Who, What, When, Where?

By Martha Buskirk

Book reviews of Ming Tiampo’s Gutai: Decentering Modernism (University of Chicago Press, 2011) and Judith Rodenbeck’s Radical Prototypes: Allan Kaprow and the Invention of Happenings (MIT Press, 2011)

How is it that certain examples come to stand as shorthand markers for an artist’s work, or even an entire movement? The first gambit in any such reassessment is likely to involve proffering an alternate slate on which to build the analysis. For event-based work there is the further challenge of sifting through the traces, documents, and residue relating to manifestations that remain tantalizingly beyond any opportunity for direct experience.

Left: Judith Rodenbeck’s Radical Prototypes: Allan Kaprow and the Invention of Happenings (MIT Press, 2011) Right: Ming Tiampo’s Gutai: Decentering Modernism (University of Chicago Press, 2011)

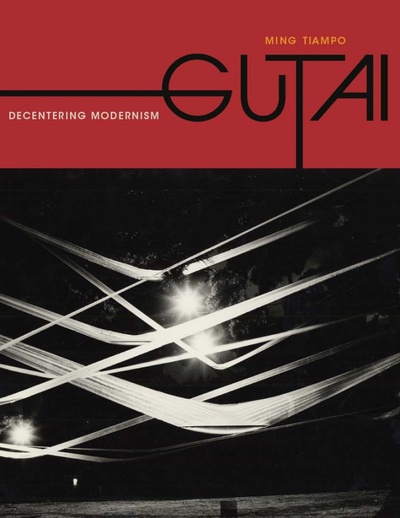

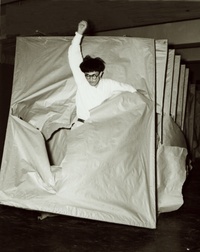

The Gutai group, operating in postwar Japan, is frequently represented through a set of iconic images from the late fifties, including Kazuo Shiraga’s Challenging the Mud, Saburō Murakami’s Passing Through, or Atsuka Tanaka’s Electric Dress, that emphasize the element of performance in their early event-based actions. But far less attention has been paid to Gutai’s 1960 International Sky Festival, despite the fact that their practical solution to presenting an international exhibition also involved a questioning of the artist’s hand that anticipated later conceptual strategies. Artists from Japan, the United States, and Europe were represented by designs submitted as small-scale sketches and then translated by members of the Osaka-based group into banners that appeared, over the course of six days, suspended by balloons above the Takashimaya department store in Osaka.

Kazuo Shiraga’s Challenging the Mud, Saburō Murakami’s Passing Through

Atsuka Tanaka’s Electric Dress

Nor has Allan Kaprow’s 1961 A Spring Happening generally come to the fore in discussions of his work from this period. Enclosed in a claustrophobic space, the audience was surrounded by activities that could only be viewed through narrow slits, while subjected to a cacophony of sounds from an electric saw and the beating of empty oil drums directly over their heads. The audience was then scattered by the sudden onslaught of a man with a flashlight pushing a gas-powered lawn mower into their midst just as the hinged walls of the enclosure fell open to release them. Yet this work was also transitional in certain key respects,incorporating direct provocation while nonetheless holding onto a distinction between audience and action (at least until the final moments) that was not fully satisfying even to Kaprow himself. (1)

On the face of it these two manifestations could not be more divergent: collective authorship and individual, kite-like banners calmly floating in the sky versus a dark and threatening enclosure, with these events proffered to audiences on opposite sides of the globe. Yet the links between Kaprow and the Gutai artists are equally compelling, encompassing not only an emphasis on event but also reciprocal knowledge, as well as a shared point of origin in their responses to abstract expressionist painting. Each has been the subject of a major museum survey that has drawn renewed attention to their achievements. (2) But where ephemeral work is concerned, it is important to recognize the role of independent scholarship, not beholden to a specific exhibition program. Ming Tiampo’s Gutai: Decentering Modernism (University of Chicago Press, 2011) and Judith Rodenbeck’s Radical Prototypes: Allan Kaprow and the Invention of Happenings (MIT Press, 2011) both offer thoughtful reassessments that situate their event-based work as part of a larger historical account.

