Four New Artist Residencies

Indigo Arts Alliance

Portland, ME

indigoartsalliance.me

Carl Little

When Marcia and Daniel Minter moved to Portland in 2003, they had their doubts. Maine was said to be the whitest state in the U.S., and it was cold. But the welcome the couple received and the ensuing evolution of the city into a more diverse place, culture-wise, brought them around to where they are today: proud founders of Indigo Arts Alliance, a new residency program dedicated to cultivating the development of artists of African descent.

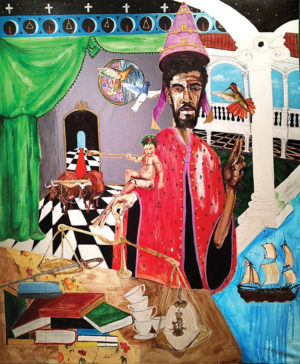

The space opened this past May on Cove Street in the East Bayside neighborhood. The building features flexible workspace, plus two studios, one for a visiting artist, the other for Daniel Minter. A painter and children’s book illustrator, Minter has been working on a series of paintings and mixed-media work related to the infamous removal of a mixed-race community on Malaga Island off the coast of Maine in the early years of the 20th century. His studio is brimming with new work.

The flexible residency is set up as mentor-mentee collaborations. For the first two years, the resident artists will be chosen by an advisory group, with an open application process instituted thereafter. The first cohort over the summer included Fo Wilson, an artist/designer, educator, independent curator and writer from Chicago; Eneida Sanches, a visual artist from Bahia, Brazil; and Ebenezer Akakpo, an artist-designer from Ghana.

The alliance works carefully to match the resident artists. At the same time, says Marcia Minter, “as citizens of the state of Maine and New England,” they are committed to amplifying the practices and leadership of professional artists who are “black and brown and coming from different parts of the world so that they have the benefit of cultivating new relationships with organizations, institutions and individuals here in Maine.”

One of this fall/winter’s residents, Asata Radcliffe, a writer, multimedia artist and adjunct professor at the Maine College of Art, is researching African American soldiers who guarded train stations in Maine during World War II. She stumbled onto this piece of lost history in the Monson Historical Society during her stay at Monson Arts, another new Maine-based residency for artists. Based on her discoveries, and with support from a Maine Arts Commission grant, Radcliffe is organizing a show to be mounted at the Maine Historical Society during the state’s bicentennial in 2020.

Radcliffe is mentee to Pakistan-born documentary filmmaker and textile artist Sarah K. Khan, who has lived in New York for the past 20 or so years. It’s a great match: Khan is also a documenter, teacher and maker who shares a common mission: what Radcliffe calls “defying erasure, digging into histories and making sure they are surfaced and celebrated and archived.” The two are in and out of each other’s spaces, sharing ideas.

The history Khan is exploring started with a Farsi text and her discovery that there was an African presence in India millennia ago. She is retelling the history through the lens of the Africans and Indians who worked together—and by way of her ongoing focus on food studies. She is creating a cookbook based on her research, with plans to hold a community dinner during her residency. Portland printmakers David and Sean Wolfe will print the woodblocks for the publication.

Several partnerships have formed since Indigo Arts opened. One of them is close by: the alliance and Cove Street Arts across the street have collaborated on several projects and programs, including an exhibition curated by Marcia Minter featuring the international photography of two Maine artists, David Caras and Meredith Kennedy, and a talk by Daniel Minter and the scholar Henry Drewal about the former’s Malaga series.

The alliance has also connected with the Maine College of Art. Their intern this fall, Alejandra Cuadra, is a MECA student, her internship supported by a grant from the Crewe Foundation. The grant also helps cover the residency of a recent MECA alum, textile design and fashion artist Jordan Carey, who is working with Meeta Mastani, a master printmaker from India.

Marcia Minter, who is currently transitioning from her position as creative director at L. L. Bean to full-time director of the alliance, calls the alliance “the fulfillment of a dream” she and her husband have had for many years. “We’re trying to be a part of an international story around enabling and amplifying the practices of black and brown artists,” she states. So far, so great.

