Thinking Outside the White Cube

Sumin Son, Full Bloom 3, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 32 x 32″. Courtesy of Gallery BOM.

NEW HAMPSHIRE / VERMONT

Arlene Distler

“We always try to keep our eye on the prize,” says Petria Mitchell of Mitchell • Giddings Fine Arts (MGFA)—a beautifully lit and spacious gallery in Brattleboro. For Vermont galleries, that prize is not what one may think—it is not about an expansive bottom line or hobnobbing with the big names in the art world. It is, it turns out, pretty much without exception, about supporting art and artists and about community. The idealism and values that Vermont has come to be known for extends to the gallery scene.

In fact, many gallery owners and managers see their galleries as performing a public service. A reading program has been going on for ten years at BigTown Gallery in Rochester. Edgewater Gallery on the Green and Edgewater Gallery at the Falls, both located in Middlebury, regularly present workshops and demonstrations. Burlington City Arts, a nonprofit which runs BCA and Metro galleries, has an art leasing program for public spaces and institutions such as libraries and hospitals, for which they charge a modest fee. At Towle Hill Studio—a gallery in a little house, in a meadow, off a dirt road in Corinth—they have even taken money out of the equation altogether with no fees or commissions.

Anni Mackay, owner and manager of BigTown Gallery, notes that a passion for what they do is what allows gallery owners to “weather the rough times.” And rough times there have been. Pam Tarbell, owner-manager of Millbrook Gallery in nearby Concord, NH, is probably not speaking only for her establishment when she says, “Collectors are not buying as they once were.” Nevertheless, gallery owners seem to be feeling pretty upbeat. Witness the expanding gallery scene. Tiny Towle Hill has gone from six to twelve weekends this summer; BigTown, Edgewater and Burlington City Arts have all, in recent years, expanded to two locations. Mitchell of MGFA, which is considering expansion, tried to explain her optimism: “People are craving experiences. We and other galleries offer an enhanced art experience. Some people come in to just be in the space, surrounded by art. In these times, it offers connection and solace.”

There is no end to the inventive ways galleries—the big, the small, the for-profits and the nonprofits—are finding to keep doing what they are committed to doing—bringing quality art to Vermont and New Hampshire.

How they arrive there varies, and how they support themselves does, too. Three of the six galleries Art New England spoke to are nonprofits. But whether part of a nonprofit or not, many galleries have programs that bring people into their space and make them more “user friendly.”

Robert Ferris, Inner Heat, wood with gold and silver leaf, 84″ tall, with Towle Hill Studio in background. Photo: Thornton Hayslett.

Location matters, too. Edgewater on the Green manager Theresa Harris attests to the good fortune of being in Middlebury with Middlebury College’s art-hungry and sophisticated population of faculty and parents of students. MGFA’s Jim Giddings spoke of the importance of galleries that have been around much longer than they have as building toward a “threshold” that is making Brattleboro an arts destination. Mackay says she owes much to having the University of Vermont, Middlebury College and Dartmouth as resources. And, Burlington City Arts is located adjacent to Vermont’s main college community, with access to the largest population center in the state, and a strong arts culture.

This emphasis on location extends to New Hampshire as well. Tarbell’s bucolic Millbrook Gallery is located in Concord, not too far from the Currier Museum in Manchester. The Thorne-Sagendorph Gallery (a museum of primarily 20th- and 21st-century artists where work is sometimes for sale), is located on the Keene State campus, and a trip to the gallery is part of the freshman curriculum. Piscataqua Fine Art, is in scenic Portsmouth and benefits from the summer tourism for sales and filling their workshops, according to gallery manager Vivian Gale. The Hood Museum at Dartmouth has a satellite program that “dovetails” with exhibits at BigTown Gallery, says Mackay.

The CYNTHIA-REEVES gallery is another story. She has one gallery at MASS MoCA and another in the upscale town of Walpole, NH, with its fabulous Burdick’s chocolatier and restaurant. However, it could really be located anywhere. Many galleries in Vermont and New Hampshire put a premium on artists’ local connection, even if “local” means anywhere in the state. But CYNTHIA-REEVES has a far reach. Staff members are “constantly doing research” according to Sarah Mintz, gallery manager. They go into New York City every week or two to see clients and attend art fairs from Miami to London seeking artists who are right for their clientele. Their consultancy to corporations, municipalities, collectors and interior designers gives them a “diverse business platform,” says Mintz. “We have,” she adds, artists “from every continent.”

