Experience Economies

Founded in 2010 by Gavin Kroeber and Rebecca Kate Uchill, Experience Economies is an event-based art series presented at unique sites throughout Boston. Experience Economies supports work by an array of artists and cultural producers, working across the visual and performing arts, the sciences, and the humanities. Not a lecture and not a party, Experience Economies welcomes experimentation, works-in-progress, audiences that want their spectacles to mess with them and presenters who need a space to make that mess.

Interview

RM. Guide us through the thought process that led the two of you to formulate the ideas behind Experience Economies.

RKU: We actually started with the idea of doing a potluck series of meetups for our friends and colleagues. The idea was that we might feature presenters who would take advantage of a forum where the audience might operate not just as critics but also as compliant participants in art experiments. We called the first event Stockholm Syndrome, for reasons that Gavin will detail. Our title was perhaps more titillating than we intended. Our invitees kept calling to ask what kinds of bondage, etc.; they’d be subjected to. We decided to start off the evening with everyone in blindfolds mostly because that seemed to be the kind of experience that people wanted, but it turned out to be a much more functional device than we had anticipated. The second part of our evening took the shape of a dual-lecture—we each gave a separate but simultaneous presentation about what we wanted the series to accomplish, speaking at the same time in front of one slide show. Our presentations were conveyed out to the audience through headphones at each seat— so people could choose whether to listen to Gavin in one ear/channel, or me in the other, or to attempt to hear both. I thought this would be a great way of demonstrating our own distinct internal positions on the politics and economies of experiential art. The other very important effect, in my opinion, was that this device served to fragment audience experience—at the time I was very interested in resisting the claims to a commons that sometimes accompany participatory or social practices of art. I liked the idea that the spectators would all be in the same room, engaged in the same activity—sort of—but clearly not having witnessed the same lecture necessarily. The blindfolded cocktail party ended up serving the purpose of focusing the audience on the aural, instead of the visual, which some people found useful as a preparation for the earphone cacophony that ensued. I find that especially interesting given the work that my advisor, Caroline Jones, has done on the modernist compartmentalization of the senses, and her current work which focuses on how the cultural and political imperatives of the contemporary art world invoke both the utopianism and marketing potential of “experience.”

GK: It’s interesting to be asked about how we formulated Experience Economies. In many ways I feel that the project has its own distinct identity and that much of our collaborative work has been less about engineering the series than about recognizing what “it” wanted to be. That said, and as Rebecca’s response shows, many of our original considerations are still very much at the core of even the most recent events. At the outset, I would say two key notions for me were what might be called “audience-as-material” and “event-as-form.” Both of these related to my practice and the research I was then beginning at Harvard, but honestly the early emphasis on these was a practical and instrumental thing. I had just arrived in town and hoped Experience Economies might be a way of quickly building a network—as Rebecca mentions ExEc was in its earliest formulation more a social series than anything else—and the question as we started was about what might magnetize the project, make people want to be there. We were paying out-of-pocket and the hope was that while we couldn’t provide presenters a stellar budget we could cultivate a willing audience—people coming with the expectation that they were going jump through some hoops—and that this is was something Experience Economies could offer as a resource for experimentation. The idea was not to wave the participation flag (which often marks the issues around commons Rebecca raises) so much as to highlight the control aspect – the audience would constitute itself as willing material, each attendee understanding that they might well be the one running the show next time. We named the first night “Stockholm Syndrome” to hyperbolize this idea —identification with your captor (plus Patty Hearst made for a good jpg). This kind of proposition dovetails with the “event-as-form” idea, which in shorthand simply had to do with addressing the entire arc of an evening as an artwork, presentation or structured experience, rather than just what happens on-stage or in the appointed moment of participation. The first event to a degree modeled this and when we began inviting other presenters to do something we offered the entire evening to them, asking them to propose a structure or a logic for people to follow from the moment they came in the door (maybe even before).

RM. The US military, as part of its counterinsurgency strategy in places like Afghanistan uses various non-military experts to “map” the human terrain for intelligence, and sometimes cultural purposes. Is there an element of “mapping” in your work?

