In Their Own Words

The End Depends on the Beginning:

Coming Full Circle at Yale

Jock Reynolds

“The end depends on the beginning.” This phrase, translated from the Latin finis origine pendet, has long held special meaning in my life. It comes to mind again as I prepare to end my 20 years of service at the Yale University Art Gallery. It has been a great privilege to help steward and conserve the gallery’s iconic buildings and remarkable art collection, and to fulfill the museum’s mission—alongside talented curators, educators, artists, staff members, donors and volunteers—of providing visual pleasure and knowledge to museumgoers of all ages.

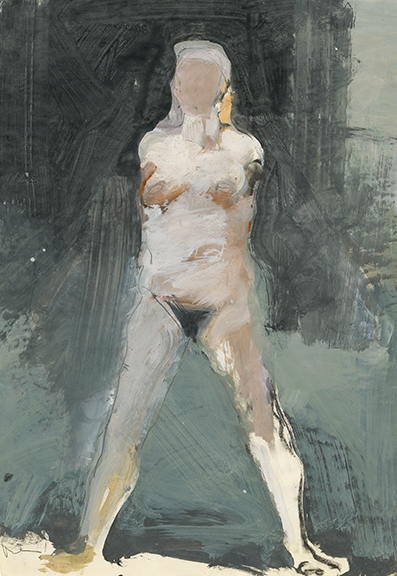

I have chosen to link my “ending” at Yale to the “beginning” I enjoyed as an MFA student at the University of California, Davis. In 1972, I was invited to be the teaching assistant to the sculptor Manuel Neri (b. 1930), a prominent figure in the San Francisco art scene. Beginning in the mid-20th century, a major trend in American art developed, one that adapted painterly techniques to render its subjects in powerful new ways. Neri, along with artists Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, Wayne Thiebaud and others, renounced abstraction and chose instead to include the human figure and other recognizable subjects in their work—albeit using the vigorous brushwork and strong compositional elements of their abstract expressionist contemporaries. In addition to being an accomplished artist, Neri was a respected teacher, and I quickly learned a great deal from him. He taught me not only how to use all manner of material and tools, such as spatulas, chisels, rasps and knives, but also how to become more present and observant while working on a creative project. In other words, Neri became a formative exemplar. So, I am thrilled to mount, all these years later, Manuel Neri: The Human Figure in Plaster and on Paper, a testament to my early mentor.

The human figure was an essential part of Neri’s oeuvre. I co-taught an undergraduate studio course with him in which we challenged our students in each week’s three-hour session to represent the human figure in plaster, working from a live model. The students were asked to first look closely at the model as she held different poses and to draw each one very swiftly. Then the model held a longer pose, from which they were instructed to render a three-dimensional figure, using plaster as their medium—one of the most versatile materials used by sculptors throughout the history of art.

Neri himself was a master at such exercises. During our semester together, he invited me to his studio, where I observed firsthand how his creative practice directly inspired his teaching methods. Neri worked prodigiously and quickly. He started each of his sculptures by building a stable armature. Next, he would begin to realize a full-scale figure around that armature, working with multiple batches of plaster, expertly manipulating this material with his hands and with different tools, then layering on pigments and paint. His way of working was remarkably performative, and

it enthralled me.

One isn’t often able to witness at such close proximity the creative process of a great artist, so when I left UC Davis to begin my own career as an artist and teacher in San Francisco I never forgot Neri. In 1975, I cofounded 80 Langton Street, one of a number of alternative artists’ spaces—run by artists to help support each other across multiple creative disciplines—being established in San Francisco at that time. When it was my turn to organize an exhibition just one year later, I decided to invite Neri to create a sculptural figure in plaster every day for eight days, an installation that came to be titled The Remaking of Mary Julia: Sculpture in Process. I knew that Neri would ask Mary Julia Raahauge, his muse at the time, to serve as the model for such an endeavor, and I wanted to tip my hat to both of them and show my peers the remarkable work Neri would surely produce within even such a short period of time. Neri did exactly what I expected of him.

