The 51%

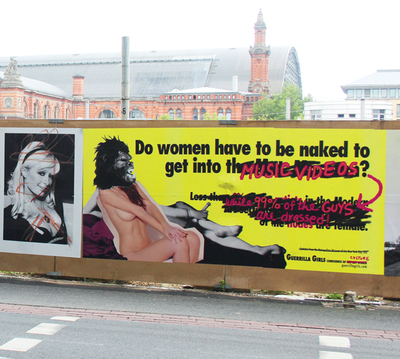

Guerrilla Girls, Do Women Have to be Naked to Get Into Music Videos, 2015, Bremen. Photo: Guerrilla Girls.

In 1985 a group of masked female artists called the Guerrilla Girls began papering New York City with posters that read, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” Below this provocative question (and an image of a reclining nude woman wearing a gorilla mask) was this incendiary statistic: “Less than 5% of artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

“Very little has changed since the first organized protests by women artists back in the 1970s,” says Deborah Johnson, professor of art history and women’s studies at Providence College in Rhode Island. Despite the fact that feminism is more visible than ever in American popular culture, gender disparity persists malignantly in the art world. Women artists are less likely to pull in big prices at auction, their work is less likely to make it into a museum’s permanent collection and they continue to have a more difficult time finding gallery representation than their male counterparts.

“Ultimately, I believe change has to come from museums. Galleries come and go. Museums are the repositories of our culture,” says Kathrine Lemke Waste, a California-based painter and president of the board of directors at American Women Artists (AWA). Founded in 1990, AWA is a national nonprofit arts organization that seeks to promote the work of female-identifying artists. Over the past 25 years, AWA has staged dozens of gallery shows, but in 2015 they decided to shift their focus and work solely on producing museum exhibits.

“You can’t separate museums numbers from gallery numbers,” Waste explains. Museum purchases directly influence auction prices, and when gallery owners are choosing which artists to represent, they often go with those who can command high prices at auction—or artists they believe will someday do so—women like Joan Mitchell, Yayoi Kusama, Louise Bourgeois, Agnes Martin or Cindy Sherman. Historically, though, the highest selling pieces have all been works created by men, almost without exception.

To combat this problem, the AWA has pledged to stage one museum show every year for the next 25 years, starting with a 2016 exhibit at The Bennington Center for the Arts in Vermont. The juried show opens on September 22 and will feature work by AWA members, including painters Nancy Boren, Carol Arnold and Bethanne Cople. Four additional museum shows have been confirmed to take place in Arizona, California, New York and Colorado.

“We want to bring a little noise to the issue, and we are focusing on museums as one way to do that,” explains Diane Swanson, executive director of AWA. “There is no difference in work created by male or female artists; look at a landscape—there is no way to tell the gender identity of a painter. As long as there is a reason for the AWA to exist, we will continue to work to highlight women artists and to change the conversation.”

“At this point,” adds Waste, “there’s a very real sense of indignation. How are we still talking about this?”

Another factor that makes some gallery owners reluctant to represent women is their perceived lack of commitment to the artistic life. “There is the old, damaging trope that women are not reliable workers because they will get married, pregnant and then drop out of the workforce,” says Johnson.

Unfortunately, the idea that children will infringe upon one’s artistic output seems to apply only to women. “Nobody ever mentions your kids to you when you’re a male artist,” says Beth Kantrowitz, co-owner of Drive-By Projects, a gallery located in Watertown, MA. “People used to make fun of us because we showed only women,” she remembers. “I’d hear things like, ‘You guys only show skirts!’ But I’ve been in the business for 20 years and what I’m interested in—what I’ve always been interested in—is the quality of work.”

Over the years, both Kantrowitz and her business partner, Kathleen O’Hara, have noticed something interesting about the way male artists promote their work. “Men tend to value their work more,” Kantrowitz says. “I don’t think they say, ‘I’m a man so my work is worth more.’ But I believe they are often ready to charge higher than a woman might.”

Catherine Little Bert, director and owner of Bert Gallery in Providence, has observed a related trend. “What is curious to me is that there are a lot of men who are collecting women artists,” she says. At Bert Gallery, Bert shows historic women artists from New England, a genre that appeals to many collectors, including Terrence Murray, former chairman and chief executive officer at Bank of America. “He believes that, from an economic point of view, you get much better value from buying pieces by women,” Bert says. “The art gallery world is always looking at value. If you look at prices for women’s work, they’re much lower.” Smart collectors, she says, take advantage of the gender gap. “I think the marketplace will ultimately be a better advocate for women than the academic world,” she says.

Not everyone sees it this way, however. For Waste, the very idea that a work’s value is now considered synonymous with its price tag is troubling. She traces this attitude back to the 1980s, when moneyed investors started viewing art as a piece of the overall portfolio. “Why is women’s art valued less?” Waste asks rhetorically. “Because women’s perspectives are valued less.” For centuries, the male point of view has been considered universal—particularly the white male point of view. Hoping that the market—a space that is still controlled overwhelmingly by white men—will change how we culturally interpret the world is a dangerous gamble.

“Valuing art based on big bucks—well, that’s a very male way to view things,” Waste says. The market could be an advocate for women artists, but it also requires that we’re willing to view each work of art through a very specific lens. For Waste, Swanson and others, it’s important to take off the green-tinted glasses occasionally and see a piece for what it is and how it speaks to the viewer—not what number it has slapped on the back. Otherwise, we run the risk of continuing to walk around blind to the experiences, perspectives and talents of 51% of our population. “Art, which we believe is telling the story of humanity, has been telling less than half the story,” Johnson adds. “That’s a huge problem.”

Katy Kelleher is a writer and editor living in Maine. Her first book, an in-depth look at maker culture in Maine, is due out in 2017 from Princeton Architectural Press.