Laurie Simmons

Laurie Simmons is a master manipulator. Over a four-decade career, she’s used scale and dimension in tiny vignettes that penetrate the American dream using macro photography of dolls and toy furniture. Evoking childhood dioramas and suburban ennui, she critiques gender stereotypes and the artifice of our daily lives—what sociologist Erving Goffman termed “front stage” behavior; the performative lengths we go to for a perceived audience. With their vacant-eyed plastic dolls and couches only inches long, her images rouse a Betty Draper isolated domesticity, leaving viewers in an aesthetic vertigo: How real is this scene? Which objects are true to size?

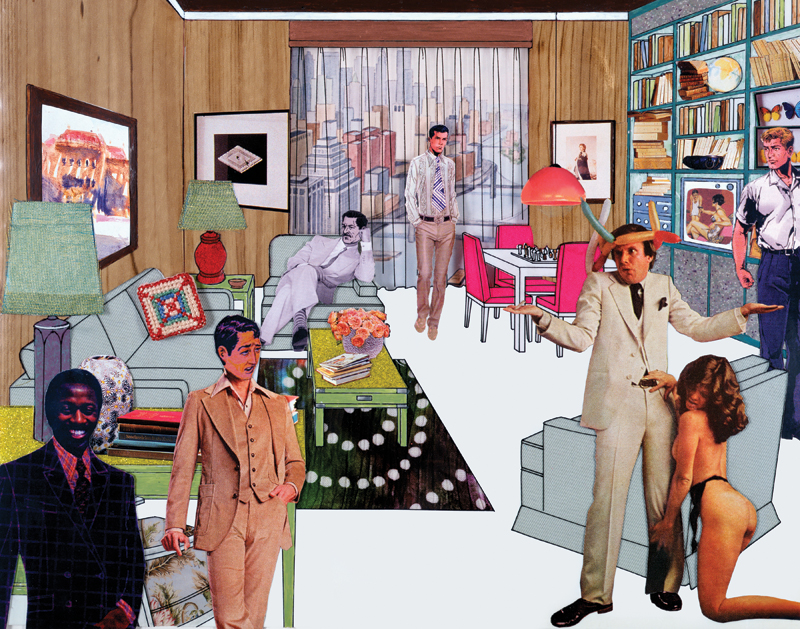

The Instant Decorator (Wood Paneled Den, Bachelor Party), 2004.

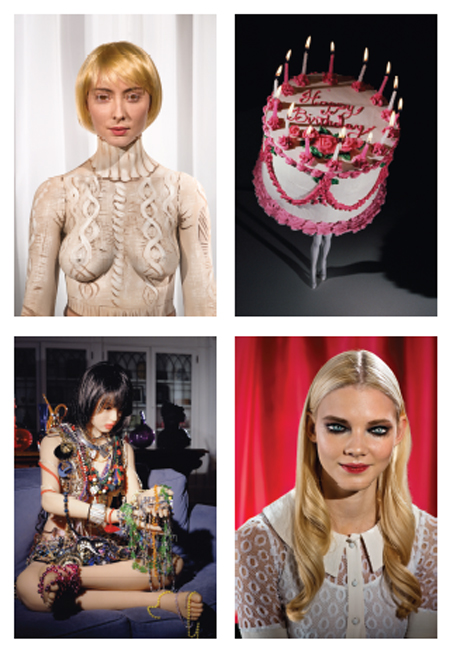

With her major retrospective Big Camera/Little Camera at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago this spring, Simmons takes her place as a legend of the Pictures Generation, an iconic group that includes Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman. Her photographs and films are staunchly feminist, whether or not women are depicted: The Big Figures/Cowboys (1979) series—shot with husband and painter Carroll Dunham’s boyhood action figures—upends the masculine hero myth by staging what appears, with sleight of eye, to approximate stills from old Westerns. That is not to say that Simmons has ever shied from female sexuality and the body politic. Most notably, The Love Doll (2009–2011) series features hyperrealistic, anatomically correct, life-size Japanese dolls in hauntingly lonely scenes. Yet a solely feminist read of her work is a limiting one, Simmons cautions. “If it doesn’t resonate for me on the psychological, the political, the personal,” she says, “it’s not going to leave my studio.”

