The Strange World of Albrecht Dürer

When most of us talk of “devouring a book” we mean reading it avidly. In Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut of St. John Devouring the Book the saint is doing just that, literally. The written episode in the Book of Revelation is somewhat vaguer on the subject, but Dürer, using his imagination and perhaps his wish to enlighten a public that could not necessarily read, showed John chowing down a message from God, delivered by an angel whose legs are columns of fire.

To a contemporary public, the image is almost comical. Who would have thought it? Dürer? Funny? Well, yes, there are funny moments in the Clark Art Institute’s The Strange World of Albrecht Dürer, as well as moments that will appeal to anyone with interests ranging from the Protestant Reformation to anatomy to copyright law.

The Clark is well-positioned to stage this show of seventy-five Dürer prints. The Institute owns over 300 Dürer sheets, thanks largely to a 1968 purchase from the collection of Tomás Joseph Harris, who died in 1964. Had Harris lived in Dürer’s day, he and his activities would have been a worthy subject for an artist wrapped up in the turmoil of his times. Harris was part of the British intelligence service during World War II, supplying false information to the Nazis about the Normandy invasion.

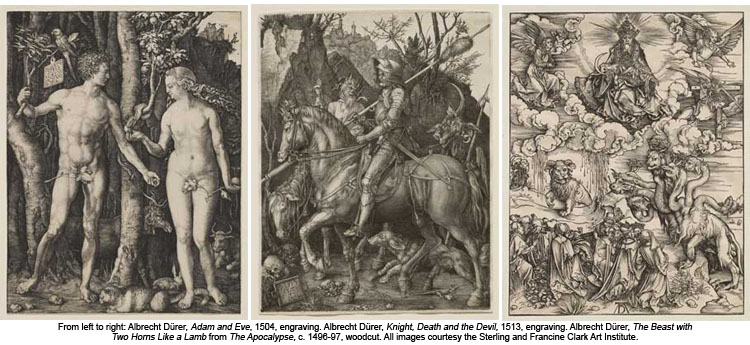

If the dark days of World War II seemed perhaps the end of civilization, the run-up to the year 1500 really did. It was then that Dürer rose to the challenge of depicting the Apocalypse, as foretold in the Book of Revelation. Into these fifteen woodcuts he packed not only earthly life, but also that of heaven and hell. “Packed” is the operable verb here. It is astounding what Dürer could cram onto a not very big piece of paper. He used striated lines brilliantly, for instance, by the hundreds. In horizontals, they convey calm. In diagonals, they convey hectic unrest or the beatific rays of God’s sun.

Dürer’s prints are stunning. He couldn’t let loose his imagination in the paintings he made at the command of influential patrons. In the prints, he did. Take St. Eustace, his largest engraving, which tells the tale of the legendary hunter frozen by the sight of a stag with a cross growing between its antlers. In the background is a towering landscape capped by an obviously Germanic medieval castle. The detail is staggering: the softness of the dogs’ and horse’s flesh, the tiny plants underfoot.

The Apocalypse, the end of the world, is the beginning of the show. The woodcuts were actually a book, and, if you look closely, you see the printing on the backs of the pages. Among the images here are those that track St. John, including one of him naked in a tub over a fire, looking not all that perturbed. It turns out that he survived an attempt to boil him to death. Behind him is a bunch of unsavory men, including the one who has sentenced him, wearing the turbaned garb of an Ottoman merchant. Struggles between Christians and their Arab brethren are nothing new, the show’s curator, Jay Clarke, points out. Nor is Dürer’s fusion of many centuries, so that biblical, classical and fifteenth-century garb appear side by side. This is nothing specific to Dürer: artists of the very early Renaissance did likewise.

The wall texts and brochure accompanying the exhibition make every effort to connect Dürer’s day and our own, although it’s not always a success. Most museum-goers do indeed appreciate one theme per room, but, for instance, the “War and Suffering” gallery that attempts to connect the battles of the Reformation across Europe with the violence of twenty-first century video games and comic books doesn’t quite succeed. Most of what’s here are images of the Passion, including one tiny engraving of Christ Carrying the Cross that is breathtaking. No bigger than the palm of a hand, it features a play of rich blacks, delicately deployed, with Christ at the center of the tumult, pausing for a moment to stop and look back at his mother. It’s an achingly tender moment, and it doesn’t connect at all with the room’s theme. It does bring up the question of how Dürer created such dense imagery in such a tiny space. Engraving, Clarke points out, requires both hands at once. Magnifying glasses existed in Dürer’s time, and he may have rigged up something resembling the reading glasses of our era. Yet, while Dürer’s career is not exactly unexamined, no one really knows how he worked, or for how long he could work on an intense print before taking a rest.

Dürer was fascinated by anatomy, both human and that of horses, dogs, and even a rhinoceros. The rhino was on a ship from Portugal to Rome. The ship sank, and Dürer had to rely primarily on others’ accounts of what the beast looked like. Dürer’s woodcut is curious indeed, with immense diversity of textures, including the animal’s armor-like hide and scaly legs.

The art historian Erwin Panofsky wrote that Germany’s great contribution to culture was graphic arts, hence Dürer’s power through the centuries. Even Hitler co-opted the artist’s style to present himself to his public. Dürer’s ongoing pull is even witnessed by his copyright efforts, very early in the history of art. He objected to Italian artists’ plagiarizing his works, and he took his case to court. The court ruled that while his images weren’t eligible for copyright, the monogram he used was. So when you see a true Dürer print, those intertwined initials, AD, are front and center—even more front and center after that long-ago court ruling.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Christine Temin was the art and dance critic at the Boston Globe for over two decades and now writes for a variety of international publications. She has taught at Middlebury College, Wellesley College, and Harvard University. Her most recent book is Behind the Scenes at Boston Ballet, published by the University Press of Florida.