Imprinted: Illustrating Race

The Norman Rockwell Museum • Stockbridge, MA • nrm.org • Through October 30, 2022

In the last room of Imprinted: Illustrating Race, an exhibition at the Norman Rockwell Museum (NRM), artist Hollis King who, in addition to original pieces, contributed artwork from his personal collection (he’s also the showcase’s co-lead on art direction and design), explained in his sweet, serene tone that his Paintings of African Americans with Inspirational Quotes (2021) were directly inspired by a Life article published in the mid-to-late 1940s.

“[The article] mentioned the brown paper bag test. So, I read the article and I don’t think I ever consciously thought of the test,” he said at NRM, the day before Imprinted was set to open in the verdant pocket that is Stockbridge in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts. “So in reading it, I discovered what it was.”

In short, during the first half of the 20th century, the brown paper bag test was when a classic paper bag was placed against a black person’s skin tone. If their skin color was deemed darker than the bag, they were highly subjected to discrimination.

“I felt horrible about it. That someone would do that to another human. Plus, it was also intraracial. So after a few days of sitting with it, I discovered you could go to Dollar Tree and get 45 bags for $1. So I said, Dollar Tree, you’ll be my canvas!”

After pondering how to turn such a colorist, discriminatory practice for past generations of Black people into a positive, uplifting beacon for the community, today, 100 bags later, six of them are presented in a glass case at the museum. They feature Black characters drawn in quietude with King’s sayings, as well as those from from philosophers and writers, such as “When I DIE, I want to come back as BLACK.” And, “WOMEN HOLD UP MORE THAN HALF THE SKY.”

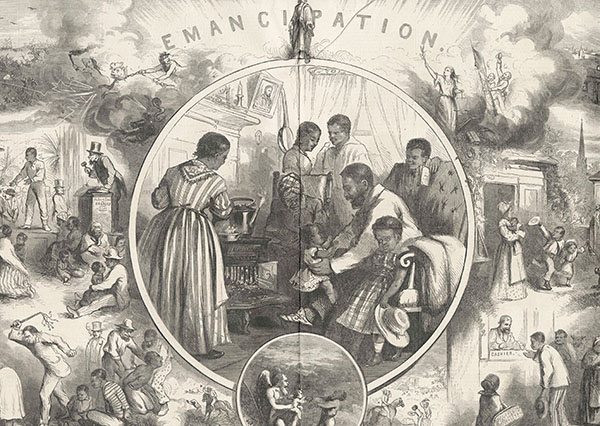

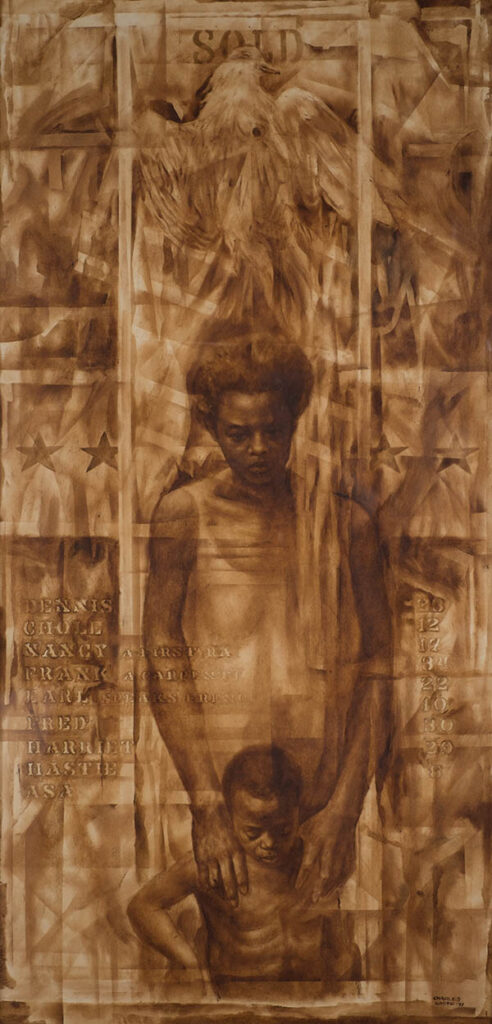

Unknowingly, King’s Paintings embody Imprinted’s purpose and evolution. It’s fitting they’re in the last room because by then, visitors will have experienced the impact of how published and circulated illustrations and cartoons of Black people throughout three centuries have shaped and affected conversations and understanding of race, culture, and—for Black, Native American, and communities of color—respectability, as tropes and stereotypes are deeply explored.

Its four rooms are an impressive, impassioned visual journey that feature illustrations on items as varied as kitchenware, trading cards, food packaging, but also in ads from newspapers, covers of magazines and literary journals, and of course, paintings and sketches.

The first—and each has sub-categories within—is particularly difficult as it contains images that are the most recognizable when it comes to the defamation of Black and brown people. It is a painful reminder of the pervasiveness of racist imagery and hurtful caricatures.