GK: If Experience Economies provides a map of anything, it is of our own opportunities. Especially for the first three or four events, we were working with what was close at hand – spaces we had connections to, presenters we knew personally. As a side project for both of us, ExEc was very much about quick assembly, fluidity, and ease. With everything else we were doing, it could only work as an organic process, with a trust in each other’s instincts. We now talk about this as a logic of opportunism, and arguably it is one of Experience Economies’ founding principles. So, in a way, you could say that those early events mapped something of our social position. Equally, or maybe as a part of that opportunism, ExEc in those first couple rounds was for me about meeting people and getting my feet wet in a wider Boston world than what Harvard offered. I don’t mean to overemphasize the “Experience-Economies-as-networking-tool” angle—it was not my only motivation—but the project did serve as a way of orienting myself in a new city, and so there is a certain kind of map metaphor there.

That said, our two most recent projects have inclined towards mapping in a narrower sense. For Tania Bruguera’s visit we worked hard to get at least a bird’s eye view of immigration in Boston—who was doing activist and service provision work, where, and around what issues. Likewise we billed our last event, Innovate or Die, as a “tour of Boston’s innovation landscape,” so there was an explicit interest there in defining a kind of spatial typology. I don’t want to misrepresent these efforts, though—neither were thorough mappings (intensive as they might have been for short periods of time). They were starting points. Our project timelines have stretched compared to our first events and our planning has become much more precise, but we’ve still been tackling these projects on far shorter and more distracted timelines than most institutions would, and we’re under no illusions as to how comprehensive our research has been. We both do research in other capacities, Rebecca in particular, and our ambitions going into these projects are quite different. But, then again, maps are rarely about the “thoroughness” of research so much as making a geography pliable for use, whether that means the extraction of natural resources from a landscape or, in our case, identifying collaborators and material for cultural production. Most maps are complete as soon as they’re functional, regardless of what they leave out. Our surveys have been at least sufficient, so maybe they do constitute “good” maps.

I should also add that I feel that we’re now at a kind of transition point with Experience Economies. The more recent events were quite different from the early ones, and likewise I don’t think future events will be assembled in quite the mode that Tania’s project or ExEc 6 were. All I mean to say is that the kind of approach I’ve started laying out here is hardly a cornerstone method, but more a matter of how we worked at a given time in our evolution.

