Catherine Opie, The Land in Which We Live

“On behalf of the Land and everything living on it, new image wars must be waged.”

– Lucy Lippard

Internationally renowned artist/photographer/activist Catherine Opie is most often associated with her portraits addressing sexual identity and gender politics. Much of her work is shocking, in the tradition of artists like Robert Mapplethorpe. The Land in Which We Live, her recent exhibition of large-scale landscape photographs at The Current in Stowe, VT was presented under the umbrella of climate change. This appears, at first glance, to be a departure for Opie. The landscapes are devoid of people and not overtly beautiful or conventionally awe inspiring. They are silent, emotionally distant. Most of the work is untitled, produced in numbered series. In Untitled (Swamps #2), an alligator is lurking in the center foreground, at the edge of a lilypond. A scraggly, undifferentiated scrub-brush-like vista stretches behind the gator, as far as you can see. Two dead-looking trees act as vertical counterpoints. There is something menacing about this scene. Untitled (Swamps #4) has the whiff of spring. There is a tangle of fuzzy greenery, ferns, and a stream meanders through. Contradictorily, (Swamps #7) is both sharply real and abstract. The brownish web of dead or dying underbrush slices the image in half with a vapid pale gray sky reflected in the same tone in the water at the bottom of the image. No human or animal presence is to be seen. In (Swamps #8) the white/grey waterway presents a path into the interior of the swamp. Unappealing grey moss hangs over the foreground like cobwebs yet greenery lurks beyond. Is this world on the verge of living or dying?

Then there are the blurred images. Taken out of context they appear devoid of meaning. Photos like Untitled #5 (Yosemite Valley) are frustratingly opaque. Is Opie attempting to send the viewer a message? She has thrown an out of focus veil over the image making the subject undefinable. Perhaps she is saying nature is already disappearing from our view. We are too late to save it. In Yosemite Falls #2 and #4 Opie returns us to the elements of nature we recognize: trees, cliffs, and water, that are still here. The waterfall plunges hundreds of feet down, slicing through rock to the valley floor below. It is majestic.

In 2021 Opie was named UCLA’s Art Department Chair and that same year Catherine Opie, a monograph, was published by Phaidon. In the book, Opie’s hard to codify work is organized roughly into three categories; “People”, “Places”, and “Politics.” These broad classifications don’t really help much in understanding how the individual parts of Opie’s oeuvre fit together in one whole. As consumers of art and as writers about art we look to snag threads that can lead us, visually, through the evolution of an artist’s career. In Opie’s case we need to make leaps in our attempts to understand her concerns. The evidence she provides is ambiguous. She prefers it that way.

Her early career breakthrough works were portraits focusing on friends and family from the Queer community taken at the height of the AIDS epidemic in the mid to late 1990s. Of these, her still painfully vulnerable Self-portrait/Pervert showing her leather-hooded head, her half naked, heavily pierced body with the word Pervert literally carved, still oozing fresh blood across her chest, is perhaps the most well-known. It was exhibited at the 1995 Whitney Biennial. But how can we reconcile this work with her landscapes, and anything connected to the climate crisis we find ourselves facing today? Opie says she is, “looking for a broader understanding of how we actually get to be a better world…” She intends her photography to be part of a conversation, bearing witness rather than convincing us to see one immutable truth. Her work raises more questions than it answers.

How does our environment shape our identity? “I think about landscape as ever shifting its own vulnerability—like the human body”—Opie goes on to say, “We will be losing things… And so, in the same way that I lost my friends through AIDS and cherish the portraits I made of them, I think the landscape is something that we need to be reminded about and bear witness to.”

Bearing witness is one of the most significant ways artists can reflect on who we are and our impact on the world. It is this witnessing that is being practiced by the many artists, gallerists, and curators all who are engaged with the project Extraction: Art at the Edge of the Abyss, one of the most extensive art movements focused on climate change activism in the new millennium. The effects of climate change are increasingly undeniable. Polluted ground water, frequent floods interspersed with longer droughts, never ending wildfires, bigger and more catastrophic storms, are being driven in large part by extraction technologies removing vast amounts of resources from the earth. To maintain our consumer-based culture we need fuel and precious minerals necessary for everything requiring a computer chip. We acquire these commodities by digging or pumping or flushing or exploding vast areas, leaving scars on the land like open wounds.

