Geometric Breathing

Jonathan Prince, Southern Remnant (at Christie’s Sculpture Garden, 535 Madison Avenue, NY), 2012, CorTen and high-chromium stainless steel, 60 x 132 x 60″. Photo courtesy of Melina Hammer.

A giant disk. An eight-foot cube. A monumental cone. Perfect geometries rusted by the weather, Jonathan Prince’s sculptures have the sense of something old and impenetrable. Until they rupture.

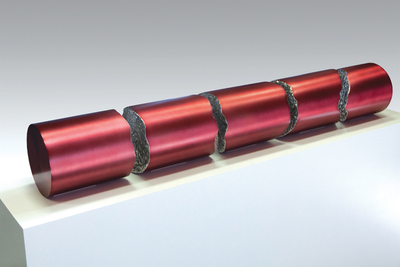

Many of his sculptures look as if a giant has come at it with a pickaxe and hacked a piece off. Inside that wound, shimmering stainless steel ripples like a slide of liquid mercury, winking in the light. It’s gorgeous, unpredictable, vulnerable and deeply alive in contrast to the rusty planes that barely seem to contain it.

“All the pieces have something broken,” says Prince. “The breaks can be beautiful, like the internal life we all struggle with and have to embrace.”

The sculptor has been on a roll, with public installations recently in New York at Hudson River Park, Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, Christie’s Sculpture Garden and an exhibition, Torn Steel, at 535 Madison Avenue Sculpture Garden. He’s had regular appearances at art fairs with Cynthia-Reeves Projects and several exhibitions. The most recent closed in October at the Helen Day Art Center in Vermont.

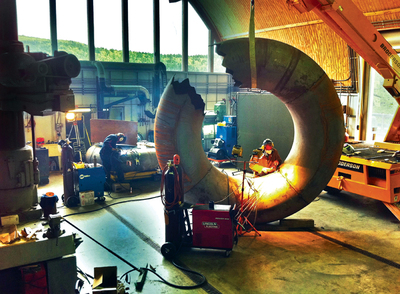

Above: Jonathan Prince Studio, fabrication of Torus 340 (foreground) and Disc Fragment (background). Below, t. to b.: Jonathan Prince, Liquid State (Inhale), 2014, high-chromium stainless steel, 24 x 24 x 24″; Jonathan Prince, Vertical Ingot (Blue), 2013, high-chromium stainless steel/transparent color, 50 x 10 x 14″; Jonathan Prince, Ruptured Column, 2013, anodized and colored aluminum, 8 x 53 x 8″; Jonathan Prince, Basin (Blue), 2014, high-chromium stainless steel, 6 x 16 x 16″. All images courtesy of the artist.

In 2012, Prince’s Vestigial Block was the first piece installed in the sculpture garden at Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, a gift to the museum from Edward Minskoff. The six-foot, rust-streaked cube breaks into a wide canyon of delicately variegated stainless steel, gleaming as it narrows toward a low corner.

By taking the formidable and exposing its innards, Prince assails the very idea of the monumental.

“There’s almost a movement in contemporary art now to dematerialize strongly material objects,” says the Broad Museum’s founding director Michael Rush, formerly director of the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University. “Jonathan is taking a solid, familiar form and saying, ‘Look there are many things potentially going on here. Let’s tear this open and look inside.’”

Despite their ravishing imperfection, every step of the way toward making Prince’s sculptures is one of spit and polish.

The artist lives and works in a converted dairy barn (two, actually, joined together) on the far side of the Berkshires. He shares his living space with his wife, Bridget Ford Hughes, a massage therapist and ceramicist; and two Greater Swiss Mountain Dogs, Maggie and Ruby. When a visitor approaches, the giant dogs defend the house with basso barks, but they’re secretly softies.

Prince’s studio is a lab for techniques such as welding, polishing, heating and shaping steel. Even rusting it. When I stopped in, the sculptor and two assistants were at work on an eight-foot cube—his largest yet—and on a smaller piece. Basin (Blue) is 16 inches around and six inches deep. Not all of Prince’s works are split open monoliths; this one is all stainless steel, smooth around the side but topped with a rippling, watery surface, which the artist intended to paint blue.

“We send our paint to a lab to test coherence to metals,” Prince says. “I want to set up my own techniques to get cohesion between the paint and the substrate.”

He steps into a side room and we peer through the window of a heavy door, like that on a vault, into a dust-free “spray room” where paint is applied. When he paints in there, “I wear a full-on Ebola bodysuit,” he says. “I don’t want to bring dust in with me.”

Works such as Basin (Blue) take 30 coats of paint and then get polished infinitesimally, resolving imperfections down to fractions of

a micron.

“We know when we’re done when every time we try to fix something, it’s worse than when we left it,” says Prince. “We know when we have pushed the limit.”