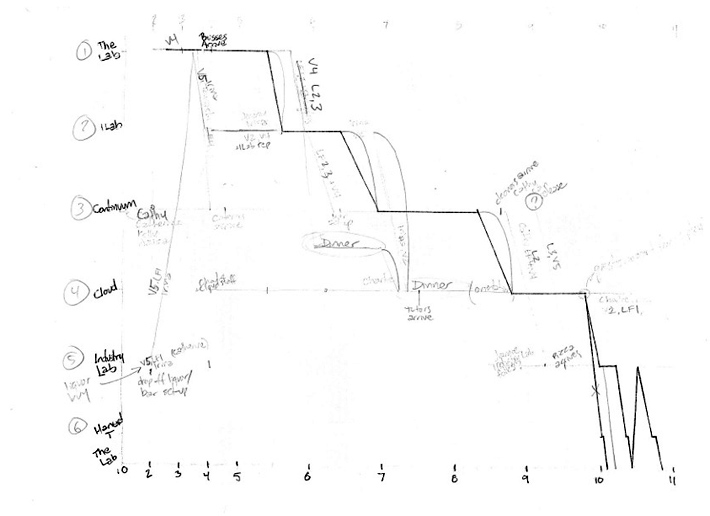

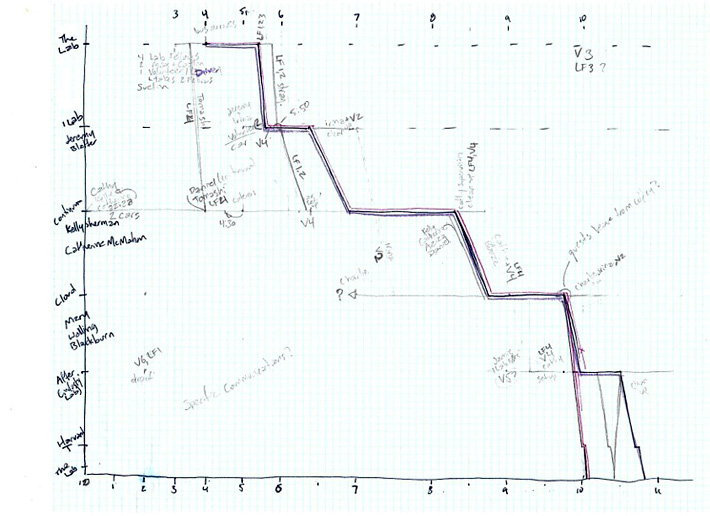

RU: I’d only add that in each of our projects we map time extensively with run-of-show documents, graphs that chart audience spatial movements, atmospheric trajectories, and technical cues against each other, and other kinds of tools/maps (we are going to track down a particularly good one to send to you).

RM: Interesting. This idea of a networking tool is exactly what the military has in mind (when they aren’t burning the Koran) when they “map” an area. On a fundamental level, they want to get to know people, who they are, what they do, and possibly, how they may be of help. Or conversely, who might want to kill them. From a generational perspective, the idea of networking is now mostly an electronic one. Yet, most of your projects involve more traditional interactions. Is that intentional? Is the idea of personal “contact” intrinsic?

RKU: Well, it’s really exciting to be compared to the US military, but there are a few significant differences, including the fact that we haven’t declared war on anyone, though neither are we claiming to be keeping the peace! Sociability and “constructing the audience” have both been themes we’ve explored in our work in Experience Economies and elsewhere (I have an article that just came out in the Journal of Curatorial Studies that looks at strategies of exclusion and alienation as means of probing the very idea of the discursive commons). From ExEc 3 onwards we’ve been pretty attentive to who is attending our events, making efforts to reach out to broad and/or targeted groups. For Tania Bruguera’s project this included a roundtable conversation including Kyle de Beusset and other members of the Student Immigration Movement, MacArthur Fellowship-winning economist Michael Piore, Villa Victoria curator Anabel Vasquez-Rodriguez, immigrant artists living in Boston, and community organizers. It also included a closed-door workshop at ROCA in Chelsea, which included young adult immigrants, led by Victor Jose Santana. For the Signet Society project, we were sensitive to the politics of cultural and other exclusion that surrounded that space. We reserved a block of tickets for Signet members, but made sure that a larger number of tickets were blocked out for non-members. We then made an effort to make the place strange for those audience members who use it as their clubhouse, redirecting the flow of traffic and changing the usual rules of the space. A project by Tomashi Jackson and John Hulsey pointed directly to the ways that power leverages exclusivity, with a room that had a sort of arbitrary entrance policy—the reward for entering the room was being led in songs celebrating artificial scarcity. In the most recent project with The Lab at Harvard, we had a staggered series of ticket releases and a complicated algorithm for bringing people in from the wait list, in order to preference a diversity of backgrounds (art/science/tech/academic/corporate/college student groups, etc.). We also stacked the two buses to make sure that each bus had a range of audience participants aboard.

GK: Networking, for me, actually has a connotation of copresence. You’re right, of course, that there is a lot of ‘networked networking’ going on, but to me it is a word that stands for very specific face-to-face practices and physical artifacts—handshakes, small talk, elevator speeches, business cards, think of the networking sessions that are on the day’s schedule at a convention or that (as far as I can tell) define the lives of students at the Harvard Business School.

