MAN RISING

The journey of an artist’s pièce de résistance and the patron who made it happen

“A modern-day Picasso! Or a Brancusi or Umberto Boccioni!” exclaimed the patron, rallying support for his beloved artist. He looked straight at us and further declared, “He’s simply the most marvelously talented sculptor one’s ever seen.” The patron is an 85-year-old rheumatologist, small in stature and big in personality. Sprite, bright-eyed, donning a large medical Rod of Asclepius medallion on a thick silver chain around his neck; he is high-spirited when he speaks about everything from human anatomy and unmet medical needs to geopolitical issues but especially, about art. He speaks as expansively about Guernica as he does about appendectomies.

Dr. Kenneth Lippman was a surgeon with the U.S. Army during Vietnam stationed in Tokyo (“They called me Dr. Zipman because I was sewing up soldiers’ arms and legs”) and has been a physician in private practice in Westport, Connecticut, since 1973. He declares himself a humanist and it’s noticeable how completely enthralled he is with everything human—how to heal our wounds, treat our maladies and engage our intellectual faculties. And he has a deep-seated passion for art and, as it turns out, artists.

I first met Dr. Lippman while I was writing the biography of an heiress and art patron of the Midcentury—a complicated character who not only helped start the career of the likes of Noguchi, Bemelmens, Balanchine and Tchelitchev, but was closeted and deeply afraid of being “found out” despite her insatiable desire to help artists succeed. Over the course of my research there was one person in her life I had resisted contacting. Her doctor—Kenneth Lippman. I thought, what could he tell me given patient-privacy laws?

On a whim, I called the doctor’s office. Maybe there was in fact something he could share that would add to my research. We agreed to meet. He handed me his business card and I took a passing glance at it yet then noticed the extensive resume on the backside—University of Paris, Tufts, Cornell, NYU Medical Center, Bellevue Hospital, New York Presbyterian Hospital, U.S. Army, and an long list of awards including his service in Vietnam. We planned to spend a Saturday afternoon at a sculpture garden to talk about my book. Trekking around the property in bright sunshine, enjoying the warm late summer weather, the doctor insisted we look for one particular artist he’d recently discovered. He was determined that we “absolutely must see this German sculptor’s work which is simply extraordinary; believe me, you’ve never seen anything like it!” We soon found a small plaque with the artist’s name on it—Matthias Alfen—yet it didn’t match the piece that was installed; that was odd. Oh well, I thought, we’d eventually see his work somewhere.

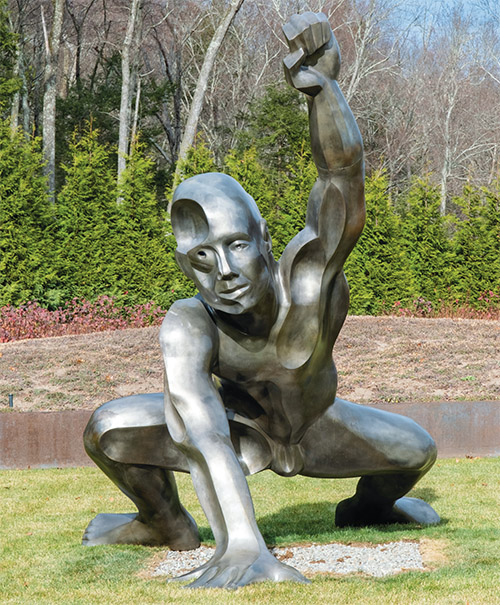

Fast forward five months and I found myself in the same sculpture garden awaiting the arrival of Matthias Alfen’s bronze creation—his pièce de résistance. A group of us—photographers, movers, the collector and the artist—were getting ready to celebrate the arrival of Man Rising, the largest bronze sculpture to be installed in the state of Connecticut. At 12 feet tall and 17 feet deep and weighing several tons, the masterpiece had just spent a week on the road chained onto a flatbed 18-wheeler heading to the Nutmeg State.

Cuban art fabricators with experience in working with Art Basel artists in Miami assembled Alfen’s sculpture over several months; not a simple task given it was originally in sixty separate sections before they prepped it for its inaugural road trip. Their meticulously detailed work resulted in a smooth, virtually seamless piece, polished, with its contours gleaming. The entire process was a labor of love, according to one of the fabricators, who said his crew was “proud” to work on such a monumental artwork.

The sculpture’s new home is at one of the most significant sculpture gardens in Connecticut called InSitu. The landscape structures, rich plantings and large-scale art offer a unique environment to spiritually and emotionally inspire visitors. Eight acres with large-scale vistas of forest and hills are manicured to precision with water features, arbors, stone walls, portals, pools, terraces and of course, the incredible art. The property took more than a dozen years to complete and is a part of the Garden Conservancy’s Preservation Portfolio and privately owned.