___________________________________________

Carl Little lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

77ART Artist Residency

Rutland, VT

77art.org

B. Amore

Ascending the wide staircase of Rutland, Vermont’s historic 1882 Opera House, one is surrounded by a circle of glass-walled studios built into the once-gracious balconies. Rachel Spitzer-Firliet, a resident artist, is creating a beehive of wire and wax, a metaphor, it seems, for the buzzing studios that now inhabit the building.

The 77ART Artist Residency is the brainchild of founder/director Whitney Ramage who was inspired by her own 2016 residency at the Studios at MASS MoCA. Ramage believes that residencies are a means of moving ideas around the globe. Her 77ART residency, in particular, asks the questions: Can we improve our community simply by giving it access to artists? By bringing working artists from around the world to this microcosm of American society, can we introduce new points of view in an inviting and inclusive way?

In its inaugural year, the 2019 77ART residency in June, August and October welcomed 42 artists from all over the world and major cities throughout the U.S. The residencies are financed by a mix of modest tuition from participants, with studio and housing donated by Mark Foley Properties, and community-donated food. Residents live in a group boarding house around the corner from the Opera House. They often cook for each other in the communal kitchen, have living room dance parties, late-night studio gatherings and group trips to the farmers market. Lunches, provided by community members, are a focal point of the day with studios open for visiting and discussion.

Many of the artists chose the residency because of its location in a post-industrial city. Rutland is a unique mix of a 19th-century architectural treasure surrounded by mountains. Everything is within walking distance with just enough urban grit to pique their interest. The Mint, a world-class makerspace, is part of downtown and Mint members have taught residents how to weld, use the laser cutter and CNC router.

The essence of the residency is work in the studio. Yet Andy Wellington, a painter, also prized the sense of community and dialogue, and reflected on the lack of a similar experience in his Bushwick, NY, studio building. His work centered on color studies while Liliana Dirks Goodman, in the next studio, created a 20-foot painting using a feminist form of “camouflage,” replete with floral components.

The collective presence of the residency pushed the artists to reach beyond their limits. Ben Hoagland explored adding text to his evocative paintings of boats. Amalya Megerman, recently returned from three years in China, extended her studies of intergenerational trauma into a performance. She created a “dress” out of bubble wrap injected with colored liquids. Like a Kabuki dancer, her motions were deliberate, repetitive and charged with emotion as she squeezed the liquid out of the bubbles while her studio mates provided the soundtrack by cracking nuts in the cavernous space which was once the Opera House stage.

Three sculptors, Blaykyi Kenyah of Ghana, Unu Sohn of Korean heritage and Adriana Gallo, born in Italy, integrated cross-cultural questions into their work. Having lived their lives between cultures, they were fascinated with the intersection of traditional ways of making art and contemporary adaptations drawn from their lived experiences.

Both Lauren Peterson from Colorado and Sam Ashford of Brooklyn often use detritus to create sculpture. Patterson created a monolithic form of ripped-up carpet from her studio space, layered over with party-like trimming. Hidden within it during her final performance, she surprised the audience by blowing up balloons and sending them on zany paths towards the audience. Ashford, a photographer and sculptor, calls his poetic self “an absent figure always present in the work.” Drawing from his collection of 30,000 slides, he created a Joycean journey by combining images and words in a form of illustrated poetry.

Ramage refers to this collection of residents as the “Deep Diggers.” A common thread of authentic question and search permeates all of their work, as it does Ramage’s own. Her exquisite exhibit, (DIS)EMBODIMENT, in the 77ART Gallery, combined sculpture, video, photography and drawing to explore how the human body relates and interacts with the world.

With weekly presentations of their work to the community, and a final sharing at the close, the residents are active participants in the Rutland Renaissance. The Opera House itself is a crucible of energy, and the buzz of creativity emanating from the central hive emanates in ever-widening circles into the surrounding community, and beyond as these artists travel on to share their work.

