Exploring Nan Goldin’s Life and Art

For Nan Goldin, whose intimate images of her life among Boston’s drag queens in the 1970s helped launch the “Boston School” of photography, life, art, and activism have long been inseparable. That continues into the present with Goldin’s fight to hold Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family accountable for the opioid epidemic.

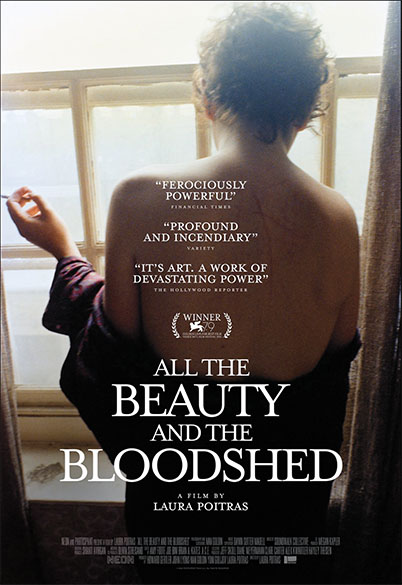

Her crusade is documented by Academy Award-winning director Laura Poitras (2014’s “Citizenfour”) in her new film, “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed.” The film won the Golden Lion at the 2022 Venice Film Festival, rare for a documentary, and was the centerpiece film in the Boston Globe’s annual October GlobeDocs film festival last fall. It’s likely to earn another Oscar nomination for Poitras who deftly weaves multiple narratives in the film.

Part biography, part art history and part thriller, the threads are held together by Goldin, a storyteller who has never shied from depicting her own trauma in her photographs. Without reservation or pretension, Goldin talks about her addiction to Oxycontin, developed when she was prescribed the drug after undergoing surgery while living in Berlin. Her intake rose quickly from three pills daily to 18. Goldin in 2017 founded the advocacy group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) which aimed to stop arts institutions, including museums with Goldin’s photographs in their permanent collections, from accepting Sackler family money and laundering the Sackler name by putting it in places of honor. “They have washed their blood money through the halls of museums and universities around the world,” she says in the film.

Goldin understood that as a world renowned artist, she’d grab attention for the direct actions such as the one that opens the film. Goldin and dozens of P.A.I.N. activists in 2018 filled The Sackler Wing of The Metropolitan Museum chanting “Sacklers lie, people die.” They dropped to the ground for a die-in, recalling similar protests by ACT UP activists during the AIDS epidemic. In another action, P.A.I.N. members released hundreds of prescription slips that fluttered down from the top of the Guggenheim Museum in a compelling visual.

Poitras traces Goldin’s early life as the child of Jewish parents in suburban Boston in the 1950s. Her beloved older sister Barbara committed

suicide in 1965 at the age of 18 after many years in and out of psychiatric hospitals. Goldin, who was 11 at the time, later discovered that fears of homosexuality played a role in her sister’s institutionalization.

The trauma of Barbara’s tragic end pushed young Nancy to literally run away at 14 from suburban conformity and sexual repression. After living in several foster homes, she enrolled in the alternative Satya Community School in Lincoln, MA. where she found kinship with fellow photographer David Armstrong. “I brought him out and he named me Nan, so we liberated each other,” she says in the film.

Goldin later found her tribe in Boston. Between 1972 and 1974, she lived with a group of drag queens who frequented the bar The Other Side. The black-and-white photographs shot at the club provide a rich historical tapestry in the film and show Goldin’s developing yet distinctive, informal yet bracingly, intimate style. After graduating from Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 1978, Goldin moved to New York City’s Bowery, finding a family, albeit a dysfunctional one, among the outsiders, artists, junkies, hookers and drag queens as she continued to document her life among them. The film includes generous samplings of Goldin’s early, influential slide shows set to music such as 1979’s “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” which she screened at New York’s punk rock clubs.

Among the many highlights of “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is the recounting of Goldin’s role as artist and activist during the AIDS era. She included her friend David Wojnarowicz and other artists dealing with the impact of AIDS in the seminal 1989 exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing that Goldin curated at Artists Space in New York. Wojnarowicz’s scathing indictment of the government and powerful institutions for their negligence as AIDS ravaged the gay community drew the ire of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) which withdrew its $10,000 exhibition grant and ignited a firestorm of protests.

The documentary connects activists’ efforts to call out the lies and silence around AIDS to Goldin’s present war against the stigmatization of opioid addiction and her mission to expose the Sacklers’ deliberate deceptions. By the end of the film, Goldin’s life and art come full circle. There is a poignant coda about her parents and her sister Barbara whose eloquent, heartbreaking letters provide the film with its haunting title. Barbara’s short life still looms large for Nan Goldin, influencing the trauma in her art as well as her position as an outsider from where she continues to challenge institutional indifference and abuses of power.