Perhaps most remarkably, Simmons’s practice presages so much of social media. In the early 2000s, she created over-the-top photographed collages such as The Instant Decorator (2001–2004), inspired by a 1976 home decor manual of the same name. Today, the work feels like a fresh riff on Pinterest, anticipating the height of virtual design fetish years in advance. Recently, in Some New (2018), subjects, including children Grace and Lena Dunham, select personas—Lena as Audrey Hepburn, Grace as Rudolph Valentino—and sit for Simmons, wearing painted bodysuits instead of physical clothing. “It’s a lot about life on the internet, our ability to create a persona or an avatar,” she explains of these portraits. “You know, I had a brief moment in Second Life [the 3D digital world], and I thought, I’ve got to get out of here because I’ll never leave, it was so exciting.” Indeed that notion of fantasy perfectionism and alter-ego manifests in How We See (2015), a body of work in which Simmons—influenced by kigurumi, a subgenre of Japanese cosplay—photographs models, whose irises and pupils are painted over their closed eyelids. Forty years in, Simmons has come full circle: where once her tiny inanimate figures radiated human emotion, now her flesh-and-blood subjects embody vacant plasticity.

It is a perfect, mild snowy day at Simmons’s Cornwall, CT, property. The Georgian brick home—formerly an administrative building for Marvelwood School—which she and Dunham purchased in 2007, has become famous in its own right. The house and adjacent barn, a rustic utopia where both artists work, figure prominently in My Art (2016), Simmons’s first feature-length film, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival. In addition to being the director and screenwriter, she stars as Ellie Shine, a single 65-year-old New York artist who grapples with aging and career recognition on the grounds of a friend’s summer house. Simmons held previous roles in Lena Dunham’s Tiny Furniture and much-lauded HBO series, Girls. In Simmons’s 45-minute musical, The Music of Regret (2006), most characters are either puppets or male ventriloquist dummies from one of her earlier photograph series (though Meryl Streep appears in the film).

Clockwise from top left: Some New: Hayden Dunham (White), 2018. Walking Cake II (Color), 1989. How We See/Look 1/Daria, 2014. The Love Doll/ Day 22 (20 Pounds of Jewelry), 2010.

Off-screen, the couple’s home attracts a frequent assemblage of creatives—when you mention a trip to Cornwall, people know what you mean. “I walked in the front door, and it was like when people say you have glimpses of cosmic consciousness or unbounded awareness,” Simmons recalls of her first time in the home. “I feel like I saw my whole art future in this house. I feel like I saw the movie. I saw the work I would make, but just for an instant.”

It’s not a surprise that her home is a tour de force in light of a career exploring neo-domestic ideals and the aspirational power of interior decorating. Walls are filled with a soulful yet punchy collection of friends’ art-trades: Sarah Charlesworth, Marilyn Minter, to name a few. Simmons tells me they installed their black and white patio specifically for shooting. “My dream was always to live in a big house,” say Simmons. “I think that comes from the fact that my parents were both first-generation Americans. The idea of the house and the home as the apotheosis, the epitome of the American dream is all over my work. I mean, it’s all over every picture.”

In fact, the kitchen emanates a conscious warmth one wouldn’t necessarily associate with creative intensity. But Dunham’s Norwegian gallery team is in town and it’s easy to see how the husband-and-wife team, married since 1983 (Simmons calls Dunham “Tip”), admire their respective prowess. Alongside an elegant presentation of scones and tea, Simmons’s assistant has brought local sandwiches for everybody. For the interview, Simmons’s chooses her upstairs office space backed by several of her large-scale The Mess (2017) photographs. They are an extension of Simmons’s obsession with plastic props, inventories everyday household items (grape soda, liquid dish soap, Cap’n Crunch) into color-coded abstractions. Such playfulness harkens Walking & Lying Objects (1987–1991), in which Simmons animates a giant camera or gun with human legs. The huge pink icing, candlelit birthday cake prop from Music of Regret—instantly… birthday cake—instantly identifiable to any student of Simmons—is the pièce de résistance of the barn tour, residing at the center of an empty attic loft. “I felt very satisfied, but it’s an odd feeling to do this summary of your years working that has so many omissions,” Simmons explains of her survey traveling from the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth to Chicago this spring. “I’m already thinking about my next retrospective. I’ve got so much left to do. I’m just scratching the surface of making film, and I have so many ideas.” She pauses and takes a deep breath. “I mean, I’m panicked about the amount of things I want to do. You know, sometimes I feel like a young artist.”

Jacoba Urist is a Manhattan-based art journalist, who writes from the Connecticut shoreline part of the year.