While it would be difficult to scan the twentieth century without acquiring at least a glancing knowledge of the Gutai artists in Japan and Kaprow in the United States, the more challenging question concerns how their achievements have been written into this narrative. Founded in 1954 by Jirō Yoshihara, a painter and wealthy industrialist, Gutai has earned pride of place early in the history of postwar experimentation for a rereading of Jackson Pollock’s work according to “concrete” principles realized through an engagement with performance and materials. In the standard thumbnail portrait Gutai emerges early, but also flames out quickly, due to a misdirected (and retrograde) return to the painted object encouraged by French critic Michel Tapié. (3) Kaprow enters the history a bit later, yet the idea of a progressive development during the second half of the 1950s and into the 1960s, as he moved from assemblage into the large-scale environments and increasingly open-ended happenings, has helped to assure his ongoing historical relevance.

Tiampo and Judith Rodenbeck complicate the picture in interesting ways. Both authors approach their subjects through a broad contextual analysis, looking at questions of influence and reception. For Tiampo, one of the necessary frames concerns unequal readings of inspiration adhering to the circulation of European modernism in Japan and the dissemination of Japanese work in the United States and Europe. This process of navigation, and negotiation, is a continuing subtext in relation to Gutai’s attempts to engage the wider art world, both through exhibitions and through publications that functioned as alternate spaces for display. Tiampo’s subtitle, “decentering modernism,” refers both to efforts to participate in a discourse while operating from the periphery, and to larger questions about originality claims themselves. Kaprow’s experimental work also pushed against boundaries concerning art’s definition, but with the crucial difference that he was doing so from within a postwar cultural center. Responding to his diametrically opposed position – on the inside, looking out – Rodenbeck situates the happenings as a response or counterpoint to both painting and theater, within a wider avant-garde frame that includes John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s exploration of events as well as readings of the city, commerce, technology, and time itself.

Some of Rodenbeck’s most important insights concern relationships between happenings and theater, as she counteracts Michael Fried’s dismissal of the theatrical, along with a standard reading of happenings as antitheatrical, with a more nuanced understanding of the interchange between avant-garde theater and art in this context. Regarding the participants in the happenings, Kaprow emphasized tasks rather than roles, a distinction that Rodenbeck considers in relation to performative qualities that stand in contrast to the “unhappy performative” found by J. L. Austin in more traditional drama. Yet even though Kaprow saw his happenings as set off from the experimental work of Judith Malina and Julian Beck’s Living Theater based on the difference between “acting” and “doing,” that did not prevent him from relying on some of the actors from the Living Theater’s contemporaneous play The Connection to perform the actions in his 18 Happenings in 6 Parts. Rodenbeck also traces the impact of Antonin Artaud’s Theater and its Double in this context, via the translation begun by Mary Caroline Richards at Black Mountain in 1952, which was disseminated through various readings prior to its publication in 1958— drawing associations between Living Theater productions and the confrontation evident in Kaprow’s Spring Happening, as well as emphasizing the impact of Cage’s selective reading of Artaud’s treatise.