Now, some 40 years later, he and Anne Kohs, co-trustee of the Manuel Neri Trust, astounded me by generously donating more than 150 works by the artist to Yale. The gift includes explorations of the human figure—sculptures in plaster and studies in watercolor, graphite and other media—as well as a group of works that responds to the architecture of ancient sites in Latin America. Manuel Neri: The Human Figure in Plaster and on Paper celebrates this gift and serves as a wonderfully circular ending to my time at Yale, one that harkens back to my beginnings as an artist and makes evident the profound influence a great teacher can have on a student—something I have had the pleasure of witnessing here at Yale on so many occasions over the last 20 years. n

Jock Reynolds is the Henry J. Heinz II Director of the Yale University Art Gallery. He will be stepping down when his current term ends on June 30, 2018.

Manuel Neri: The Human Figure

in Plaster and on Paper

Yale University Art Gallery

New Haven, CT

artgallery.yale.edu

Through January 27, 2019

Beyond Architecture and Accessibility:

Increasing Art Museum Relevance

Dan L. Monroe

In the last quarter century, American art museums adopted two macro strategies—facility expansion and efforts to make art more “accessible”—to make themselves more central in the cultural life of the nation.

The extraordinary success of Frank Gehry’s 1997 Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao project inspired art museum leaders to enthusiastically embrace the idea that architecture could be a primary vehicle for making art museums more visible, popular and generously supported. Acting on this conviction, nearly every art museum in America has carried out a major facility expansion project during the past 20 years.

The idea that art needs to be more accessible derives from the conviction that the traditional art museum experience is “great.” However, not as many, or diverse kinds of people as desired, attend art museums. To account for this phenomenon, many art museum leaders have assumed there are impediments, such as admission policies, inconvenient hours, lack of inclusivity and so on that have acted to make art museum collections inaccessible. They have reasoned that if these presumed impediments are removed, then art museums will be far more successful in attracting and serving broad spectrum audiences.

Have facility expansion and efforts to increase accessibility to art made art museums more successful and influential? In some ways, yes. Art museums are far more visible today than they were in the past. But in other fundamental ways, no. Field-wide attendance at art museums has decreased by approximately 20% since the turn of the century.

Attendance should not be the sole metric of art museum success. However, it is important because it is a broad measure of relevance, and a 20% loss in field-wide attendance should be cause for serious concern. Oddly, it is not. There is currently no national discussion of this issue.

There are many possible reasons for absence of attention to decreasing field-wide attendance. Attendance at some art museums, including the Peabody Essex Museum, has increased dramatically over the past 20 years. Diversity, equity and financial stability have commanded leadership attention. Whatever the causes, continued failure to address field-wide attendance decreases is not in the best interest of art, art museums or national cultural life.

Why haven’t facility expansion and efforts to increase accessibility to art resulted in increased art museum attendance, financial support and influence?

The invention of the Internet and myriad new digital technologies have generated one of the greatest social and cultural transformations in history over the past quarter century. The Information Age created by these inventions has profoundly restructured global society and culture.

We now create 2.5 exabytes of information every day, the equivalent of 250,000 Libraries of Congress. Much of this information is digital, dynamic and interactive and it can be distributed almost instantly to half the world’s population. Vast numbers of people suddenly have the power to individually curate immense amounts of information to suit their individual needs and interests. As a testament to our compulsive need for information, the average American now spends seven hours a day acquiring and processing digital information.

The core historical audience for art museums—people who are highly educated—have been among those most profoundly affected by the Information Age. New digital technologies have extended the average work week for this group. The compulsion to acquire information has cut into other facets of life, and many people consequently feel extremely pressed for time. Competition for attention, time, energy and money is more intense than ever before. Not surprisingly, these dynamics are rapidly reshaping American cultural life and affecting art museums.

The recent Culture Track report by LaPlaca Cohen documents profound changes in the way people define culture and in what they want from cultural activities. A visit to a taco stand is now considered a cultural activity. People of all ages cite fun as their highest priority for cultural experiences of all kinds. Many people of color and people under the age of 40 do not consider art museums as cultural attractions that interest them.

Many of the anticipated benefits of facility expansion and efforts to increase accessibility to art have been washed out by massive technological, social and cultural changes that have acted to make fewer and fewer people consider the traditional art museum experience as great or one in which they wish to engage.

It is time to create exciting new ideas, values and practices aimed at increasing the relevance of art and art museums to rapidly changing audiences. Traditional interpretive, installation, exhibition and programmatic ideas and practices are not working.

