“The Odyssey Project: An Old Story for Modern Times” at the University of New Hampshire Museum of Art

By Emily R. Bass

What can we learn about life today from an epic about monsters and gods, ancient conquests and a 20-year journey by boat? This was the question posed in The Odyssey Project: An Old Story for Modern Times, on view at the University of New Hampshire Museum of Art through December 14.

The Odyssey Project is the first-ever group exhibition curated by a long-running artist-run book club, who found inspiration in Emily Wilson’s contemporary translation of The Odyssey.

The 25-year-old book club is made up of 15 New England-based female artists, as well as one longtime member who passed away last year, Jenifer Gordon Mumford: Nancy Berlin, Ruth Fields, Carol Greenwood, Jane Kamine, Colleen Kiely, Marilyn Levin, Jennifer Moses, Karen Moss, Sterling Mulbry, Carla Munsat, Ellen Rich, Judy Riola, Civia Rosenberg, Sandra Stark and Brenda Star.

The group is connected by gender and profession, yet diverse in perspective and viewpoint. Since its founding, the club has aspired to organize an exhibition or collaborative art project, and when Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey came out in 2017, the group knew straight away: This was the chance.

Wilson’s is the first English translation of the poem by a woman, a point of view that graces each page of the book with accessibility and approachability. Whereas past translations were written by and for academics, Wilson rejects elevated, exclusive language. Her writing includes women, both in word choice and treatment of characters; Instead of calling the slave women Odysseus encounters “whores” or “creatures,” a typical find in past translations, Wilson simply calls them “girls,” granting them the respect past translators have denied them.

Wilson’s The Odyssey points a mirror inwards, self-consciously drawing attention to the underlying structures this classic tale is built upon: hierarchies of power, gender and class that are as prevalent today as they were in Homer’s time. “The story is timeless, not timely,” The Odyssey Project artist Carol Greenwood explains. The themes in the poem speak volumes to contemporary dilemmas: migration and the (im)possibility of coming home, war and violence, the importance of family, and time’s effect on relationships and personal identity. Like a roundtable discussion in a book club, this exhibition’s strength comes from the differing perspectives brought into conversation with one another. While each artist’s work shows highly personal reflections, the exhibition reveals threads of similar themes.

Although working in different media and styles, Carla Munsat (co-founder of Art New England) and Carol Greenwood examine Penelope and Odysseus’s relationship from similar viewpoints. Each is concerned with the lapse of time that passes during Odysseus’s journey, reflecting on the effect that has on both individuals in the relationship—both the away and the awaiting.

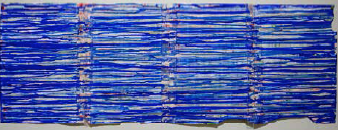

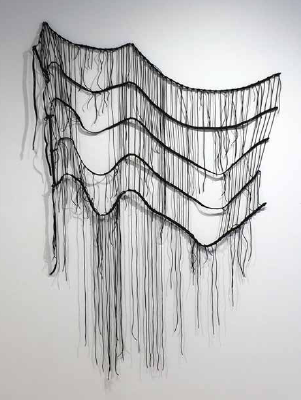

For 20 years while her husband is at sea, Penelope wards off eager suitors by promising she’ll choose a new husband as soon as she finishes weaving Odysseus’s father a shroud. But at the end of each day, Penelope unravels all the weaving she’s completed. Munsat’s Penelope’s Trick reflects the strain those 20 years had on her. Made from a repurposed leather blanket used to protect a horse from flies, the work evokes the physical wear and tear of Penelope’s woven shroud, its thin strands curling and breaking off from handling over time. “[Penelope] experiences her attachment as the destruction of her self,” writes Wilson. Penelope cannot control her situation, cannot bring her husband back from war with pure will. She can only exert control over a material for so long before it snaps and disintegrates.