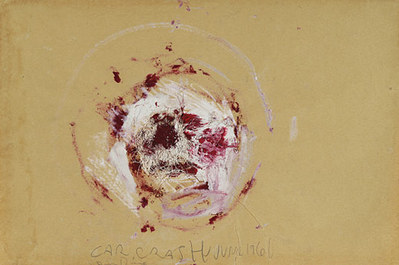

Jim Dine’s Car Crash #1

Jim Dine’s Smiling Workman

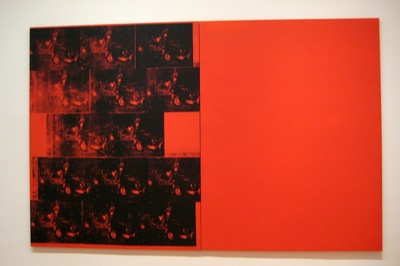

Again and again in this history, however, one also encounters the long shadow cast by abstract expressionism. For Beck, who stopped painting in favor of the “social art” of the theater, both abstract expressionism and the happenings were important for the Living Theater’s development. In the New York context, the relationship to painting was evident not only in Kaprow’s extended response to Pollock, but also in the work of Jim Dine, who remained tied to the medium despite such notable happenings as his 1960 Car Crash and Smiling Workman. Rodenbeck describes these happenings as “painter’s theater,” in contrast both to more traditional theater and to later performance art. In Rodenbeck’s thoughtful consideration, Dine’s overlay of humor and cruelty opens onto an analysis of how the “speed, intensity, and blackout structure” of his happenings relates as much to image making practices as to theater (180). Nor does she stop there, since she also interrogates the events as a way of acting out trauma, including Dine’s own and the famously fatal crashes of Pollock and James Dean. She draws connections to thematically related examples (Andy Warhol’s car crash imagery or Arman’s 1963 White Orchid), while never losing sight of the impact of Robert McElroy’s iconic images of the event on this ongoing process of historicization.

Andy Warhol’s Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times

Arman’s White Orchid

Pollock was likewise crucial for the Gutai artists as they looked for a path out of the emphasis on mass allegiance during the war years, positing what author Tiampo characterizes as “radical individualism” as a counterpoint to totalitarianism (40-41). In that context, Pollock provided a paradoxical springboard, not for a break not with painting itself, but with a Euro-American conception of modernism, based on Gutai’s attempts to extend painting’s engagement with space and time. In fact both authors cite the notion of creative misreading explored in Harold Bloom’s 1973 Anxiety of Influence—Rodenbeck in reference to Cage’s version of Artaud, and Tiampo more centrally, as a means of articulating how Pollock was pivotal for work that turned much more fully toward materials and process.

Yet the stakes were very different in these two settings. As Kaprow articulated his relationship to Pollock as part of his embrace of the everyday, he was nonetheless operating within the avant-garde center of his moment, in dialogue with “a core group composed of artists, writers, musicians, and fellow travelers” (120). The art world inhabited by Kaprow was thus at once far-reaching and insular, with its multiple forms of avant-garde exploration constantly intersecting, but also playing to a relatively limited range of regulars. Gutai, by contrast, was not only distant from American and European centers of gravity, but was actually operating at a double remove, since even within Japan they were based in the more peripheral city of Osaka, rather than Tokyo.

For Gutai, the intersection of painting and event was both central to their identity and the source of ongoing problems of how to situate the movement. Paintings created by Kazuo Shiraga with his feet or by Akira Kanayama using a toy car moving around the canvas were evidently of a completely different order than the modernist work that provided a jumping-off point. But in relation to the desire to operate on an international stage, Tiampo argues, both resemblance and contrast were equally freighted. After all, close identification risked being dismissed nothing more than imitation of dominant trends, and a divergence that was too great might fail even to register as part of the extended dialogue.

In relation to ongoing attempts to reach out to different segments of the international art world, the connection forged with Michel Tapié was clearly a mixed blessing at best. Yoshihara was certainly enticed by Tapié’s international connections, but in Tiampo’s telling of it the reciprocal motivation was equally significant, as Tapié latched onto Gutai to help shore up the relevance of the art informel that he was continuing to champion. And for Gutai his backing was ultimately more destructive than beneficial, given that his framing of the work as a form of contemporary Zen painting made Gutai seem strikingly out of step with avant-garde developments that they had actually anticipated. The consequences of this rearguard strategy were fully evident in the critical failure of their New York debut at the Martha Jackson Gallery in 1958.