Man Rising was originally designed and constructed by Alfen in 2016, yet it took several years for Man Rising’s ultimate acquisition. The journey started with the design of the piece, though the wheels were put in motion (literally and figuratively) by one of Alfen’s patrons, Dr. Lippman. Art patrons possess a conviction and a deep-seated passion for an artist. They typically have the means, financially, socially, or emotionally, to make an introduction, lend a hand, to pave a path for the artist to be seen by others. As Lippman says, “it’s noblesse oblige!” and as Georgia O’Keeffe is quoted, “Whether you succeed or not is irrelevant. Making your unknown known is the important thing.” Art patrons help make the unknown known.

My first meeting with Alfen was at his studio several weeks ahead of Man Rising’s arrival. Once parked on the street of his suburban property, I walked up the long driveway and the first thing I noticed were the Gaudi-esque windows. It was early evening so the illumination from inside made them appear like eyes watching our arrival; and then I heard music. I suspected it was Gustav Mahler—dark, ominous, loud. As I knocked on the door, I noticed what appeared to be half of a large Viking ship repurposed into a sitting area, next to the front entrance. Everything was starting to look and feel creative. Even the studio’s name, etched on the door—Atelier Museum Matthias Alfen (AMMA)—had meaning. “Amma” translates in Sanskrit to mean ‘mother’ and in Arabic, ‘spiritual mother.’

Matthias was literally surrounded by art from the very beginning. Born in 1965 in Aschaffenburg, Germany, he grew up in a household where conversations at the dinner table centered on art of all mediums. His grandfather Klemens Alfen was an accomplished painter and photographer recognized for his landscape work. Matthias’ mother and father were commercial landscape photographers, his godfather, Fritz, bought young Matthias art supplies and purchased several of his early works; and Matthias’ uncle, Fritz Koenig, created the monumental cast bronze sculpture The Sphere which sat between the World Trade Center towers in New York from 1972 until September 11, 2001. Miraculously recovered, albeit damaged, it was reinstalled at the Memorial Site at Ground Zero where it sits today.

Despite the familial influences, Matthias charted his own unique path by sheer grit and as a result his work has been shown in over thirty exhibitions in Germany, Connecticut, New York and France. In his homeland, his work has appeared at the Galerie Noe, Galerie Bremer, and Freie Berliner Kunstausstellung, the Galerie of the City of Soest, Galerie Clasing, and the Neue Kunst Galerie; The Housatonic Museum of Art, (Bridgeport, Connecticut); and Gallery Shchukin, (New York City). His work has also been included in group exhibitions at Artspace at the University of New Haven; the Nardin Gallery, the Garth Clark Gallery, John Elder Gallery, all in New York; the Chesterwood Estate and Museum in Stockbridge, MA; Salon d’Art in Saint-Germain en Laye (France). Additionally, Alfen has received art commissions from the German Federal Government; the City of Soest (Westphalia); Hypo-Vereinsbank, (New York); and Landesbank Baden-Württemberg, (New York). He’s been busy over his forty-plus year career. Yet as with most artists, there is often a struggle to keep commercial momentum going over the long term—to get the work shown, acquired and appreciated.

