Cindy Rizza + Leah Giberson

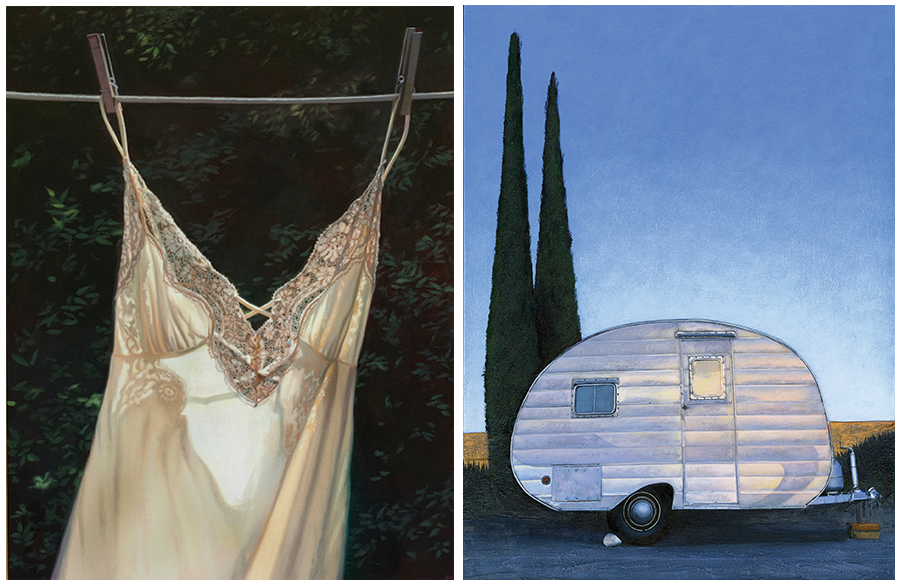

L. to r.: Cindy Rizza, Ghost, 2018, oil on panel, 14 x 18″. Courtesy of the artist. Leah Giberson, Morongo Valley Dusk, 2018, acrylic over photographic print on panel, 12 x18”. Courtesy of the artist.

“What any true painting touches is an absence,” writes John Berger, “an absence of which without the painting, we might be unaware.” This paradox—that art’s presence can conjure absence—permeates the work of Cindy Rizza and Leah Giberson. By focusing on inanimate subjects and omitting background details, both artists capture ephemeral moments, creating poignant meditations on the places we call home.

Giberson grew up in the woods of Warner, NH, so has always been intrigued by the manicured yards and slick surfaces of suburbia. She has transformed this life-long fascination into crisp, alluring artworks that straddle painting, collage, and photography. She finds most of her subject matter outside of New England, though, roaming neighborhoods in Southern California and attending vintage trailer rallies. She then prints and collages her photos onto wooden panels before painting over the entire surface with acrylics, erasing certain details and bringing others to the forefront.

Giberson’s textures and gleaming surfaces are seductive, as are her acid green and cyan palettes. Swimming pools and shrubs invite our touch. The reflective sheen of metal trailers reveal a distorted face here and an anonymous leg there, much like a foggy memory.

While Giberson is intrigued by the exteriors of structures, Rizza’s oil paintings are decidedly interior in nature. In these rich, sultry compositions, possessions such as heirloom quilts, lace slips, and aprons serve as surrogate portraits of their owners, as well as bittersweet observations about the passage of time.

Rizza, who studied figure painting at NHIA, says she finds these still lifes “more human” than actual portraits, which can become “too specific.” Like Giberson, Rizza withholds certain visual clues about time and place, allowing viewers to create their own narratives. There are endless under-stories to be discovered in Rizza’s tattered quilts and sun-dappled slips, as well as in Giberson’s mysterious reflections and half-opened doors.

It would be easy to label these works “nostalgia.” While Rizza and Giberson’s art appeals at that level, there is more to discover in these enigmatic artworks. What is fact? What is fiction? What is home? When does our desire for shelter bring comfort, and when does it become burdensome? How free are we?