__________________________________________

B. Amore is an internationally exhibiting artist and writer. Her reviews appear in Sculpture magazine, VIA and the Times Argus/Rutland Herald, among other publications.

Joseph A. Fiore

Art Center Residency

Jefferson, ME

mainefarmlandtrust.org

Jodi Paloni

It’s summer in Jefferson, Maine. I turn right onto Punk Point Road and slow as I drive by a large shingled barn with a blazing red door, a yellow-green field, a peek of John Rice Brook meandering through the woods. Where the woods open, an engaging scene brightens. A farmhouse with an attached barn, a field beyond and more forest––133 acres on Damariscotta Lake’s shore–––comprises the Joseph A. Fiore Art Center at Rolling Acres Farm. The homestead and surrounds has been swept into the care of Maine Farmland Trust (MFT) to create a residency program and gallery event space in which the imperative of land stewardship merges with the impulse to celebrate art, attracting artists for whom relationship with the environment is central to their work. I slow as I pass through the portal of this place because place is at the heart of its mission.

Four years running, the center is named after Joseph Fiore, an artist and environmentalist who summered nearby and depicted the landscape in his art. His work is archived in a renovated ell between the house and barn studios. His paintings hang on the walls, here to inspire, as are the views of the field, the lake, the woods and the Maine summer sky.

I settle into the house. The downstairs hub is an open space—kitchen, living room, and farm table—winged by a gallery on both sides. It’s the heartbeat of the center, while the bedrooms upstairs provide a respite for three artists during the four summer months, and the gardener, Rachel Alexandrou, who is also a practicing artist living here for the season. My bedroom has a writing studio next door. I feel the presence of last summer’s resident, Sarah Loftus, Fiore’s first writer, selected to chronicle the history of the farm. Weeks before I came, I gazed on a farm tool sculpture Sarah made that hung in the MFT gallery in Belfast, ME, where an annual show is curated to highlight the work made by previous residents and build interest in the emergent season.

My upstairs studio boasts more of the long-range views, which I find pleasing and informative for writing about place, yet I’m drawn to immerse in the land, which is highly encouraged here. I turn an abandoned chicken coop at the crest of the field into a makeshift studio. A rough-sawn sill serves as my desk. It’s where I listen to the voices of fictional farmers, where I imagine stories about the growing pains of the people and this land as it was carved into lakefront lots.

Nearby, my fellow artists hole up in their barn studios. Maxwell Nolin, a young Maine painter, renders the portraits of local farmers whose forms and features help me in detailing my characters. Thu Kim Vu, a Vietnamese artist, is inspired by the bounty she sees outdoors. Here on commission to draw a cityscape of her home in Hanoi, Thu becomes enamored with heirloom vegetables. She draws pen and ink kitchen scenes on rice paper and mounts them on Plexiglas. The natural light coming off of the field lights a trio of transparent tablets hung by fishing line, stacked against her studio window. They become a pendulum-like moving picture.

Our schedule is measured by shared meals we create. Forage and garden harvest becomes the palette of our table. After supper, Rachel, a musician as well as a botanist, performs a folk song to accompany Thu’s sculpture in motion, while Max and I watch, delighted. In this way, an artist community is curated.

The community waxes with the growing season as guest artists visit and lean into our work, offer us wisdom from theirs, and share in a special dinner. We are labeled as painters, poets, printmakers or performers, but we are all telling a story of the land: how the bobolinks fledge as hay mowings are scheduled to honor their birth cycle; how weasels run through stonewalls surrounding the cemetery; how loons sing to the stars as we dream.

As the residency wanes, wild turkeys appear to fatten on seeds. When the last of the artists exit the portal in September, Rachel gives the compost heap a final turn, and makes a photograph about decay. Everything becomes still. I like to think that each visitor has left a legacy to enrich the tilth of next year’s crop, vegetables and artists alike.