The convention and the convention center are actually important figures in my thinking around Experience Economies – and around the so-called ‘Experience Economy’ from which we took our name. Conventions are very much the intensive, tight-packed flip-side to the sprawling networks of communications technology and globalization, this mechanism for doing business that has just exploded since the seventies and the end of Fordism. There’s a lot of writing in the business world about how face-to-face working is more productive and face-to-face sales more profitable, and so conventions become this kind of engineered hyper-encounter that can maximize these benefits, and the convention center becomes this amazing logistics landscape, like a distribution center for people. So, you have businesses and trade organizations competing to produce the most attractive conventions (and the most attractive booths within them), and simultaneously municipal governments (ostensibly hungry to attract spending attendees but also to a great degree guided by industry lobbyists) competing to create the most attractive convention centers, which is an effort that often extends beyond the center itself and into the attractions of the district around it. On all these fronts—from the booth to the city—the idea of structuring experience for a live, face-to-face client is primary.

This is just one example, of course, of how live encounters are being put to work. I have a background in the performing arts, where there’s no end of hand-wringing about what makes the live event special and might keep it significant, and therefore no end of romantic claims made about it. This always feels a little funny to me, because in more or less every other cultural sector we are left and right dealing with an investment in and proliferation of live events and experiences. Significance hardly seems to be in question, and moreover they start to feel less and less special; in fact, downright ordinary.

So, for me I am interested in what makes a “traditional interaction” work on a level of structure or ritual and the attention we give to our audiences is a big part of that, but I am also interested in what makes the well-oiled traditional interaction so damn ubiquitous. I think of our work to date as a series of experiments or investigations made at both these levels, the discrete event and the larger context (or, I guess, the experience and the economy).

RM: Interesting that there is a desire to curate both the content of the work and the audience. Someone, say, like Marina Abramovic, will leave the audience to the museum ticket-sellers. Demographically speaking, she sort of knows the “type” of audience she’ll get anyway yet her work is there for the price of a ticket. Understanding that, is there a danger that this all gets too incestuous, all too hung up on an elite orbit?

RKU&GK: (In unison) Yes.

RM: And then what? Or, perhaps, is that the trick itself? I mean, there isn’t much sense in launching a satellite just above the treetops, is there?

RKU: I don’t want to overemphasize our attention to the audience constituency, but it is a consideration. Two of our events in the last year sold out in under five minutes (Suelin Chen, the Director of the Lab at Harvard, compared us to U2). In both of those cases we made a point of ensuring space was available to attendees we’ve never met before and particularly folks from outside of circles of art practice. I was gratified when three men approached me at the Innovate or Die after-party to congratulate me on producing such an amazing event. It turned out they hadn’t been on the bus tour we led, they were just really digging the range of people they met at the party!

GK: I do love these kinds of moments, where the “mix” of attendees strikes a chord, but it should be said that they are precisely the product of exclusivity. We make an effort to include people outside of our immediate circles, but this is hardly an act of radical inclusion. It is a very particular or even targeted inclusion. For Tania Bruguera’s project, for example, we were reaching out to potential participants engaged with immigration issues, or for Innovate or Die to product designers, engineers, entrepreneurs and scientists. This may open the event to a degree, but it still takes place inside a pretty tight boundary.

When drawing this boundary—as in many other equally important decisions that are made as a project is developed—the primary consideration is the logic of the particular event. We’ve always started from event making, and the emphasis is on serving the project rather than any institutional fact such as an anticipated public or a given architecture. I don’t want to exaggerate this—we do have a mailing list, a core audience, even some regulars, and likewise we have both by taste and by circumstance engaged only certain projects that we felt it was feasible to work with in this way—but our nomadism and our small scale have allowed us in large part to give over to the event what in many other institutional situations would be more rigidly predetermined, be that a location, an audience, a style of encounter, or a structure of time. That has very much been at the heart of this experiment.

RM: Defined then, as an experiment, has there been a break-through moment, an epiphany…? Or has there been a progressive series of smaller insights?

RU: I’m not sure our project should really be defined as “an experiment” so much as “experimental.” To me this means that we are exploiting our unencumbered status as a “mockstitution” to take on projects/chase down directions that are interesting to us, even when they seem risky or strange or perhaps likely to lead to dead ends. So, for example, we have been able to throw ourselves into the ambiguities and problematics of pointing to a number of ideas at once, where another type of project might require one to be more essentialist or politically articulated… For example, our eyes are wide open to the notion that we are culturally enmeshed in this series of entanglements that we call “Experience Economies”—with our series name taken from a Harvard Business School book by the title The Experience Economy—without necessarily embracing the full spectrum of politics or ethics that might be associated with that position.