Our mission at PEM is to create experiences of art, culture and creative expression that transform people’s lives. We have long acted on the belief that innovation and creativity are essential to making art and art museum experiences more meaningful and relevant. Following are some of the creative initiatives we are currently pursuing.

PEM is the only art museum in the world that employs a full-time neuroscientist to identify and apply neuroscience research to the design of art experiences that are more fully aligned with the ways our brains work than many standard kinds of art museum experiences. We are working to abandon the outdated 19th-century “Visitor/Attraction” operating paradigm for art museums and replacing it with a 21st-century “global community of communities” operating paradigm. We are creating a new financial model by dramatically increasing endowment to assure long-term financial security and to support increased innovation. Learning how to tell stories is a major new interpretive strategy.

We are under no illusion that these or other PEM initiatives are “the” answer to making art museums more relevant. We have, though, demonstrated that very ambitious goals, new ideas and practices, and intense focus on visitor experience can drive dramatic advancement and greatly increase attendance.

In today’s environment, best practice at art museums needs to be defined by innovation, creativity and experimentation. Opportunities to make art and art museums more central and influential parts of American cultural life have never been greater. All we need do is experiment and create new ideas, new experiences and new values that align with the interests, values and expectations of the expanded audiences we wish to serve. We are entering a new and exciting era, an era that will see art museums become far more popular, influential and relevant than they are today if we are willing to embrace and create change.

Dan L. Monroe is the Rose-Marie and

Eijk van Otterloo Director and CEO of the

Peabody Essex Museum.

Peabody Essex Museum

Salem, MA

pem.org

Why Collect? the Enduring (and ever-evolving) Importance of art

for campuses and communities

Anne Collins Goodyear and Frank H. Goodyear

With an etymology rooted in Latin and Greek, museums are “a place holy to the muses,” referring to those nine goddesses—daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Memory) associated with the arts and sciences. Today’s museums emerged from Kunstkammers, or cabinets of curiosities, established during the Renaissance, a period when new trade roots opened, systems of religious belief were questioned and unfamiliar objects from around the world sparked inquiry and the desire for study. Notoriously unwieldy and unpredictable, works of art tell stories. Their significance within museums today is less about conferring status than about challenging the status quo. In an era of uncertainty, like our own, characterized by questions ranging from matters of personal identity to the nature of truth itself, art prompts discussion, particularly within the context of institutions of higher learning. The arts remind us that no issue can be understood from one perspective and that, all too often, real understanding means the ability to entertain conflicting interpretations of “facts.”

Originating in the later 18th century, academic galleries represent our nation’s earliest collections, anticipating the founding of many municipal museums, an activity that flourished in the second half of the 19th century, in major American cities. Bowdoin College has been stewarding art collections for more than 200 years. In 1813—seven years before Maine became a state—the college’s founding patron, James Bowdoin III, bequeathed 70 paintings and 141 Old Master drawings to the fledgling academic institution. While many of the works collected by Bowdoin and his family represent an appreciation for such Renaissance masters as Raphael, Perugino and Salvator Rosa, others, including Gilbert Stuart’s portraits of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, reflect his ties to the pathbreaking democracy taking shape around him. Like Jefferson, Bowdoin recognized the importance of art as a source of education and inspiration for the citizens of the new republic. This tradition remains significant to this day.

Like most museums, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA) continues to expand its collections through the generosity of more recent collectors and benefactors. Yet, like others, only a small fraction of the 25,000 works in our care can be exhibited at one time. This prompts us to think hard about the essential question: Why collect?

Museum collections not only capture stories from the past and provide evidence of the emergence of new artistic concepts and styles, they also demonstrate the ways in which the meaning of art objects may shift over time as new contexts develop around them. A case in point is to be found in the BCMA’s five limestone reliefs from a royal palace in Assyria, donated in 1860, which provide an invaluable lens for understanding the ancient Assyrian past and serve to foster wider discussions about issues related to cultural patrimony, especially in light of international conflict in the Middle East.