The 1960 International Sky Festival is just one of the examples marshaled by Tiampo for a narrative that continues well beyond the early experimentation and the 1958 fiasco. A reciprocal engagement between Gutai and Ray Johnson, based on their mutual interest in exploring multiple avenues of dissemination, opens onto a consideration of how their activation of mail art can also be read as an extension of a Japanese tradition of hand-made new year’s cards. Less expected is one of the other ways they came up with to disseminate the cards via a vending-machine-type display in a 1962 exhibition that allowed viewers to deposit a coin and receive an example—without apparently realizing that the process was only marginally mechanical, since inside the box was one of the artists, actively choosing which card to give to each customer. Tiampo recounts how the group managed a much stronger representation of its achievements in the 1965 Nul exhibition in Amsterdam. Although Yoshihara showed up, to the organizer’s surprise and dismay, with luggage filled with rolled canvases, the Gutai artists managed to redirect their efforts. They offered reconstructions of a series of historical works from 1955-57 that served the double purpose of helping to break the informel connection and also showng Gutai as early (rather than derivative) participants in the history highlighted by the exhibition.

One important thread in both of these recent studies is the importance of multiple means of dissemination. The books and contemporary periodicals in Yoshihara’s library were critical for Gutai’s engagement with European and American developments, and Gutai was intent on reversing the movement as well through the dissemination of their own magazine. Evidence of their success was suggested by the discovery of issues 2 and 3 of the journal among the effects in Pollock’s studio after his death. The 1956 One Day Only Outdoor Art Exhibition that was actually staged just for journalists failed to yield up a feature in Life that would have delivered information about their achievement through the same relay that had brought them news of Pollock. But they were much better served by a 1957 article in the New York Times that presented a substantial discussion of work from several of their exhibitions, and brought their work to Kaprow’s attention prior to his 1959 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (as Tiampo is quick to point out). For the Gutai artists, the magazine as alternative exhibition space was therefore crucial, with work disseminated through their own journal (often accompanied by texts in English as well as Japanese) and other publications.

Rodenbeck recounts how Kaprow was critical of photographic documentation, both for the problem of how an experience could be conveyed through a flat, still image and the influence on the event itself, provoking participants to act self-consciously for the camera. Yet despite his concern about the disruptive role of documentation in relation to the happenings, Kaprow was also clearly aware of the importance of such records, as well as the advantages of shaping their context: his 1966 Assemblage, Environments and Happenings provided a major venue for disseminating his own early work as well as establishing it within an international framework. This was one that did indeed include Gutai events.

Context is everything: this is the inescapable conclusion drawn from both of these books. Rodenbeck threads her way through a convergence of forces that is at once concentrated and far reaching. She proves, as much by demonstration as direct argument, the futility of trying to understand the significance of happenings without viewing them in relation to intertwined developments across the arts (painting, music and dance particularly), with these cultural developments likewise inseparable from urban and commercial forces. The challenge Tiampo sets for herself is equally significant, as she presents a sustained body of new research extending across Gutai’s entire period of activity that also situates their specific achievements in relation to a complex interplay of influence and reception taking place on an increasingly global stage. At a pivotal moment, artists acting both individually and collectively were responding to the fading dominance of modernist painting. They did so through an open-ended engagement with materials and situations that continues to reverberate, despite the haunting distance that has opened up between the initial events and their later historical audience.

Martha Buskirk is Professor of art history and criticism at Montserrat College of Art in Beverly, Massachusetts, where she has taught since 1994. Her most recent book, Creative Enterprise: Contemporary Art between Museum and Marketplace, was published by the Continuum imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing in 2012.

1. On Kaprow’s ultimate dissatisfaction with the structure of Spring Happening, see Jeff Kelley, Childsplay: The Art of Allan Kaprow (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004), 57.

2. Allan Kaprow: Art as Life opened at the Haus der Dunst, Munich, in October 2006 and traveled to a number of other venues in Europe and the US. Gutai: Splendid Playground opened at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, in February 2013.

3. See, for example, Yve-Alain Bois’s entry on Gutai in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, vol. 2, 1945 to the Present (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 373-75.