To Pop Up… or Not?

Steve Locke, Untitled (Gentrification), 2017, metal with enamel paint, 24 x 48″ with base. Installation image, Immigrancy, Samsøñ, Boston, MA. Courtesy of Samsøñ.

Like the old saying about Mohammed and the mountain… if you can’t get people to the art, bring the art to the people. Whether shuttering a brick-and-mortar space or adding pop-up events to regular offerings, art galleries across New England are exploring the pop-up as a way to cultivate their audiences. There is no single impetus for going nomadic. Galleries are taking into account communities’ tastes, willingness to be challenged by edgier content or art-viewing contexts, and commitment to supporting local art efforts—along with economic concerns.

Samsøñ Projects’ Camilø Álvårez opened Samsøñ in Boston’s South End when galleries there were few and far between. Over the years, his gallery helped generate a cultural renaissance in the area as more galleries set up shop. When Álvårez first moved in, he says, “there were about three or four galleries.” Now there are upwards of 30. The SoWa (south of Washington) Art & Design District, as it’s now known, helped drive economic growth beyond cultural vibrancy. But this didn’t come without a cost.

The phenomenon of gentrification is as established in SoWa as it is in Manhattan’s SoHo. Well-intentioned community leaders and more economically driven developers bring in artists and galleries at low rent prices, which makes a neighborhood more desirable for restaurants, shops and an ever-expanding commercial base. Eventually rents rise, and lower-income tenants—residential and non—are forced to flee.

Álvårez chose to close his doors and go nomadic, not necessarily because the rent had gone up, although that was part of it. He left, he says, because of a series of events that made him feel increasingly less welcome. “As a man of color,” he says, “I’m like a unicorn in the art world.” As Boston’s South End became more racially and economically homogenized, he could no longer reach a diverse range of visitors like those who once wandered in off the street. “It’s just something I couldn’t groove with anymore,” he says.

Further north in Manchester, NH, this is exactly what Kelley Stelling Contemporary’s Karina Kelley and Bill Stelling hope to prevent. Prior to opening the gallery, Stelling helped mount ArtFront NH, a pop-up art and performance event that brought in more than 500 people to downtown Manchester—evidence of a hunger for more cultural events. Although the gallery just opened last year, doing pop-up shows and collaborating with all manner of organizations—from dance troupes to law firms—is part of an effort to test the waters across the socioeconomic spectrum, while building audiences and keeping them surprised and engaged. “We want to keep it a little bit raw, a little bit unexpected,” says Kelley.

Although he made the difficult decision to shutter his gallery, Samsøñ Project’s Álvårez remains optimistic, taking an innovative approach to doing what he does best. “I am basically still selling art; it’s something I want to continue for the rest of my life,” he says. “The way I can support artists is by selling their work and building exhibitions, [although] the exhibitions I do now are itinerant, nomadic.” Álvårez has plans to guest-curate shows and will continue to take his artists to art fairs. He also plans to display art outdoors at his farm in Marshfield, MA. And as a unique twist on the pop-up format, he envisions mounting exhibitions in shipping containers. Rather than sending them where edgier forms are expected—New York, London—he sees them landing in places like Newburgh, NY, or Tulsa, OK, reaching “audiences that aren’t necessarily accustomed to cutting-edge contemporary art.”

This, of course, reflects another prevalent theme for galleries reconsidering their place in the art world. While there’s a short learning curve when it comes to appreciating the finely wrought but ubiquitous New England landscape or seascape, there’s a greater urgency—particularly in today’s divisive political climate—to build awareness and enrich understanding of timely issues through contemporary art. As Álvårez says, “Some of the biggest tragic moments in the U.S. right now are Puerto Rico and those immigrant children. I also want to expose some of the shenanigans going on and mix that in with art and art programming.”

Jana Halwick, director of the newly reopened Carver Hill Gallery in Camden, ME (formerly in Rockland, ME) has shown the work of local, regional and international contemporary artists for more than a decade. With a thriving tourist industry along Maine’s coastline, traditional galleries have done well over the years—and other commercial entities have joined them. “For people in this community who want some diversity of business, we’re kind of losing that a little bit,” Halwick says. In addition, “Keeping a space year-round that’s closed six months I don’t think does any favors for a town.” Going nomadic gave her the opportunity to address both issues by offering exhibitions in edgier locations while cutting back on overhead during the slower months. Her latest pop-up was held across the street from the Center for Contemporary Art in Rockland, which made for great synergy. “But it can be tricky because timing is everything,” she says. “If there’s another event happening nearby, it can either help you get more people or it can cannibalize your audience.”

