Museums in Our Post-Truth Society

Davis Museum security officer David Pierre reads a wall note in the spot usually occupied by a 1794–96 portrait of George Washington painted in Wilmington, DE, by artist Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller of Stockholm, Sweden, for the Davis Museum’s Art-Less exhibit. Photo: Art Illman/MetroWest Daily News.

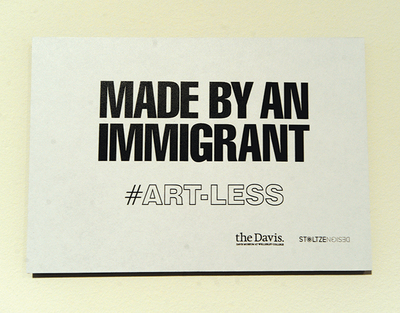

For a week in February, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College staged Art-Less, which shrouded or deinstalled 120 works that were created or donated by immigrants, about a fifth of its collection on view. The event was a subtle yet powerful protest of President Trump’s travel ban directed at seven Muslim-majority countries, its power drawn in large part on a simple truth: Immigrants have a tremendous impact on places like Wellesley and, by extension, the entire country.

Today more than ever museums offer a compass. Inside their spaces we find reality. When people encounter a work of art, an antiquity, a scientific breakthrough, a historical event, a wonder of nature or any of the other objects museums offer, they experience authenticity. This, they must acknowledge, is the real deal. Many other aspects of life are confusing, perhaps, but this object in this moment is the truth. The chaotic maelstrom of politics fades into the background.

Since the day after the election, museums throughout New England have become sanctuaries. They are places of quiet, contemplation, hope, perspective, history, escape, and above all, truth. Museums have often provided comfort in times of public crisis such as 9/11, Sandy Hook or the Boston Marathon bombing. In a normal election year, museums do not go into crisis mode; 2016, however, was not a normal election year.

Inauguration Day, usually a pageant celebrating America’s peaceful transfer of power, this year heralded a new normal of protests, demonstrations and clashes. The arts community mobilized the J20 Art Strike. Museums around the country, including Boston’s ICA and RISD Museum, offered free or voluntary admission on January 20 (or closed altogether) to encourage reflection and conversation about the incoming regime.

Lee Friedlander, Untitled, from the series Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, 1957 (printed later), gelatin silver print. Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Maria and Lee Friedlander, hon. 2004. © Lee Friedlander, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Eakins Press Foundation.

Since then, news from Washington, D.C. has been a fire hose of cabinet appointments, executive orders, rumors and tweets that appear to be anathema to museums and the arts community: an immigration ban that impacts scholars and artists; a wall that demeans many museum workers; climate change skepticism a litmus test for political appointment; and existential threats to the National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, Institute of Museum and Library Services and other federal agencies that support

museum programs.

But regardless of your politics, the most unsettling result of the election has been an assault on reality itself. Politics has always employed embellishment and truth shading as means to ends. But in our new world order, mendacity has become the norm. We now live in a “post-truth society.” The White House peddles so-called “alternative facts” with a straight face. Conspiracy theories dominate the headlines. With so many lies, falsehoods and obfuscations masquerading as truth, it is hard to determine fact from fiction. Reality has become relative.

Last October, we saw a dramatic example of how museums affirm reality when Michael Bloomberg donated $50 million to the Museum of Science, Boston. Bloomberg, a three-term mayor of New York who made billions in financial technology, is well-schooled in cage-match politics. He’s an Independent straddling the polarities of Red and Blue, a witness to the worldviews of both sides. This $50 million didn’t go towards a political cause. This $50 million went to a museum that inspired him as a youngster growing up in Medford, MA, and which continues to define for him what is real.

A sign replaces artwork made by an immigrant to the United States, posted at Wellesley College’s Davis Museum for its Art-Less exhibit. Photo: Art Illman/MetroWest Daily News.

“You go around the museum today, and you touch a button and things happen. You become part of the exhibit, and that’s what makes science relevant to you,” said Bloomberg, according to the Boston Globe article announcing the gift. Bloomberg particularly recalled the museum’s cross-section of a giant 2,000-year-old sequoia tree, with which museum educators taught him “the value of intellectual honesty.” Clearly, to Bloomberg, this is a place with deep meaning, not because of theories or worldviews espoused, but because of the intensely authentic experiences taking place there. “I went every Saturday, and it changed my life,” Bloomberg said. Not all museum visitors are capable of expressing their appreciation with a multimillion-dollar gift. But because museums connect their visitors with the authentic, they can ground and center them. Visitors find objectivity in the objects. This is why museums are considered among the most trusted sources of information in the U.S.

Museums now must determine how they can leverage that trust to counteract the forces of propaganda. Can museums employ it to redefine reality for communities bewildered by political crosscurrents? Is it possible for museums to help unify and heal our polarized society? Restore civility to our civic dialogue? Help unstick the wheels of government?

Museums, I believe, have an extraordinary responsibility to leverage their social capital in service to a divided nation. If there was ever a time when museums could demonstrate their value as essential to their communities, that time is now. In an era when the media is labeled “the enemy of the American people” and its ability to challenge “alternative facts” and outright falsehood is diminished, museums can and should augment efforts to anchor society with reality.

This fall, the 99th Annual NEMA Conference meets in Falmouth, MA, under the theme “Truth & Trust: Museums in a Polarized Society.” There, we will wrestle with how collections and programs convey authenticity, how museums can help clarify reality, how they can unite opposing voices, provide safe space for visitors and encourage civil discourse.

Over the coming months, our regional and national museum community will be creating the playbook for our own resistance to political propaganda. We recognize the urgency: Unless we unite quickly around what is true and oppose the relativism of facts, we will find our institutions and ourselves dangerously adrift. We urge your support and activism in this important time. Speak out for museums and the reality they represent by contacting your members of Congress. Speak out in favor of facts, challenge propaganda wherever you hear it, and visit museums to rekindle your connection with the authentic.

Dan Yaeger is the executive director of the New England Museum Association.