Toyin Ojih Odutola: The Firmament

Toyin Ojih Odutola is a portrait artist in the classic tradition of Velázquez, Copley or Sargent. Her subjects are opulently attired, their gazes magisterial, the interiors richly decorated. Her details suggest status and rank. She uses a hatching technique that could be found in a Rembrandt or Cézanne. Yet, breaking with tradition and unmistakably contemporary, her subjects are not the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge or the young socialite Madame X, instead they are the UmaEze Amara and the Obafemi—fictional royal families from Nigeria, who are united through the marriage of their two sons.

“I wanted to create a Nigerian royal family, the way the British did—a Yoruba Prince Harry and Lady Diana,” said Ojih Odutola in an interview about her recent show at the Whitney Museum. Yet to call her a “black Jane Eyre,” as she put it, is to miss the point. She is not interested in rewriting history, she’s creating a new narrative—a world where “blackness is unapologetic.”

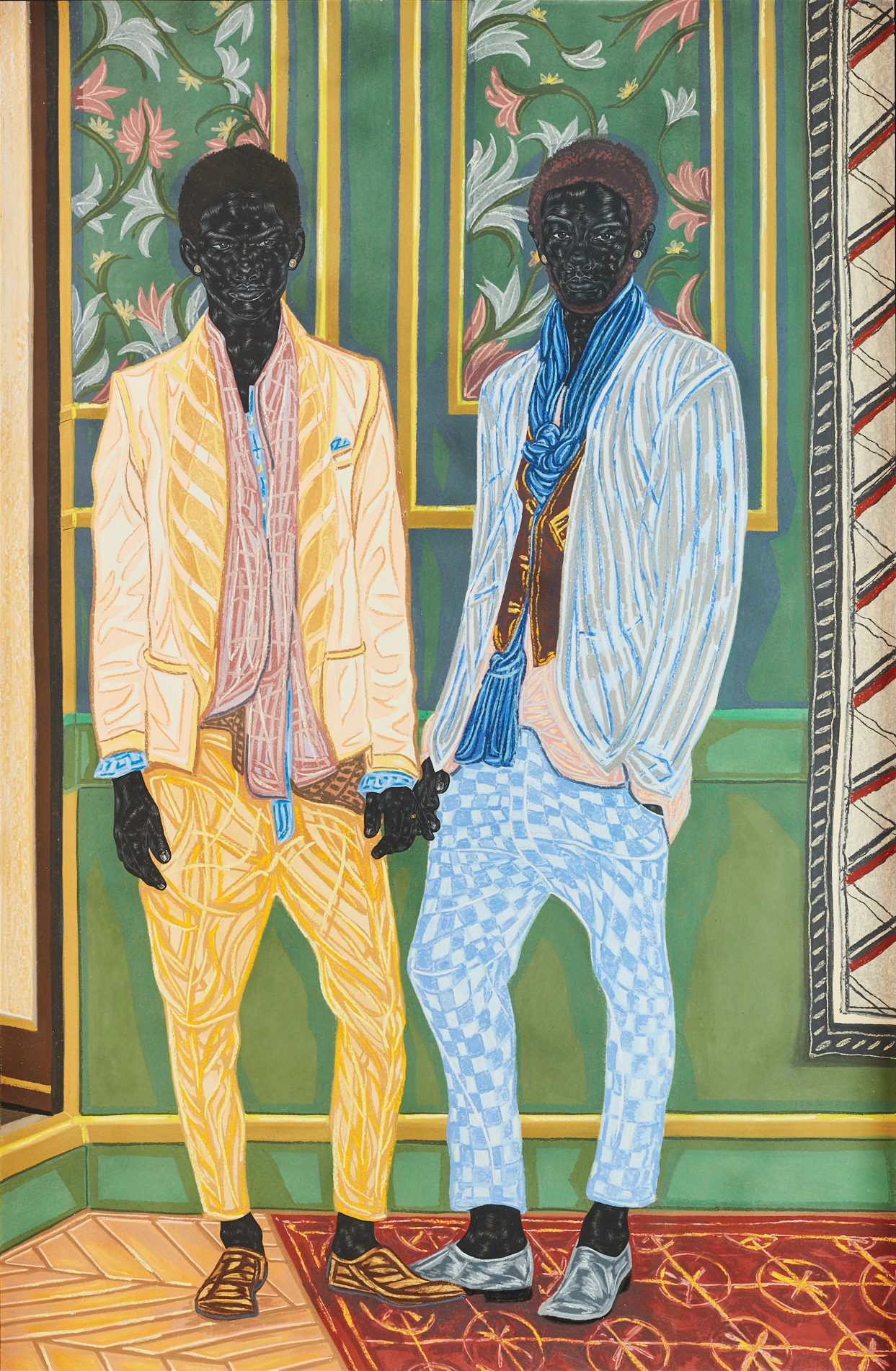

The title of her show, The Firmament, at the Hood Museum of Art refers to the group of people that she has collected in this mythical world. In Ojih Odutola’s narrative, played out in 13 portraits, we see a bearded man looking out across his land in Surveying the Family Seat. In Representatives of State, four exceptionally stylish women pose in front of a large window and a cloudless blue sky. In Newlyweds on Holiday, the two recently married men, who ooze ease and wealth, are smartly dressed with diamond studs, ankle-revealing pants and Oxford shoes. They stand in front of wallpaper that could be by William Morris.

Also breaking from traditional portraiture, Ojih Odutola does not work in oil or acrylic; she uses pastel, pencil, charcoal and pen on paper. And since her portraits are of imaginary people, she combs the web, magazines and Instagram for ideas and inspiration. She’s rigorous and meticulous. She previsions what she wants her faces to look like—the highlights and hatches are planned out in advance. She doesn’t use a brush, she uses her fingers to make her marks and to blend.

Ojih Odutola was born in Nigeria and moved to Huntsville, Alabama, when she was five years old. Like many Africans who move to America, she didn’t know she was black until she got here, according to John Stomberg, director of the Hood Museum of Art. She looks at skin tone and race as an outsider, from an objective perspective. She is known for her rendering of black skin—a hatching of black, brown, white and other colors. “The epidermis packs so much,” she said in a New York Times interview. “Why would you limit it to the flattest blackness possible?”

“Race is a construct and Ojih Odutola deconstructs race with her drawings,” said Stomberg. Her mottled faces remind us, yet again, that there is no such thing as black or brown or white skin. In one of her earlier shows, The Treatment, at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City, she investigated this further by taking images of famous white men and giving them black skin.

In The Firmament, Ojih Odutola’s characters are comfortable being who they are. “There is a strength and nonchalance,” said Stomberg. “It strikes you, like a Kennedy, they are into their blue jean, t-shirt phase of wealth.”

Ojih Odutola earned her BA from the University of Alabama in Huntsville and her MFA from California College of the Arts in San Francisco. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of Art, Baltimore Museum of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Princeton University Art Museum, Spencer Museum of Art, the National Museum of African Art (Smithsonian) and now the Hood with their recent acquisition of Pregnant. She lives and works in New York.

Like Hollywood, the art world is in a moment of self-examination. For centuries, the Western world’s museum walls have hung with portraits by mostly white men. The stories of wealth and power they project has been our visual language. In The Firmament, Ojih Odutola imagines a world where colonization never happened. “If we remove the obstruction, people can enter the story and it’s no longer about pain. It’s real if you can make it,” she said.