In 2017, two visionaries from Montana, journalist Edwin Dobbs and fine art book printer/editor Peter Koch, founder of the nonprofit Codex Foundation, established the Extraction Project. Defined as “a global art movement in defense of the planet” they faced challenges, but the stakes could not be higher. Their own state is a prime example. Montana is home to 16 Superfund sites, some of the largest in the country. These areas and other international sites are so polluted and hazardous to human health some have been designated “Sacrifice Zones,” land and water irretrievably lost, no longer able to support life.

Dobbs died in 2019 and although Koch is battling cancer, he was able to build out a massive infrastructure of resources and like-minded cultural collaborators who would, “raise a ruckus” to move beyond politics and use art to motivate people “to confront the abyss with your whole being.” One of Koch’s collaborators representing the next generation of artist/activists is Sam Pelts. In a recent interview Pelts told us, “Part of the problem in confronting climate change is the invisibility of the causes. Extraction is at the root of all environmental problems, including climate change. Artists have the power to show us, in a very real way what that looks like.”

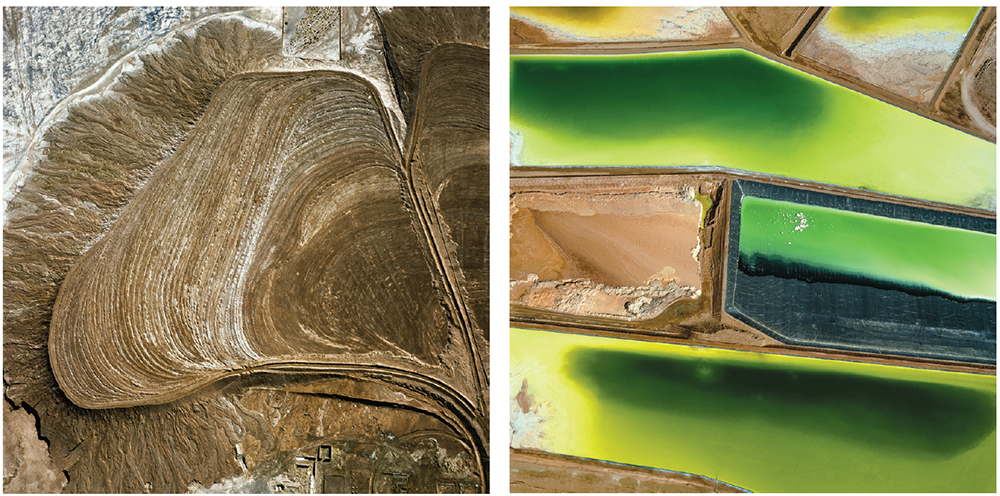

Photographer David Maisel, who has made natural resource extraction and its consequences his focus for nearly 30 years, is one of the more than 500 artists included in Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss. He shows us environmental devastation that can’t be denied. His series Desolation Desert on the transformation of Chile’s vast Atacama Desert into an unworldly landscape is both painterly and horrifying. In American Mine he explores sites, including the Berkeley Mine in Butte, Montana whose surreal colors belie the fact that the open pit is filled with poisoned water a mile deep and 900 feet wide.

Since the fine art of letter press printing was Koch’s expertise, Pelts said, “We kicked off the project by pairing 26 notable poets, artists, and writers with an equal number of highly regarded letterpress printers from four countries.” Famed Canadian writer Margaret Atwood agreed to participate as did 2019 Pulitzer Prize winners Forrest Gander and Eliza Griswold. “Each was invited to produce a broadside/print for a limited editioned portfolio titled WORDS on the Edge which is being sold to raise funds for the project.”

By the end of 2021 The Extraction Project had produced over 60 exhibitions, performances, installations, land art, street art, poetry readings and cross-media events. An inexpensively produced catalogue was created for the project. Modeled on the style of the iconic, 1960s counterculture publication The Whole Earth Catalogue, it functions as a guidebook to this multi-layered art movement. A comprehensive directory of the sites on the Extraction website reveals the geographic and cultural scope of the initiative.

Now, following a whirlwind year of organizing successful exhibitions under the Extraction Project umbrella, Pelts reminds us, “merely bearing witness is not enough…the history of art making has a moral weight behind it. Indigenous artists, shaman had the ability to visualize the future…we have the problem of a lack of imagination. It is a cultural problem in the way we view the world.” Artists like Catherine Opie, and those committed to the Extraction Project are working hard to help us all see where the truth lies in the future.