After trying two pop-up events, despite their success, Halwick became circumspect: “I think it can work, but it takes an enormous amount of energy, resources and fortitude. I figured if I could host five pop-ups in a year, I could afford a permanent space.” So she decided to reopen her doors—this time further up the coast in Camden, which has fewer contemporary art offerings, and therefore, a need for edgier fare. She plans to continue to do pop-ups, but they won’t replace a permanent storefront. “The bottom line is, you just have to try different things…throw different things at the wall and see what sticks.”

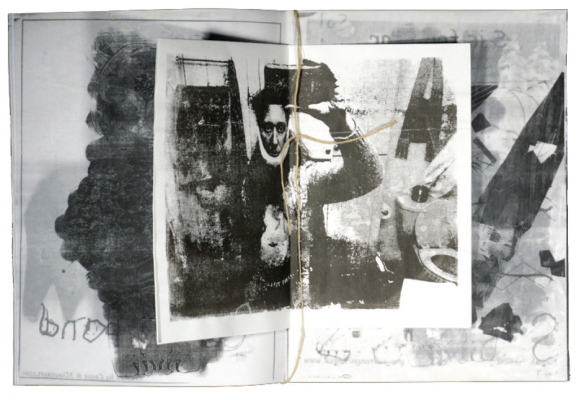

A spread from an artist book by Esther S. White, 10 Things I Did Not Do, made for the 10X10: 2018 Artists’ Book/Zine Swap box set, curated and organized by Trevor Powers for Fugitive Arts. Courtesy of the artist.

Esther White and collaborator Trevor Powers, both visual artists, are doing just that: experimenting. Four years ago they started Fugitive Arts, self-described as “a collaborative, transient curatorial project” focused on showing experimental art by emerging artists in Western Massachusetts. The duo came to doing itinerant art events more philosophically. They were both interested in social practice—art that engages audiences through interaction and conversation, ideally fostering change or at least greater awareness of social or political issues. So for them, the itinerant events Fugitive hosts are a labor of love; neither White nor Powers is in it for economic gain, which is something you hear often in the arts. “We came to it both with this idealistic or very optimistic radical thinking that people need to make art, and we want to be a platform for that outside of commercial activities, because I think it really limits the kind of work that gets seen.”

Collaboration is the key. Fugitive Arts often works with Eastworks, Easthampton’s multiuse building, where they’ve held pop-up events like the Reading Room, an exhibition of books curated from White’s and Powers’s private collections and also a copy of the 12X12: 2015 Artists’ Book/Zine Swap. And unlike a traditional installation of artwork, interaction with the books was encouraged—and the overhead was low.

Following a more traditional gallery model, in semi-rural Rochester, VT, Anni Mackay has run her BigTown Gallery for nearly 16 years. While she has built up a solid following and nurtured her artists’ careers by connecting them with collectors and museums, Mackay decided to try a long-term pop-up about an hour away, in Vergennes, VT, so she could be more accessible to her New York and Montreal collectors. But after one year, she says, “I decided that it was an awful lot of effort to do on a longer basis.”

Anni Mackay owner of BigTown Gallery. Photo: Caleb Kenna.

Mackay, like Halwick, realized the value of a stable location—one you can locate on Google maps. “I put in an awful lot of time and energy into building this business,” Mackay says. No matter what your approach, “you have to have a certain kind of standard and long view of what you’re doing.” Add to that a realistic sense of what you can accomplish—in terms of building audiences, generating income or simply fulfilling a dream. “The best thing I can do for myself…is really showcase great work by people that are enormously talented, not necessarily commercially the best horses to bet on; they tell a story that is quite authentic that has something to with what goes on, on the East Coast at least.”

If there’s one theme common to all, it’s the desire to connect audiences to art. Build it and they will come is a limited concept—rather, reach out to collaborators and audiences and build something that lasts by making meaningful connections. As Mackay puts it, “I’m really interested in the integrity of what I do being complemented by other galleries or other cultural centers or other museums or performance centers…trying to make a very dynamic community for people who are making a commitment to the arts right now.”

Incorporating nomadic elements while maintaining some rootedness seems to be where many smaller galleries and artist collectives are headed, particularly as rents rise and audiences’ attention spans shrink. The need for human interaction will never go away, so these types of interactive events—whether in a permanent or a temporary space—are here to stay. In creating these spaces, as Álvårez puts it, you’re creating dialogue. “That’s where the magic happens.

Julianna Thibodeaux is an independent journalist, art critic, writing teacher and editor. She lives north of Boston.