also gestures to the letter a young Hemingway wrote to his parents in 1925, containing what the exhibition calls his artistic credo: “You see I’m trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across—not to just depict life—or criticize it—but to actually make it alive. So that when you have read something by me you actually experience the thing.”

Hemingway’s artistic credo. The Ernest Hemingway Collection; John F. Kennedy Library

Left to right: Ben Fourie, Charles Thompson (obscured), Philip Percival, and Ernest Hemingway at the end of the kudu hunt, 1933/34. The Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection. John F. Kennedy Library.

Some of the items on display are simply fun to see in person. Bredhoff’s personal favorites include a drinking flask given to Hemingway by his fourth wife, and the trophy head of an impala from a 1930s safari. Other objects resurrect the ghosts of early 20th-century violence, such as Hemingway’s WWII dog tags, or his collection of “good luck charms” –a leather button, bullets, meal token, etc.—from WWI. One nice surprise is hearing Hemingway’s voice in a clip from The Spanish Earth, a pro-Spanish Republican film he narrated in 1936. Whatever their appeal, these artifacts are never far removed from the writing, and the exhibition maintains a tight focus.

From heavy handwriting to forthright stares into the camera, Ernest Hemingway’s furious energy runs through this entire exhibition. It is a must-see, not just for those interested in American literature, but for anyone who wants to explore the workings of a creative mind living through the tumult of history.