Murray Dewart, Sun Pavilion, powder-coated aluminum. Courtesy of Millbrook Gallery.

Choosing what to show differs, of course, from gallery to gallery. Consistently though, it’s about what speaks to the gallery owner. Mackay says that for the first ten years she showed only work she personally loved. That happened to be largely mid-century modernists whom she calls the forerunners and influencers of artists of today. However, knowing one’s market is essential for good financial health, Mackay acknowledges and cautions that it’s not only about passion. “You also have to be savvy.”

Owners and managers of BigTown, Edgewater, BCA and MGFA all said what they show needs to speak to them personally, yet they also emphasized the importance of maintaining cohesiveness and balance in their offerings. Harris at Edgewater spoke of the gallery’s interest in young, innovative artists while also offering more traditional plein air, landscape and still-life paintings. Burlington City Arts started the Metro Gallery to have a space that would be a better fit for less seasoned artists, as well as making it easier for Vermont artists to show and sell their work.

It seems Vermont and New Hampshire gallerists are a dedicated and special breed of entrepreneur for whom their galleries are a way of life and a mission as much as a business.

Patricia Capell Wolfinger and Cathy Krawaw, Snake, Winsted, CT, from Torrington Yarn Bomb. Photo: Mark Croce. Courtesy of Five Points Gallery.

CONNECTICUT / RHODE ISLAND

Alexander Castro

On June 11, 2016, Five Points Gallery, a nonprofit arts space in downtown Torrington, CT, spearheaded a community effort to “yarn bomb” 200 local sites. With 500 participants—from artists to Girl Scouts to church groups and senior citizens—Torrington’s street lamps, mailboxes, bike racks, fences, benches and other downtown fixtures were covered in splashes of knit graffiti. The sky even opened up at one point, remembers Judith McElhone, the founding executive director of Five Points, yet, “People were putting up their yarn, singing in the rain.”

“I confess I had no idea what a yarn bombing was. I called my daughter and she straightened me out real quick,” says McElhone, who has lived in Torrington all her life and has witnessed its transformation from a blue-collar manufacturing town to one of the largest “micropolitan” areas in the United States. McElhone herself has been part of that metamorphosis, not only for her role directing the gallery, but also for orchestrating this colorful and temporary takeover of the local landscape.

That’s one (particularly spectacular) way to bring art outside a gallery and into the public sphere. Across Rhode Island and Connecticut, galleries are doing what they can to expand their reach. And they are doing this out of necessity. Local collectors who can afford high price tags can travel anywhere they please to buy world-class art, or they can buy it online. Consequently, local galleries have had to get creative to get people in their doors.

First, galleries are no longer spaces solely designed for selling art, nor is selling and exhibiting confined to the physical space. Galleries have become destinations, community venues and traveling exhibitions. Many attend art fairs. Providence’s GRIN and Cade Tompkins Projects both exhibited this past March at the ultra-cool SPRING/BREAK Art Show in Brooklyn, NY. Others might jumpstart their own fairs, such as Westport hosting the first CT Contemporary Art Fair in June. Others post their inventories online, such as Maple & Main Gallery of Fine Art in Chester, CT, which lists its offerings not only by artist but also by subject matter and medium. Sites like Artsy are another popular option for e-commerce.

Community events draw crowds—not only to sell art, but also to foster a sense of camaraderie among artists, galleries and their surroundings. Bianca Griggs, owner of Souterraine Gallery in West Cornwall, CT, hosted a barbecue at her space and welcomed the entire town. Providence’s Occam Projects holds a critique group where artists can come and receive valuable feedback from their peers. These events are prominent at nonprofits like Five Points, and often blend exhibitions with additional programming such as movie screenings or lectures. Jamestown Arts Center in RI, for instance, offers abstract painting, yoga, tai chi, nature writing, ceramics and printmaking on its roster of upcoming classes.