“The more stereotypically racist pieces, honestly didn’t surprise me because I’ve seen a lot,” co-curator Robyn Phillips-Pendelton admits. “There’s way more [than just what’s in here]. And for it to be transported into 2022, the mindset that it was created in, is the mindset of the saturation of the society of the time.”

“[Back then, there was] no television, no radio,” Phillips-Pendelton explains. “You were at the mercy of a society of [in asking] who had the power to create the images. You were not in ‘power’ other than to be treated that way. Who’s in power and who’s not? Who has the power to change it and who doesn’t?”

As she stood in-between the second and third rooms, and Aretha Franklin’s “Think” filled the exhibition, after a beat, Phillips-Pendelton adds, “I felt empowerment as co-curator.”

The oldest piece present is from 1590. Other extremely rare works such as issues of the NAACP’s The Crisis from the 1910s and ’20s and prints from The Picture Poetry Book can be viewed in the second room onward.

“[That] one is super rare,” Phillips-Pendelton informs, referencing the latter that was authored by Gertrude P. McBrown and illustrated by Lois Mailoi Jones. “There’s only one limited print.”

It’s in the second room that visitors will begin to feel the agency of a nation of Black people become greater, more determined and unrelenting in correcting the narrative of the pre-and-post Reconstruction era(s) and showing up for real representation.

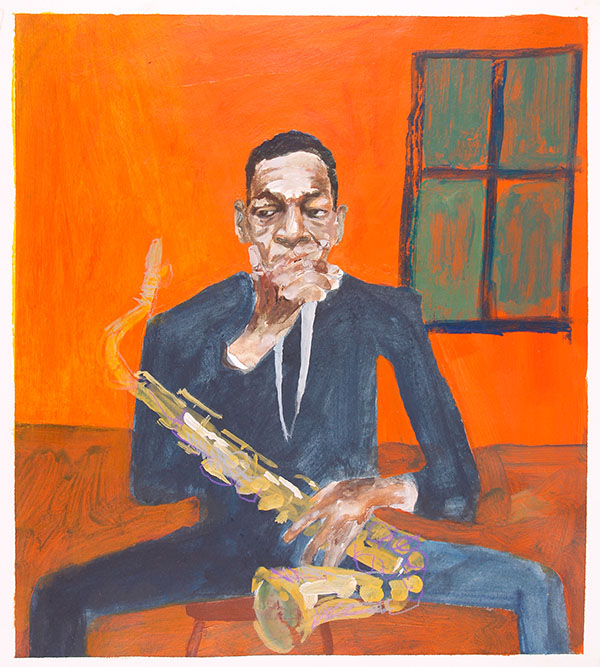

Alongside the rise of the Black voice, aka “The Black Press,” in journals such as The Crisis, the second room is heavy on the influence of the Harlem Renaissance. Including the original publication of a nightclub map of the neighborhood, paintings by Jacob Lawrence, and Harlem native Faith Ringgold’s painted snapshot of a jazz performance in Somebody Stole My Heart (2007).

In the third room—where you’ll see art from the Black Power movement and Norman Rockwell’s foray into civil rights coverage, such as his sketch and painting of Murder in Mississippi (1965)—a rare Patty-Jo doll stands on a table, amidst beauty artifacts of bleaching creams and pressing oils to straighten hair. These products are proof that the pressure to assimilate still existed for Black people amongst the social reckoning of the 1950s and ’60s. (It’s a subtle nod to what former Crisis editor W.E.B. Du Bois termed “double consciousness,” in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk).

Producing Imprinted was a labor of love, taking 15 months to gather and complete for a June 2022 opening. Much of the handiwork was done during the height of the pandemic.

And while the show holds a second goal of being a tribute to the visibility of Black illustrators (past and present—many of whom did not get their due, as Imprinted artist Rudy Gutierrez commented), artworks and material by people of other backgrounds—hence most of what’s on view in the first room, Rockwell, and Chris Hopkins’ beautifully detailed artwork of the Tuskegee Airmen—are included for a specific reason.

“All of the artists aren’t Black. Because we wanted to tell all kinds of stories. Who was telling stories about Black people, as it wasn’t just Black illustrators making images [of us],” Phillips-Pendelton says. “So we wanted to highlight those [folks too]. It takes everyone.”

“[In doing that], we hope that we’re giving a sense of the evolution of where we’ve been, where we’re going, and where we are now,” Stephanie Haboush Plunkett, co-curator of Imprinted, adds. “I think the imagery being created by contemporary artists now is full of appreciation for who people of color are and what they’ve contributed. The work being done right now is hopeful.”

Back in the final room with artwork mainly from the 1990s to present-day—spend time with Alexander Bostic’s Lando as a Boy (2010), an Afro futuristic illustration that sparked some controversy for showing Lando controlling a Jedi lightsaber—King wistfully imagines what Imprinted will do for all that visit. “This is a courageous show for this museum,” he says. “I just wish when I was a kid, we had shows or a book like this so I could know that I could do that too. This is a good place to be.

I also think that this many illustrators doing this work is inspiring. Not only to people who are coming in, but also fellow illustrators in knowing that you are part of a cadre of people telling these stories.”

—C. Shardae Jobson