Robert Freeman’s New Works

Robert Freeman, The Sundowners, triptych. Photo credit: David Leifer Photography.

By Olivia J. Kiers

Robert Freeman’s New Works at Adelson Galleries in Boston (through January 29, 2017) presents a world as exuberant and mythic as the painter’s process itself. A respected artist and former arts educator at Harvard University and Noble and Greenough School in Dedham, MA, Freeman has filled Adelson Galleries with his bold works. Earth tones harmonize with brilliant sky blues, reds, kelly greens and gold leaf. Out of it all, figures emerge, standing stately in evening attire, playing instruments, faces staring out at the viewer in dynamic compositions. Several works, like Ashanti Gold and The Sundowners, are life-size triptychs or diptychs.

Freeman’s subject matter follows his own background in middle-class African-American culture, drawing from years spent growing up between Ghana and U.S. boarding schools, but for him, style and process are equally important. The central canvas in The Sundowners was created from a reference photograph of his parents in the late 1940s, yet this painting is an outlier in the show. Usually, when he begins a canvas, Freeman will “just start to scribble” with black and white paint across the blank canvas until arms and legs begin to appear. It’s a process he has been honing his entire life, as he explained in an interview with Art New England. “I used to scribble and make up stories when I was about 6 and 7 years old, on blank pieces of paper for hours at a time, to a point when the paper got completely black. It’s a little strange, and my parents thought it was strange because it didn’t look like art to them. Even I’m not sure it was art as much as it was storytelling, just going off into another world.” Freeman still equates his process with writing. “That kind of black and white power—that’s what I do it for, just to move the paint around. Then I decide who these characters are, I think in much the same way as characters come to writers.”

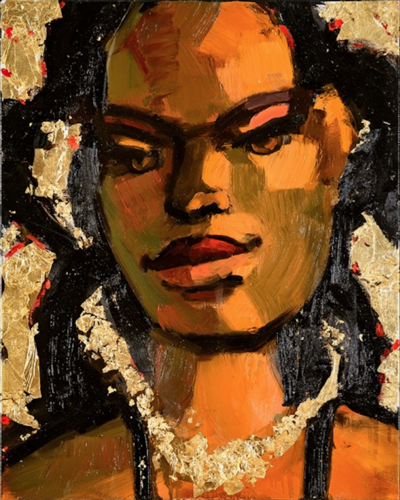

Robert Freeman, Golden Necklace 8. Photo credit: David Leifer Photography.

There’s a long list of artists Freeman looks to, from his African American mentors from his time as a student at Howard University and Boston University—Lois Jones, Richard Yarde and John Wilson—to Expressionists from both sides of the Atlantic—Max Beckmann, Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline. In terms of cultural influences, his paintings include references to his parents’ African art collection and to the elegant world of 20th-century evening wear. The gold leaf so prominent in the Golden Necklace series draws not just from African-American street culture, but African symbolism that links gold to warmth and wisdom as well as wealth.

There is something beyond both the cultural and personal backstory and Freeman’s fascinating use of “scribbling” that possesses the viewer of New Works. While his works are secular, there is something of the sacred icon in many of them, especially the Golden Necklace series, so full of gazes that appear to be confidently guarding some secret. The figures are ageless—brimming with youthful energy and inhabiting bodies that are almost too perfect. Freeman states that his canvases “are incomplete without someone viewing them, because they are looking right out at the viewer.” The first clause of that statement could really apply to any work of art. Yet not every work of art looks back with such intensity, commanding the viewer’s gaze like Freeman’s do, and in such an ambivalent way. “These works really leave it up to the viewer to see or to feel whether they are being accepted into the group or rejected by the group,” he explains.

On the exhibition’s opening night at Adelson, the gallery was filled with people just as intent on mingling as they were on viewing the art. In this atmosphere, it was easy to connect with the activity in Freeman’s paintings. It was as if the parties portrayed on canvas had come to life and overflowed into reality. Given the looming space of a quieter Adelson Gallery, they will surely affect the viewer in a different way. It is not that these paintings are overcome too easily by their environment. Rather, they are strong enough to hold multiple meanings, to be both welcoming and maintain a distance, to remain fresh and to hold the viewer captive in long consideration.