Pain(t)ed Justice: The Curious, Troubling Case of Portrait of Wally

Pain(t)ed Justice: The Curious, Troubling Case of Portrait of Wally

by Ethan Gilsdorf

Egon Schiele’s “Portrait of Wally” (1912)

Courtesy of The Leopold Museum

The trials and tribulations surrounding Portrait of Wally are by now largely known in the art world. A famous Egon Schiele painting, stolen by the Nazis and “misplaced” in a famous museum’s collection, gets unearthed and justice is restored. A new documentary, which bears the same name as Schiele’s coveted 1912 painting, is the first effort fully to connect the controversy’s many sub-plots and dead ends. Andrew Shea’s Portrait details the controversy, and subterfuge, surrounding the painting that, as the film’s tagline hyperbolically claims, was the “The Face That Launched a Thousand Lawsuits.” Well, not a thousand. But several.

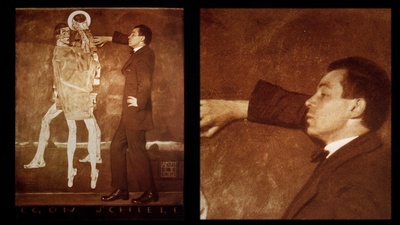

To recap the backstory: Female nudes were Austrian painter Schiele’s favorite subject matter, and his work grew more and more erotic over his truncated career (he died at age twenty-eight). Portrait of Wally [Bildnis Wally Neuzil] was one of Schiele’s more traditional works, a portrait of his mistress and model Walburga (“Wally”) Neuzil. The painting, a closely cropped head shot, ended up in Vienna’s Leopold Museum. But of course, that is not the full story.

As the film shows in an exhaustive and sometimes over-dramatic display of detail, Portrait of Wally first belonged to Lea Bondi, a Jewish art dealer who fled Austria during the war. The painting was taken in 1939, when an Austrian collaborator and art dealer seized her collection. Wally was later liberated by the U.S. Army, or rather, it was lost. The painting did not return to Lea Bondi. Due to a Post-War clerical error, and other convoluted circumstances, in 1954 the painting was eventually bought by a collector, a Schiele fanatic named Rudolf Leopold. When his collection of some 5,000 works of art was purchased by the Austrian Government to found the Leopold Museum (of which Leopold was made director for life), Portrait of Wally joined other Schieles on its walls.

It turns out that Leopold had misled or lied to Lea Bondi. He had promised to help her find the missing painting, and later, covering his tracks, he whitewashed the fact that Bondi was its true owner. Bondi eventually discovered that Leopold had purchased Wally for himself, but she died in 1969. By 1972, Leopold’s sneaky accounting had deleted Bondi’s name from the painting’s provenance. When the painting traveled in 1997 to The Museum of Modern Art as part of a Schiele retrospective, the New York Times journalist Judith H. Dobrzynski undertook extensive investigative work to reveal the painting’s true history.

Andrew Shea, Still from Portrait of Wally, 2012.

Bondi’s heirs then sued, issuing a subpoena to prevent the return of Wally to Austria when the show ended. The Manhattan District Attorney and the U.S. Government got involved on the side of the Bondi heirs. The U.S. Customs Service seized the painting. MoMA dug in its heels, siding with Leopold. Another Schiele collector, Ronald Lauder (heir to the Estée Lauder Companies fortune), happened to be chairman of MoMA and, paradoxically, founder of the Commission for Art Recovery, which returned Nazi loot to Jewish families. (Lauder was also U.S. ambassador to Austria in the Reagan Administration, a fact the film overlooks.) Lauder took the museum’s side, as did most of the county’s major art institutions, including Boston’s MFA and even New York City’s Jewish Museum, citing concerns that museums everywhere would be afraid to lend works if the Bondi suit should prevail in court.

Leopold died in 2010, just before the climax of the thirteen-year court battle, which ended with the Leopold Museum paying $19 million to Bondi’s heirs, thus ending one of the most famous cases of Nazi plunder and art restitution.

Despite its honorable intentions, Portrait of Wally the documentary isn’t all triumph. For one, there’s an uncomfortably frenetic air to director Andrew Shea’s touch. Shea, whose previous films were the thriller Forfeit (2007) and the drama The Corndog Man (1999), packs in more than thirty talking heads —everyone from art critics to Bondi heirs to federal agents and journalists (including, inexplicably, Morley Safer), shot from oblique angles and in unnecessary close up. The director also tarts up archival stills with dizzy camera movements, and he pipes in sound effects over silent black-and-white footage. More glaring is the use of hand-held camerawork to reenact the looting of Bondi’s gallery. Perhaps Shea worried the story itself would bore the reader without such enhancements? At ninety minutes, perhaps the documentary is one reel too long.

Still from Portrait of Wally, 2012.

From the perils of do-gooding to the sketchy ethics of running a museum, Portrait of Wally raises smart questions, but Shea leaves many unexamined. For me, the true story is less about the court case and more about Rudolf Leopold— what he knew, and when, and why he forged the provenance. We see footage of his deposition, and his wife’s version of events, but any effort to uncover his motivations, and illuminate his dark heart, is missed. The other curious rabbit hole left unexplored is the case of David D’Arcy, one of the interviewees, a reporter who was fired by National Public Radio for an alleged error in his radio report about the MoMA kerfuffle. (In the film, both NPR and MoMA refused to comment.) Funny that D’Arcy is also credited as the film’s co-producer and co-screenwriter, yet there is no mention in Portrait of Wally that, in 2006, D’Arcy charged NPR and MoMA in a $5 million slander and wrongful termination suit. Can you be both a plaintiff and a documentary filmmaker?

Many of the talking heads, including the Bondi heirs, repeat that the restitution was never about the money, it was about the principle. One of the “last prisoners of war” was returned, they say. The battle over Wally ultimately was about history and truth. Yet there’s this final, unexplained irony. Yes, the heirs got a huge paycheck, and the painting is now shown accompanied by a text recounting its true twisted tale. But the Bondi heirs agreed to forfeit any future claim to Portrait of Wally. And the enemy, the Leopold Museum, now owns the painting. To my mind, a fat payoff does not equal justice.

Anonymous, Egon Schiele, 1914.

Journalist, memoirist, critic, poet, teacher and geek Ethan Gilsdorf, the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks, contributes to the New York Times, New York Times Magazine, Wired, Boston Globe, wired.com, and Salon.com. Read more at www.ethangilsdorf.com.