Corita Kent and the Language of Pop

Corita Kent, feelin’ groovy, 1967, screenprint. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2008.163. © Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Vivid, nearly overwhelming—visually and intellectually—Corita Kent and the Language of Pop gathers prints and other materials from pivotal sixties American artists Johns, Rauschenberg, Ruscha, and others, including Kent herself. Pop is sometimes accused of over-simplicity, an ironic rejection of its once-vaunted immediacy and accessibility. Warhol’s deadpan approach is denigrated for the same unexamined familiarity it explores. This exhibition challenges such assumptions, foregrounding Pop’s vitality and relevance through Kent’s chiasmic role at the nexus of method and meaning.

Pop art repudiated abstract expressionism’s inwardness, turning instead to contemporary culture to enact what Robert Indiana called “a reenlistment in the world.” Influenced as an artist by these developments and as a nun by the Vatican II call for religious communities to reengage with the modern world, Kent evolved an artistic practice using the materials around her to achieve emotionally and conceptually powerful works.

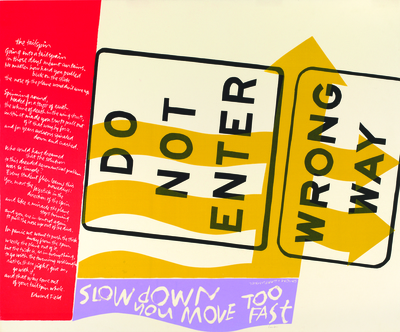

In Kent’s One Way (1967) a traffic sign provides the commanding primary text, but the optics of strong complementary colors, an e.e. cummings text about a joyful fool, and a fatalistic phrase from Simon and Garfunkel, “so I’ll continue to continue,” overthrow its certainty. The song lyric ends somberly—“to pretend / my life will never end”—but cummings’s openness to experience suggests not death but life, recalling Jesus’s proclamation, “I am the way and the truth and the life.” Kent’s appropriates pop culture, transcending its limits, opposing despair with affirmation. Even the overt commentary on political turmoil in works such as Someday Is Now (1964), uniting a Safeway supermarket logo with a fragment of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech, offers both visual fascination and hope.

For secularists, some Kent images seem giddy and overwrought (the exhibit’s signature image, the juiciest tomato of all (1964), included). Yet Kent’s energy and sincerity are always palpable, and her work is never about style, not even Boston’s iconic Rainbow Splash (1971) painted on a Dorchester gas tank. In the context Kent created, Pop communicates social and cultural urgency. Kent’s topics—hunger, civil rights, war—continue to resonate; so, too, does her art.