Greenwood similarly looks at the relationship of Penelope and Odysseus in her visual poem, re:union. In The Odyssey, Penelope tests Odysseus to make sure the man before her is truly her husband by asking him to move their bedframe. Odysseus reminds her that their bed is built around a large olive tree, rendering it immovable. Greenwood (who once took a drawing class based on The Odyssey during her studies at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts), revisited the symbol of the tree as the foundation for Penelope and Odysseus’s marriage. Her found object sculpture alludes to the “tenuous and sometimes surprising” elements of a long-term relationship, blurring the lines between deeply rooted and finely balanced, kept together by circumstance yet easily toppled over with the slightest disturbance. The simple materials and visual composition of re:union allow the viewer to see their own experiences and ask: “What, if anything, remains unchanged over time?”

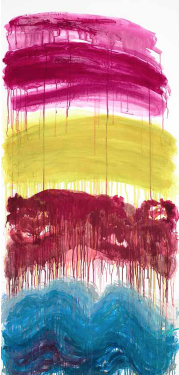

The trials and tribulations of Odysseus’s journey prompted personal and political reflections from artists Jennifer Moses, Jane Kamine and Sterling Mulbry. Kamine began her painting Wine, Oil, Blood and Water with a personal reflection on the bodies of water she’s lived along in her lifetime, at times living upon the Atlantic and Pacific, the Mississippi and the Hudson, and now, the Charles. In The Odyssey, “The Mediterranean becomes a protagonist often used by the Gods as Odysseus’s adversary and eventual savior as it carries him to war and eventually home,” she says. What began with a meditation on water turned Kamine’s focus towards the other liquids that carry the story along: blood as a symbol of both life and death; oil used to clean and heal wounded, weary bodies; wine as a marker of status and a symbol of hospitality offered to visitors. Each pigment Kamine lays on the canvas flows into the next, gravity pulling the paint downward. The movement in the piece implies a journey like Odysseus’s—slow and full of unfolding meaning.

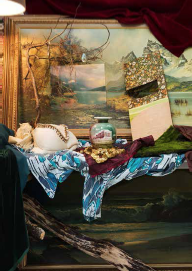

Moses’s mixed-media wall collage Across The Sea of Years captures the many layers of chaos and turbulence Odysseus faced in his journey. An anthropomorphic contortion stumbles into the composition, its Matisse-like rounded body on the verge of being sucked into the sea forever. Moses’s collages consist of imagery personal to her: a yellow pattern taken from a decorative fresco in Italy, which borders the collaged blue mass like a sandy shore just out of reach; rough terrain photographed at Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico, rocky like the obstacles Odysseus faced; and pieces of other drawings and paintings from Moses’s own work. Through these personal relics, Moses connects her journeys in life—as a painter and as a traveler—to the fabled trip of Odysseus.

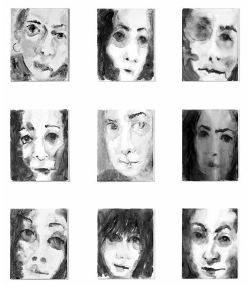

In her series of paintings on torn rag paper, Mulbry draws a parallel between Odysseus’s longing for home and recent conversations about migration. Throughout the poem, birds—“frequent migrants themselves”—are depicted as a stand-in for the human condition. Mulbry’s intimate portraits of birds give a “face” to the issue of immigration. “Daily, worldwide media streams stories of the migration of refugees fleeing for their lives, their search for their loved ones, and too often their deaths,” she says. The torn rag paper the birds are painted on feels like a relic, like a precious fresco removed from a wall for preservation, a small memorial to lives lost at sea or washed up on shore. By painting portrait homages to these migrants, Mulbry promises that these lives lost at sea will not be forgotten.

The Odyssey Project: An Old Story for Modern Times celebrates similarity and difference. The exhibition is a conglomerate effort, a coming-together of different disciplines, backgrounds and perspectives. In addition to their artworks, the artists invited the UNH community to share their own responses to Wilson’s translation. The theater, music and dance departments created cross-discipline collaborations inspired by the book. Wilson’s translation served as the source for the theater department’s own production of The Odyssey. Over the past several weeks since the opening, many classes at the university have also made their way through the galleries, connecting their writing to geography curriculums to the artworks on display.

“Political milieu today is that people break down into little categories,” says Greenwood. The artists in The Odyssey Project, operating in stark contrast to these divided communities, prefer to see all the parts as a whole, “an all-encompassing society.”