As more and more is offered at these nonprofit galleries, the standard business model of the commercial gallery has needed to evolve. Consider the Kehler Liddell Gallery in New Haven, CT, which is owned and operated by its member artists. They partnered with a local nonprofit to provide additional programming earlier this year: “Artists lead monthly story hours, family movie nights, artist talks, workshops, demos, portfolio review days and more,” says member artist Liz Antle-O’Donnell.

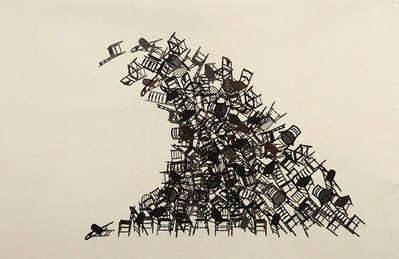

Julia Mandle, Rising Tide, 2012, embroidery on canvas, 23 x 37″.

Nonprofit galleries have a financial advantage, as income from art sales is not their only option. Five Points can apply for grants, fundraise and “do things commercial galleries can’t,” McElhone says, including exhibits that might be enriching but not salable. Local governments and even private investors are eager to support nonprofits, as they can spur development in the surrounding area. What says “hip downtown area” more than artists?

Take Torrington Downtown Partners, a group of investors hoping to revitalize the city’s downtown, who gave Five Points a year of free rent to get started. Strategic partnerships—like one with the University of Hartford, allowing their graduate students to rent inexpensive studio space at Five Points—external support and a gallery to stay financially afloat (and adequately publicized). Still, McElhone notes, “Selling art is important to our bottom line.”

And the selling of that art is perhaps the most daunting task of running a gallery today.

“Don’t do it for the money,” says Renee O’Gara and Dave Gilly Gilstein of Charlestown Gallery in the Rhode Island town of the same name. Affordable rent is a perennial concern, especially when high-quality, thought-stimulating work does not equate to sales. Take Newport, RI, gallery Open Aperture, which showcased contemporary photographers (such as Frances Denny, reviewed in the July/August 2016 issue of Art New England) and shuttered only 18 months after opening.

Newport is a good locale to ponder salability. Flocked to by tourists in the summer (many of them wealthy), it’s a town where profundity does not always sell.

Bobbie Lemmons, creative director of Atelier Newport, describes Newport’s milieu as heavy with “the history of yachting” and the “decadence” of Gilded Age mansions. “That doesn’t mean you have to articulate that history over and over again in your aesthetic,” says Lemmons. She prefers to show a mix of established or emerging contemporary artists alongside fresher takes on the nautical themes typical to Newport dealers.

Still, safe curatorial choices can sustain a gallery. Take Sheldon Fine Art, also in Newport and now in its 34th year of business. While Atelier recently celebrated its first year, Sheldon Fine Art has survived for three decades on paintings of sailboats, waves, swimmers and flowers.

So if you’re going to be bold, it doesn’t hurt to be social or well-connected. Fostering relations with customers, transforming them from one-time into repeat buyers, can be key. O’Gara and Gilstein explain that they have a “loyal group of collectors from Connecticut, New York, Massachusetts and Rhode Island that keeps growing year after year.”

They quip: “Love what you do,” but also, “Have some extra money in your bank account to get through the first couple of years.” Cultivate healthy relationships with your artists; Charlestown Gallery tries to pay within two weeks of a sale.

That might be the essential goal of running a gallery: compensating artists for the wonderment they provide in a world that all-too-often values the utilitarian and unfeeling as the only worthwhile labors.

Says Lemmons: “I take great pride and feel like it’s noble work to feed an artist and keep them from a day job.”

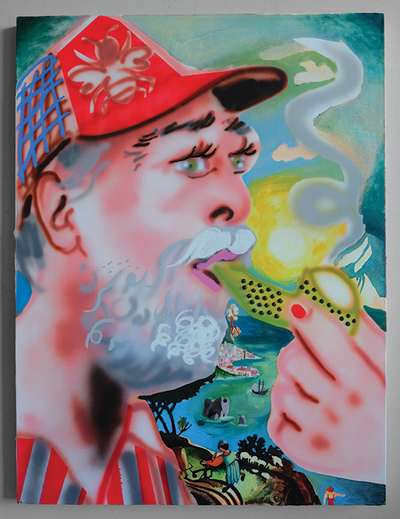

Emilie Stark-Menneg, My Guy’s Smokin’, 2017, acrylic and oil on canvas, 48 x 36″. Courtesy of the artist.

