!Women Art Revolution

!Women Art Revolution (!W.A.R.) begins with a clever gambit. Filmmaker and artist Lynn Hershman Leeson points her camera at visitors outside a prominent American art museum and asks, “Can you name three women artists?”

Pause. Someone mentions Frida Kahlo. But the others, clearly stumped, can only mumble, “Uhhhh.”

That Kahlo is the only female artist the average American can name is a fine reason for Leeson’s film !W.A.R. to exist. Based on forty years of interview footage Leeson shot of major figures in the feminist art movement, the documentary aims to fill in the gaps of a forgotten chapter—it’s a book, really—in the story of art. “This film is the remains of an insistent history that refused to wait any longer to be told,” says Leeson, also the film’s narrator.

A feminist art veteran specializing in site-specific, performance, and interactive media works, Leeson has also directed the feature films Teknolust, Conceiving Ada, and Strange Culture (all starring Tilda Swinton). !W.A.R. is her first feature documentary, and the result is clearly a labor of love. Leeson began to document the feminist art movement back in 1966; in 2004, she rediscovered hundreds of hours of footage with artists, feminists, filmmakers, and curators such as Miranda July, Yvonne Rainer, Judy Chicago, Marina Abramovic, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Marcia Tucker, Carolee Schneemann, and dozens of other groundbreaking figures.

“I felt a tremendous responsibility to find the story inside that raw footage and to honor the women who struggled to invent themselves,” Leeson writes in the film’s press materials. Beginning with feminism’s emergence after the sixties, Leeson takes us through the major developments in the women’s art movement. She shows how women, seeing the results of antiwar and civil rights protests, began to march for their own kind. Like all change, the movement began with humble steps—a demonstration against the Miss America pageant, Faith Ringgold complaining that New York galleries featured no women. Before long, female artists began challenging traditional views of gender, body image, and sexuality protesting against major museums who systematically excluded women artists; and forming their own alternative institutions and art spaces.

The early seventies was the movement’s heyday. We see leaders such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro establish the first-ever academic Feminist Art Programs at Fresno State and CalArts in 1971. We see the creation of the first large-scale public feminist art installation in a building in Hollywood dubbed Womanhouse. In 1972, the Artists in Residence gallery, the first-ever women’s artists collective, opens its doors. In 1973, Chicago and two others open the Feminist Studio Workshop, the first independent school for women artists. “There were almost no women artists visible at all,” Chicago says. The world needed “remedial education.”

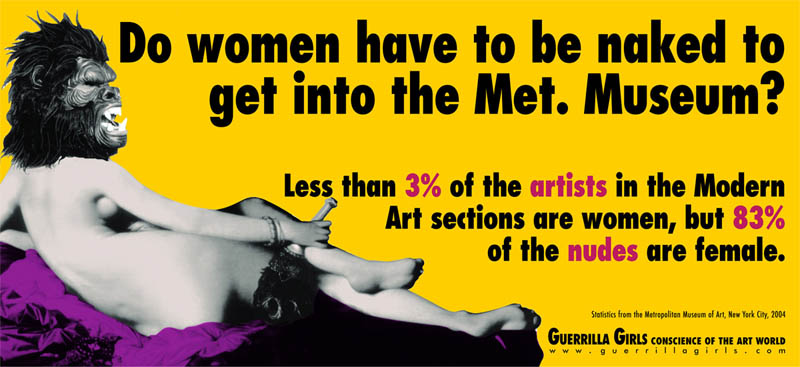

!W.A.R. successfully conveys the urgency and courage of that heady time. Leeson intersperses her interviews with archival footage of early performance art, and much of it still feels relevant. Semiotics of the Kitchen, a short 1975 video, depicts Martha Rosler parodying a cooking show host and demonstrating kitchen tasks in nonsensical (and sometimes violent) ways; the performance piece deconstructs domestic servitude. Rosler and, later on, the Guerrilla Girls—those anonymous, gorilla mask-wearing activists who used statistics to point out sexism in the art world—proved art activism need not be a tiresome diatribe about righting wrongs. Rather, many artists embraced humor as a way to get audiences to swallow a bigger political message. Eleanor Antin’s photo series My Kingdom Fell Upon Hard Times, which depicts her as a mustached, fictional monarch wandering a modern urbanscape and talking to his “subjects”; and Ana Mendieta’s fictional identity self-portrait (i.e., photographing herself as feathered and bearded), both show that cross-dressing and experiments with role-playing are as much about agitprop as ironic play.

!W.A.R. successfully conveys the urgency and courage of that heady time. Leeson intersperses her interviews with archival footage of early performance art, and much of it still feels relevant. Semiotics of the Kitchen, a short 1975 video, depicts Martha Rosler parodying a cooking show host and demonstrating kitchen tasks in nonsensical (and sometimes violent) ways; the performance piece deconstructs domestic servitude. Rosler and, later on, the Guerrilla Girls—those anonymous, gorilla mask-wearing activists who used statistics to point out sexism in the art world—proved art activism need not be a tiresome diatribe about righting wrongs. Rather, many artists embraced humor as a way to get audiences to swallow a bigger political message. Eleanor Antin’s photo series My Kingdom Fell Upon Hard Times, which depicts her as a mustached, fictional monarch wandering a modern urbanscape and talking to his “subjects”; and Ana Mendieta’s fictional identity self-portrait (i.e., photographing herself as feathered and bearded), both show that cross-dressing and experiments with role-playing are as much about agitprop as ironic play.

Later, as the seventies becomes the eighties, the initial movement splinters, with inevitable factionings and fallings out. Even the Guerrilla Girls split up over ownership of their name. The Equal Rights Amendment dies; the Reagan and AIDS era begins. Mendieta falls to her death in 1985 and her husband Carl Andre, charged with her murder, is acquitted, which galvanizes a major protest. In 1990, Judy Chicago installs her infamous Dinner Party, a huge triangular dinner table for history’s absent, marginalized women with its vaginal motif place-settings. The installation is denounced in Congress as obscene and becomes a lightning rod for conservative protest against publicly funded art. Chicago relishes the attention.

Despite the wonderful material, the film feels less deliberately made than winnowed-down. Much of the footage was shot ten or twenty years ago. Digital animations, a score by Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein, and a few interviews with younger artists like Janine Antoni liven up the proceedings, but !W.A.R. still radiates a frozen-in-time, archival salvage quality. She might have included more interviews from the past couple of years. Likewise, Leeson tries to inject the film with personal gravitas, telling the story of why !W.A.R. took forty-two years to make, but this angle feels like a distraction. She claims the film floundered because she had not found an ending, but !W.A.R. peters out more than concludes.

Despite these drawbacks, Leeson should be commended for telling this forgotten tale of feminist art. !W.A.R. brings back the urgency of those days. And it may still effect change: The documentary is being released with a companion comic book, in a style reminiscent of the sixties underground Zap Comix, and it includes some eighty pages of resource and curriculum material, which the filmmakers hope will be used in classrooms.

As !W.A.R. points out, the feminist art movement never changed the way art is produced, bought, distributed, and exhibited, as the artists had hoped. But the incessant protesting and posturing succeeded in busting down barriers. For that, women artists everywhere should be thankful. In equal measure, nostalgists and students of the era might also mourn this loss: That the practice of taking to the streets or occupying a building to compel change, once instinctual, has become forgotten in complacent twenty-first century America.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, and is a film and book critic for The Boston Globe. More information about him can be found on his website at www.fantasyfreaksbook.com.