Despite all the technical refinement, chaos is inherent in this artist’s work. He even seeks it out. All those divots and crests in some of the stainless steel surfaces, for instance, result from a group process. A single artist tends to have signature gestures, and Prince doesn’t want anything to look predictable or repetitive.

Jonathan Prince with Torus 340. Photo courtesy of Star Black.

In his studio, Prince shows off several cubes surfaced only with stainless steel. How many ripples does it take before a cube is no longer a cube? Prince and his team go at that surface with flame, hammers and a hydraulic press.

Look at Liquid State (Inhale) and Liquid State (Exhale). They seem to puff out and contract, indenting voluptuously as they go.

“I liken them to breathing,” Prince says. “How much can you expand the breath within these forms?”

He is garrulous, passionate about explaining his work, his techniques and his philosophy. His mind is as capacious and busy as his studio. There’s a lot going on, yet there’s an intrinsic order to it all. Prince has always been able to keep a lot of balls in the air.

Sculpture is not his first career, but it is the one he always dreamed of.

He grew up on Long Island, the son of a dentist. The sculptor Jacques Lipchitz was a friend and patient of his father’s, and when he was a boy, Prince visited Lipchitz’s studio. The sculptor invited him to help out, and Prince applied clumps of clay to a monumental bust, which Lipchitz then shaped.

“He took a liking to me,” Prince says. “I thought it was the greatest job in the world—from a 10-year-old’s perspective.”

But he followed in his father’s footsteps and became a dentist, specializing in maxillofacial surgery. He did well, but yearned for a creative life. Other careers followed: film producer, special effects wizard.

In the 1990s, he designed the HoloGlobe, a digital vision of climate change displayed at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Natural History. He followed that with an Internet startup, overseeing more than 100 employees. It collapsed in the early 2000s.

“At that point, I thought, ‘I’ve had it. I’m now going to do what I’ve been afraid of and always wanted to do the most,’” says Prince.

He became a sculptor.

Not one to enter into anything lightly, he started with granite. His early works echoed the spare, lyrical abstraction of pieces by some of his heroes: Isamu Noguchi and Barbara Hepworth.

“It took me three or four years to get those 600-pound gorillas off my back,” Prince says.

He looked at Richard Serra, whose eight-foot cube Berlin Block (for Charlie Chaplin) dwarfed Prince; and the liquidity of Roni Horn’s big glass disks.

He began to think, he says, about “kinetic work that doesn’t have to move.”

That’s what his stainless steel does. Light flashes and plays off the surface. Reflections swim, jump and fracture. These works feel as if an old, inviolate geometry, governed by heft and gravity, cracked open like an egg, and something new poured out. And that makes them less imposing, more something a viewer is drawn to investigate.

G2V, a giant rusted disk with a glimmering, slippery wedge of stainless steel coursing within, was installed at Dag Hammarskjold Plaza for six months. The United Nations is nearby.

A green market is often held there.

“The site calls for large, monumental pieces. There’s the bustle of traffic, an imposing building across the street,” says Jennifer Lantzas, public art coordinator for New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. “Formally, Jonathan’s piece held the space extremely well.”

Just as important, people wanted to interact with G2V. “Everything about his works, you want to touch,” says Lantzas.

Part of the fun is the burbling reflections the stainless steel casts. Prince grants a certain kinship with Anish Kapoor, renowned for his mirrored works.

“At first I was worried about that,” Prince says. “I don’t want to be thought of as derivative. But…it’s not derivative. It’s my own exploration. We explore similar concepts. The difference is,” he adds cheekily, “I have patents in optics.”

Kapoor’s works have a futuristic quality. Prince’s marry the new with the ancient. Look at the lushly streaked rust on his monumental pieces (he calls it “a gravitational patina”). Look at the intrinsic familiarity of his Euclidean forms, and how far back they go, laden with symbols in art, writing and ritual.

G2V takes its title from the astronomical nomenclature for the sun. The circle, the traditional symbol of the sun, breaks. At the same time, light erupts from within it.

“I’m fascinated by archaeology,” Prince says. “These are both archaeological fragments and futuristic. It’s like a compression of time. And the simpler the form…the more ageless.”

He returns in his studio to Alembic Cube, the eight-foot work-in-progress, named for a vessel used for distilling.

“This is almost an artifact of Richard Serra’s cube,” Prince says. “It’s like we found it, and dug it up, and this is what’s left.”

Rusty planes, a chasm of rippling light. Spirits released.

Cate McQuaid is a critic for the Boston Globe.

Jonathan Prince Studio

1100 Clayton Mill River Road

Southfield, MA

jonathanprince.com

West Branch Gallery & Sculpture Park

Tari Swenson and Chris Curtis

17 Towne Farm Lane

Stowe, VT

westbranchgallery.com

Cynthia Reeves Gallery

28 Main Street

Walpole, NH

cynthia-reeves.com