MAINE

Katy Kelleher

Maine has the oldest population in the nation, a fact that is brought up frequently when discussing healthcare, yet equally relevant to businesses that cater to older clientele—and that includes art galleries. “To sustain our business, we have to keep renewing our client base,” says Jack Leonardi of Art Collector Maine. “We can’t sell paintings to the same 500 clients forever. Their houses get full, they get older and eventually those clients downsize.” In order for galleries to survive in the long term, it’s important that they cultivate new buyers of all ages, and many local galleries are finding innovative ways to speak to the coveted millennial demographic.

“You can’t communicate with the younger crowd without having a social media presence,” Leonardi points out, a statement that is echoed time and again from gallerists from Midcoast and southern Maine. Peggy Greenhut, former owner of Greenhut Galleries says that the digital revolution has not only changed the art world, but also the art market. “When I think about the old days, I remember when we would send out a card as an invitation to an opening,” she says. “It would have one, maybe two pictures on it. But now? Now we’ve gotten very good at using Constant Contact. When we invite our clients to an opening, we can send so much information and so many more images.” Cynthia Hyde of Caldbeck Gallery agrees that the proliferation of online images is a positive thing—it leads to more informed buyers, for one—but she also admits that she’s still figuring out how to reach younger buyers. “We just recently hired a young woman to work a few hours a week and do all our Instagram and Facebook posts,” she says. “It’s a task that gives me a headache, but it’s important. The world is becoming even more visually oriented—which many of us were in the first place—and that is very cool to see.”

For some galleries, this has translated directly to sales. Leonardi recalls a recent purchase that transpired after a young woman brought in a screenshot on her phone. “She loved this piece we posted on Instagram by Holly Lombardo, and she wanted to buy it that day,” Leonardi says.

Another experimental tactic that has translated to sales also focuses on bringing fresh faces through the door, but instead of using the power of the Internet, gallerists are using the lure of the experience. Multiple studies have shown that millennials are less interested in purchasing objects as status signifiers than their parents’ generation, instead preferring to collect memories and to make experiential purchases. To capitalize on this trend, galleries have been hosting unconventional art events—sometimes even throwing parties that have nothing to do with the art on the walls at all.

“Many people don’t want to have an event at the cold function room at the Holiday Inn,” says Greenhut. “We have such lovely surroundings, so why not share them?” Greenhut Gallery has hosted mixers for local law students, cocktail parties for nonprofits, and even weddings. “It brings in people who otherwise have only driven by our gallery,” she says. “These events…absolutely they translate to sales.”

Brad Maushart, a painter and gallery owner in Kennebunkport, says he’s always on the lookout for talented acoustic acts or a cappella groups to host at his barn-style f-8 Fine Art Gallery. Similarly, Corey Daniels has held dinners in his York gallery where he invites artists such as Jung Hur (who is also a chef) to plan a menu for a guest list of longtime clients; and Jack Leonardi has partnered with Maine Spirits for liquor tastings.

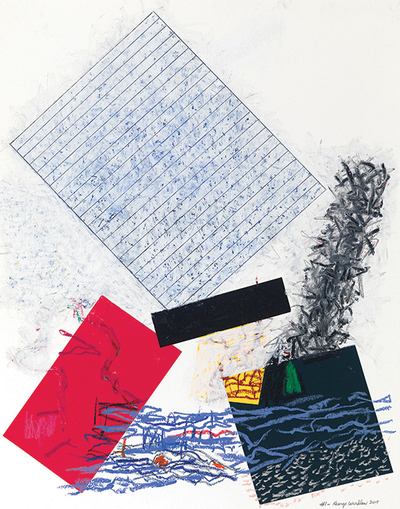

George Wardlaw, Untitled #1, 2015, mixed media on 1975 print, 29 x 22¾”. Courtesy of Yvette Torres Fine Art. Photo: Stephen Petegorsky.