GK: Yeah, the “experiment” I refer to is really just “Hypothesis: Gavin and Rebecca can work together without driving one another crazy and people will show up.” But within the broader experiment of our collaboration the ideas and methodologies I was raising have very much been in play. I’m coming to think of Experience Economies as a platform – a kind of space or structure that we’re clearing or building that allows us to tease out different interests in event-as-form, structures of experience, and modes of attendance within discreet, bounded events as well as through the production of discourse or proposals. I, for example, as someone who has a relationship to both “black box” experimental theater and “white box” visual arts performance, am interested in exploring how a category like “event” might serve to reconfigure the often antagonistic disciplinary relationship between those traditions. As this series continues and the events pile up into an aggregate or a narrative it begins to compose a kind of proposition, or at least a material from which a proposal could be made. Though that capacity of Experience Economies was there from the beginning, it is only emerging as something more concrete now, as we hit a certain critical mass of projects under the belt. This interview facilitates that emergence, in fact.

RM: There are parallels here to a business model, an entrepreneur’s vision of how a narrative is shaped. Is there any difference anymore between the commerce of ideas and the transactional world of goods and services?

GK: I think it is hard to deny that there’s a convergence, but the question is whether that convergence is total (in which case one term or the other would be rendered redundant) or specific (meaning happening only around particular people, places, ideas and kinds of transactions). It seems likely that what is sometimes perceived or celebrated as total in fact represents many different convergences between these very different economies, taking place around specific sectors, actors, circumstances, and intentions.

So, on the one hand, we’ve named ourselves after a book published by the Harvard Business School. This goes back to Rebecca’s point about being transparently enmeshed. On the other hand we pluralized the title, and as the project has picked up steam that has become quite important for me. The pluralization suggests the possibility of producing different, varied articulations between the conceptual and transactional worlds you ask about, around specific people, places, economies. Event-based work has a potential to provisionally reconfigure the relations between sectoral and social formations in a way that a brick and mortar institution might not be able. I think this is what has made Experience Economies meaningful for us – teasing out the different and sometimes conflicting potentials of event-as-form, attendance, experience, nomadism.

RM: Moving forward, what’s next for Experience Economies?

RKU: We have an idea that will involve a trip further afield later this spring, and over the summer we also are going to do a small workshop at Mildred’s Lane, an artist’s compound in Pennsylvania, as part of a session called “Town and Country” led primarily by the artist and educator Pablo Helguera. Beyond that it’s hard to predict. From the outset this has been a project that’s followed its own logic and direction. The events changed form and scale depending on the kinds of invitations we’ve received, the people we were working with and the ideas we collectively wanted to tackle. In this way this side project hasn’t just been a necessary distraction from academia for two grad students, it’s also been a test site for considering applied ideas (What does it mean to rigorously produce the form of an event? What would ensue if we were to structure the audience in different ways? In what ways can we confront, head-on, the weird entanglements of entertainment industrializing-meets-artistic dematerialization-meets-post-welfare-economics of the art institution?). The Experience Economies series has also been a great platform for meeting people, developing collective ideas, getting to know the city, and so on.

On a personal note, it’s been really wonderful for me to have Gavin in Boston these last couple of years. I feel very lucky that we have a great working trust and chemistry, and I don’t think that Gavin moving back to NYC will mean the end of the project altogether, but it may lapse in its regularity, and the format will definitely continue to evolve.

GK: I can only second that. It’s been a remarkable and surprisingly organic collaboration and one that has helped me refine my thinking about my practice independent of ExEc. I don’t have a crystal ball but it does feel to me like we have had the privilege of laying a foundation here that we could continue to work from even when I leave town. I’d add to that, too, that I do harbor some hopes that there will be chances to work in Boston again as well as further afield. I’ve come to know this city in many ways through this project and that process would feel somehow cut short if there we no opportunities to return to the particularities and contradictions of his place that are only now becoming clear to me.