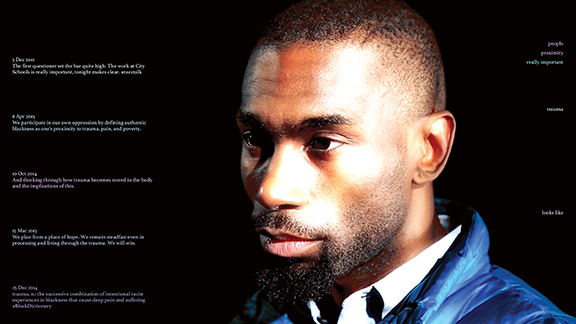

By a similar token, we are especially interested in adding new works that permit interactive exchanges between a wide spectrum of people about relevant contemporary issues. A recent example is 32 Questions for DeRay Mckesson, a 2016 time-based portrait of the acclaimed political activist by New York artist R. Luke DuBois. At its heart is a series of questions that Bowdoin students generated and that DuBois posed to Mckesson—a Bowdoin alumnus—during the filming of the work. The resulting generative video allows one to contemplate the formative role of a liberal arts education, the exercise of influence, the unfolding history of the Black Lives Matter movement and the emergence of social media that have played a critical role in shaping political consciousness in recent years.

Works that add complexity to existing historical narratives are also vitally important. The BCMA’s acquisition last year of a late 19th-century painting of a Sun Dance ceremony by an unidentified Lakota artist is exciting both because it broadens the range of artists and traditions represented in the collection and because it reshapes how we look at previously collected works of this period. Placed next to non-Native representations of Plains Indians or of lands in the American West, this painting prompts new lines of inquiry about the history of art in the United States that cross traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Collecting enables teaching museums such as the BCMA to further a commitment to equity, inclusion and the common good. It similarly allows us to bring together bodies of materials that have the potential to shape our understanding of transformative individuals through the work they produced or encouraged. One such recent acquisition is the archival collection of Marion Boulton (“Kippy”) Stroud and the Acadia Summer Arts Program (ASAP) she developed, bringing together an international group of leading artists and arts professionals, including Dawoud Bey, Cai Guo-Qiang, Ann Hamilton, Roni Horn, Alfredo Jaar, Sharon Lockhart, Abelardo Morell, Alison Saar, Carrie Mae Weems and William Wegman. Works by these artists and others will provide lasting insight into the vital contributions made in Maine to the visual arts in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. By the same token, the BCMA has also been fortunate enough to receive a major collection of artworks by Walter Pach, a committed modern artist, curator and scholar who not only helped to organize the Armory Show of 1913, introducing European modernism to America, but who also helped bring to international audiences the pioneering contributions of the Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. The drawings, watercolors and paintings by Pach reflect the important role of art-making for an artist who clearly sought to comprehend and communicate new modes of artistic production visually as well as verbally, as manifested in his prolific writing about modernism.

The BCMA embraces its obligation to share these historic collections with audiences near and far, and thus strives to make its holdings available not only in person, but also through digital resources, which are ever-evolving and further refine our ability to build new knowledge.

Why collect? We collect not to identify answers, but to stimulate questions. We collect so that the masterworks of creative artists from around the globe and throughout human history may continue to enlighten, to inspire and to provoke generations to come. We collect to connect.

Anne Collins Goodyear and Frank H. Goodyear are co-directors of the Bowdoin

College Museum of Art.

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Brunswick, Maine

bowdoin.edu/art-museum/

Authentic relevance:

Mining a Legacy

Peggy Fogelman

When visitors arrived at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum for a free evening of festivities in the summer of 2017 as part of our Neighborhood Nights initiative, they were greeted outside by a group of dancers on stilts clothed in flowing red brocade garments (designed by Gardner artist-in-residence Laura Anderson Barbata), accompanied by a procession of zebra puppets and serenaded by bongo-wielding drummers. Stilt-walkers, step dancers and music makers from local community organizations and schools added their artistry to the outdoor party, which attracted scores of visitors on a balmy summer night. Indoors, art activities, gallery programs and performance filled the spaces of the museum.

Born in Mexico City and based in New York, Barbata focuses on participatory projects that celebrate communities and traditions, using

art as a platform for social change and protest.

She first came to the museum as an artist-in-residence in 2006, one of a long line of artists in this 25-year program that continues Isabella Stewart Gardner’s legacy of patronizing creative practitioners of all disciplines and catalyzing new work. In 2007, Barbata began working with the stilt-dancing Brooklyn Jumbies Inc., who use performance to spread cultural awareness of the African/African-Caribbean tradition. Together they highlight the vitality of stilt-dancing and work with youth to, literally, rise above the difficult circumstances of today’s urban environments.