___________________________________

Jodi Paloni is a freelance writer and the founder of Maine Coast Writers Workshops and Retreats based in Bristol, ME. She is the author of a collec-tion of linked short stories, They Could Live Themselves. Her MFA in Writing is from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Mabel Residency

Norman Bird Sanctuary

Middletown, RI

normanbirdsanctuary.org/art

Helena Touhey

The giant doors of an old clapboard beach house are open, replacing an entire wall with an expansive vista of sand, sky and the Sakonnet River beyond. September air permeates the space, filling it with a slight chill and hint of salt water. In each of three doorways a koinobori lantern sways in the breeze, bright colors accented against a mercurial sky.

The other walls of the spare structure are adorned with large paintings of trees, in colors of bright green, cyan and magenta that appear to mirror the koinobori. Near the center of the room stands a table wrapped in paper, forming the base of a makeshift workstation, displaying a collection of gray-tone shell images printed on small sheets of paper. On the floor there are more sheets of paper, showing ink wash sketches of landscapes, inspired by the shoreline and also a valley that extends behind the beach house.

The works belong to Lois Harada, one of a handful of artists participating in the Mabel Residency. Generally a printmaker, she spent two weeks experimenting with other mediums and deviating from her usual artistic process, exploring and creating from a makeshift seaside studio at the Norman Bird Sanctuary in Middletown, RI.

Situated in the heart of Paradise Valley on Aquidneck Island, the preserve is a nonprofit wildlife sanctuary and education center with more than 325 acres of diverse habitats and seven miles of hiking trails. For a few weeks in early September, the sanctuary’s structures, ordinarily used for camps, classes and retreats, were converted into artist workspaces as part of the Mabel Residency.

The preserve was once the home of Mabel Norman Cerio, an artist in her own right and the namesake of the residency, who lived and worked on the property from 1912 until her death in 1949. In her will, she requested the estate become a bird sanctuary with public access that would exist in perpetuity. A few buildings dot the property, from an old farmhouse to a big barn, an education center and a smattering of spaces now used for classrooms, and a string of old clapboard beach houses that stand near the shore. Many of these spaces are converted into studios for the duration of the residency, which marked its inaugural run last year with a pair of two-week stays that hosted five artists at a time.

Artists have their own room in a renovated farmhouse, joining the group for family-style meals, which are prepared by a local chef. During the day, participants retreat to their indi-vidual work spaces, which are adapted to suit their artistic needs, some situated near the shore, others along the woods. Everyone is encouraged to explore the property and take advantage of the trails and coastline, which are meant to inspire the work created during the program.

All mediums are welcome, and past artists have worked on paintings, prints, quilt projects, ceramic casts, choreography, musical compositions, sculptures, photography and video projects. Last year, all artists participated in an Open Studios at the end of their session, for which members of the public were invited to visit the sanctuary, tour the studios, view the work created, meet the artists and learn more about their process.

“I’m really glad to be here,” Horada said during her stay, “for the view, and also for

the artist group.” Usually busy printing at a letterpress workshop in Providence, she was happy for the time and space to work on her own projects and to create pieces inspired by her walks around the sanctuary.

Around the corner, in another clapboard structure, Anthony Goicolea had his laptop setup on a makeshift desk and was scrolling through photos taken that morning of lifeguard chairs on a nearby beach. “I’m in the process of making something from them, I’m not sure what. The fog was great,” he said, explaining that a lot of his work is inspired by nature and otherworldly environments.

A week or so later, during the Open Studios, Goicolea shared a slideshow of these images transformed: one by one, the chairs emerged and were layered together, forming an abstract interpretation of an ordinary beach scene, all the while taking the viewer through Goicolea’s morphing perspective. He told

those gathered in the darkened studio that this was a work-in-progress, which he planned to continue tinkering with once he was home, where the images were bound to evolve, perhaps inspiring other projects.

_____________________________________________

Helena Touhey is a seeker and collector of stories at heart, and a writer, editor and journalist in practice. She lives in Newport, RI.