Another way to get works in front of buyers is to bypass the gallery model entirely and bring art into new spaces, like hotels or restaurants. Art Collector Maine has partnered with several hotels over the years to showcase the work of their painters and sculptors in the lobbies and bedrooms of high-end destinations. “Some of our best relationships are with hotels,” Leonardi reveals. “When we first started doing that, people thought it was crazy. But it’s worked. Having art in hotel lobbies has contributed a significant amount to our business in terms of getting people to come to our galleries.” Not only is this excellent publicity for the artist and the hotel, but it also gives out-of-state visitors a chance to experience a slice of the local art scene. This fall, Art Collector Maine plans to take this strategy a step further by offering a residency program at Cliff House, where selected painters can come and paint on the famed shoreline of Cape Neddick. In exchange for their rooms, they will be asked to offer plein air painting workshops to hotel guests. “We’ll pick artists who are comfortable painting outside and have the personality to engage a crowd,” says Leonardi. “Ultimately, the hotel wants art to become a part of their identity, and having artists there regularly as part of the culture of the hotel will help achieve that goal.” It will also allow experience-seeking (and experience-sharing) customers the opportunity to learn from accomplished artists (in an Instagram-worthy setting).

Yet not all gallery owners are enticing young buyers with whiskey tastings and curated newsfeeds; some are simply trying to showcase the kind of art they believe up-and-coming collectors want to purchase. Elizabeth Moss of Elizabeth Moss Galleries has built a reputation over the past decade selling traditional landscapes, particularly plein air painting. While she is continuing to sell this type of work, she also feels the need to “go with my gut on what’s exciting and current.” She cites a July show she held for the up-and-coming painter Emilie Stark-Menneg as being “current in every possible way—the medium, the imagery, the application. They’re so unbelievably exciting, I can’t even tell you.” However, she recognizes that “local audiences don’t tend to respond as well to these kind of shows—but you never know.”

Like Moss, Yvette Torres has committed to selling work that “not everyone will love,” as she puts it. “It’s not about the hype,” she says. “It’s about the work.” She continues, “I show high-quality art and I stick to my guns. If I were constantly thinking about how much money I needed to make each week, which I probably should do, but I don’t, I would move away from my mission.” Her mission, she explains, is to show “real art.” Art that challenges people, that appeals to our humanity, that makes a statement.

Torres’s gallery specializes in mid-century artists, particularly painters from Black Mountain College. While she knows that the art market in Maine has traditionally tended toward representational art—lighthouses, sunsets, lobstermen and other iconic symbols of coastal life—Torres doesn’t let that stop her from showing the bold geometric abstractions of Zola Marcus or the strikingly asymmetrical collages of Nancy Freeman. “Young buyers,” she adds, “love this stuff.”

The Human Canvas. Hosted by the Boston Artist Collective, August 2016. Photo courtesy of Chris Anderson, CDA Media, and Abigail Ogilvy Gallery.

MASSACHUSETTS

Christopher Snow Hopkins

Last fall, Yunmin Zala received an email from a representative of SoWa, a cultural district in Boston’s South End that is home to 38 galleries. “He told me that a space had finally become available, but it was not exactly what I had been looking for,” Zala said. “I had imagined a big gallery on ground level, and this was a small space underground.”

Zala had been thinking about opening her own gallery for almost a decade. Raised in South Korea, she came to the United States to enroll in the Museum Studies program at Tufts University and then interned at the Harvard Art Museums. But, as she discovered, “the museum setting was not quite right for me…I wanted to work with artists who were not already established. My dream was to discover an artist, introduce him, and watch him grow career-wise.”

When she was offered a lease at SoWa, Zala inspected the space several times with her husband and two children and even sat down outside the brick-and-beam complex to monitor the number of people entering and leaving the building. “I really thought about it,” she said. “My youngest one is now two years old, and I kind of wanted to wait one more year. But, I had wanted to do this for a really long time, so I said, ‘Let’s see what happens.’”