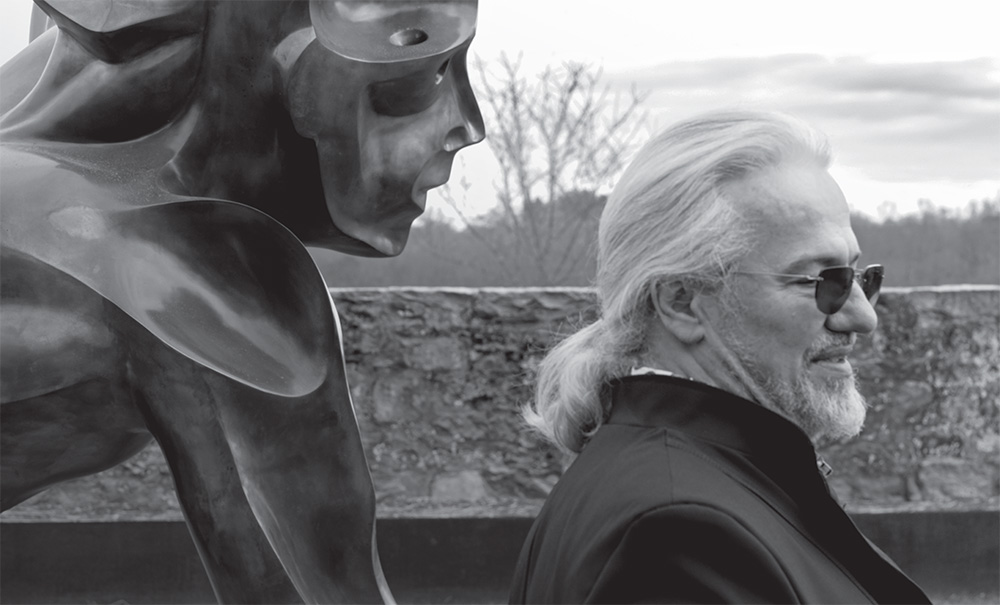

As I walked into AMMA my eyes zeroed in on Alfen sitting on a couch in the middle of the cavernous, brightly lit room. He was surrounded by an impressive array of sculptures, large and small, all contemporary and figurative. Some towered significantly beyond life-size, others perched on pedestals at eye-level. The artist wore a tight-fitting azure leather jacket over a bulky orange hoodie. He’s stocky with a mane of thick, shoulder length hair framing a serious face and piercing eyes (think Jason Momoa). To my surprise I felt uncharacteristically shy. I meet an inordinate number of people every day in my line of work, yet artists often make me a tad starstruck. Luckily my German husband, who accompanied me on this visit, immediately spoke with Alfen in their shared native language providing me a moment to recalibrate.

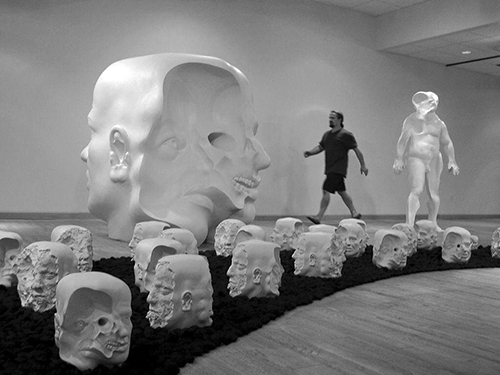

Alfen is a prolific artist, deeply committed to his craft. In the studio, he gently escorted us toward each piece in his collection, stopping to describe the individual piece, highlighting what we were looking at, how he came to design it, the intricacies of what, at first, looks simple only, upon a turn of the head or turn of the sculpture, to unveil a complex figure that creates a viewer to pause. “The dichotomy of my work is a big element that is consistent in most pieces. Since the sculptures transform within themselves from negative imprint to actual physicality the smoothness makes the transition effortless,” he points out. The concavities, the gender fluidity, where there are smooth surfaces and neutral colors to soothe the visual palette before being drawn into features with double meanings and complexities. The duality, the push-pull of emotions. He pointed out that “realism is heightened between the spaces”.

Artists are not typically comfortable with self-promotion, yet Matthias has done a yeoman’s job of grassroots marketing by producing an array of YouTube videos, a detailed and visually interesting website, a Wikipedia page, and an active Instagram following. He’s highly productive and his platform is accessible. He isn’t a showman but confident and compelling in his authenticity about not only his own art, but art in general. He says what he thinks and speaks freely and convincingly about how art heals. One would find it difficult to just take a passing glance of his work. In fact, his large-scale pieces make you look more than just twice. Discovery unfolds the longer one looks. The sculptures are human-like forms, which is obvious. Yet the elements that are most intriguing—the juxtaposition of the convex and concave, the twisted torsos that blossom into gender fluidity—are of course purposeful. They beg questions: Is it a man, a woman, is there anger, ecstasy, sadness? The empty spaces amongst the expected lines of the body make the observer pause in contemplation. Alfen believes in the power of art and human healing—much like his patron Dr. Lippman.

After seeing Alfen’s work several years ago Lippman simply hand wrote a letter to the owner of the sculpture garden, an investment banker and avid art collector, and mailed it. No email, text, or Instagram message. It happened via the United States Postal Service. In the letter, Lippman mentioned his “extraordinary privilege” to tour the owner’s property and how he was left “utterly speechless with ravishment” at the gardens. And then, the patron went in for the close, “I have a dear friend…producing sculptures that are figurative but with striking concavities and convexities” and “he’s a genius.” That letter led the collector to contact Alfen, and the rest, as they say, is (or will be) history.

Viewers will undoubtedly question Man Rising’s meaning. We will discover our own reactions, we’ll query the duality of a man’s head and body cast downward then by taking a few steps to the side, recognize the figure rising up from repose; we’ll notice the raised fist in triumph. There are obvious assumptions—a Phoenix rising, the symbolism of hope, resilience, survival. While we are small in the world, the figure is simply mammoth, as are many of our issues, yet perhaps only in our minds. What we most hope for is that the sculpture brings positivity and recognition of the creative journey—for the artist and for the patron.