Barbata has a passion for fabrics and uses them to blend art, dance, music and performance into the costumes that she creates. When she returned to the Gardner for a second residency, she became fascinated with the Raphael Room restoration project then underway and took inspiration from the room’s textiles. The Raphael Room holds a breathtaking range of objects arranged in a manner both unique and confounding. In addition to the spectacular portrait of Count Tommaso Inghirami by Raphael and Botticelli’s theatrical representation of the Story of Lucretia, among other masterpieces, one finds a 1st-century bronze belt buckle from the Caucasus, an 18th-century priest’s chasuble, a beautiful inlaid guitar and a vase of dried thistles. Recently refurbished and restored after careful analysis by the museum’s curators and conservators, the room also now boasts 11 different silk and velvet wall coverings (all rich and varied shades of red) with tassels and fringe bordering each of the archways overlooking the central courtyard in a “more is more” aesthetic.

The approach to the installation, especially the absence of object labels, differs from that of almost every other museum in the country where many, if not all, the objects are installed according to region, period, medium or type. There was, however, a method to Isabella’s madness. In a painting by the lesser-known Renaissance artist Cima da Conegliano, the Virgin lovingly cradles the small foot of the infant Jesus while nearby, atop an inlaid wooden nightstand, sits a marble foot, perhaps a fragment of a larger Renaissance sculpture. Such conversations between works of art of different media, origin and even value abound in all the galleries and belie a faith in each viewer’s ability to make connections and find individual, personal meanings, regardless of background or previous art historical knowledge. Gardner’s conception for her museum was driven as much by the desire for emotional response as by the ambition to educate.

The well-known restrictions of Gardner’s will, which forbid the trustees from permanently changing the installation or adding to the fine art collection, can be considered her attempt to preserve the distinct nature of an aesthetic experience. Yet, they can also engender perceptions of stasis. While other museums with permanent collections do not, as a rule, reinstall them from scratch on a regular basis, public perception nonetheless distinguishes between the unchanging arrangement of the Gardner and the curatorial approaches to permanent collections in other museums. When we explore the issue of relevance and the need to demonstrate how the art of the past can speak to the audiences of the present—an issue essential for all American museums—the entire Gardner museum identity, as a holistic work of art with a singular curatorial vision, is at stake.

When Gardner dedicated her museum “for the education and enjoyment of the public forever” she knew full well that the public was not confined to the rarefied society in which she circulated. At the turn of the century, the city of Boston was not so unlike urban centers today: 35 percent foreign born, poor school systems, inadequate city services and health care and widespread economic disparity. Certainly, it is important to acknowledge that Gardner, coming from an elite background, was prone to the biases and class hierarchies of her day. Yet she was also personally involved in education and enrichment for Boston’s immigrants, partnering with community organizer Meyer Bloomfield to establish a tenement gardening contest, for instance. She held fundraisers and exhibitions to support refugees, disaster relief, disabled veterans and child welfare agencies. Her desire to establish the museum, in fact, derived from her belief that the young country of America needed experiences of beauty, and her collection would be a significant contribution to its development.

Equally central to her conception, and as little discussed as her progressiveness, was her understanding of the aesthetic experience, of which she left little explanation. Unlike Albert Barnes, founder of the Barnes Collection in Pennsylvania, to whom she is sometimes compared, Gardner did not aim for a particular pedagogical outcome. She did, however, aim to create multisensory, immersive environments and intimate, domestically scaled contexts for viewing the art. And by patronizing the artists of her time and providing a platform for live events of every kind—from classical symphonies to African-American spirituals to the cutting-edge dance of Ruth St. Denis—she turned the palace itself into both artwork and performance.

The Raphael Room restoration afforded the museum an opportunity to put this legacy into practice, building upon the innovative programming and audience outreach developed before and since the opening of the museum’s Renzo Piano extension. By commissioning an artist like Barbata, whose passion for both textiles and social practice align perfectly with the aesthetics of the Raphael Room and the museum’s ambition to meaningfully engage with its communities, the block party on that August evening offered an illustrative example of authentic relevance. n

Peggy Fogelman is the Norma Jean Calderwood Director of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Boston, MA

gardnermuseum.org