I met with Zala in late June at Gallery BOM, where she expounded on her vision for the new space: a platform for emerging artists in the United States and South Korea. The centerpiece of the gallery was Sumin Son’s Full Bloom 3, in which the demure countenance of Audrey Hepburn is overlaid with a fluorescent bouquet. “I told Sumin, right at the beginning, that the Boston art scene is pretty conservative,” Zala said. “If you want to sell pop art, you should probably exhibit in Miami or New York. But, I believe in you, and I want to be able to say that I was next to you and behind you.”

Before the day was over, her gamble had paid off. As I was leaving, I passed a couple from Cincinnati who bought Full Bloom 3 after discovering the gallery by chance.

For many gallery owners in Massachusetts, this is the primary motivation for establishing a business: to discover artists who were previously unknown. Yet, the enthusiasm of a prospective gallery owner is at times a liability, leading to reckless growth or ill-advised business decisions. The vicissitudes of the Massachusetts market seldom match the proclivities of gallery owners, and every year scores of galleries declare bankruptcy.

“People get hurt,” said Andrew Witkin, of Krakow Witkin Gallery, the doyen of the Boston art scene. “If you’re coming from a place of passion, you need to be very cautious on the financial end…You come in, you do your three to seven years, you make your difference and you’re done. The thing that I hate is when somebody does that and they’re in pain, a.k.a. debt, for years to come.”

He added that Krakow Witkin Gallery does not have a secret sauce beyond the desire to “be adventurous yet consistent,” to take risks that complement its brand.

For Barbara Krakow, the gallery’s founder, this has meant enticing blue-chip artists to New England. She was a midwife of mid-century minimalism, organizing an Ellsworth Kelly exhibition in 1966, and five years later, her gallery became the first in the United States. to show Joseph Beuys. Beyond assembling a roster of artists, gallery owners must contend with the more prosaic aspects of running a business: bookkeeping, hiring and firing, granting interviews and negotiating with carriers.

“I think I have ADHD,” said Berta Walker, owner of the eponymous gallery in Provincetown, MA, and a second space in Wellfleet, MA, that opened in 2015. “That makes us lousy students, but it’s great for a . It’s really good to have some Gemini in your blood because you have to be going in five directions at once.”

When we spoke on the phone, the 75-year-old was chugging Muscle Milk as she prepared to dismantle an exhibition, clean the walls and design her next show through an extended process of trial and error. “I listen to the art, and it’s very vociferous,” she said. “I feel what it wants…The gallery will remain open as I’m designing the show, so people may have to look on the floor to find the art.”

Beyond the purlieus of Boston, galleries tend to operate on a seasonal clock: sleepy in winter, manic in summer. Many of the works on view at Greylock Gallery in Williamstown, MA, are infused with a sense of place, meant to evoke the tranquility of country living or the sublime topography of the Berkshires. “People come to Williamstown year after year, season after season,” said Rachele Dario, who set up the gallery in June 2016. “They walk down Main Street, and they look in the galleries. Whether or not they buy something, it’s part of the ritual of being here in town. It’s kind of like visiting old friends.”

Nonetheless, Dario has considered innovative extracurriculars—such as yoga in the gallery—to draw younger clients. “For a long period of time, the biggest collectors were baby boomers, but they’re no longer collecting…If you think of somebody in their 50s or older, their home is full of art already.”

Back in Boston, another gallerist has proposed a new vision of what a gallery can be. In the first year after it was established in October 2015, the Abigail Ogilvy Gallery hosted more than 40 events, with four taking place in one week alone. The aim of perpetual programming—from whiskey tastings to flower-arranging classes—is to boost the visibility of the gallery at a time when a large segment of the market has migrated online.

“The landscape is changing, but we’re not sure what that means yet,” said Ogilvy, wielding a paint-roller in one hand and a smartphone in the other. “But, I still believe that buying art is different from buying a couch or desk—you have to see it in person.”

Alexander Castro is a writer based in the Providence/Boston area.

Arlene Distler is a freelance writer, poet and artist based in Brattleboro, VT.

Christopher Snow Hopkins is an independent writer and critic living in Boston.

Katy Kelleher is the author of the book Handcrafted Maine. She lives in Buxton, ME where she works as a freelance writer, editor and teacher.