Ms. Independent

Museums and galleries have long hired independent curators for a multitude of purposes from hands-on exhibit installer to art advisor. Freelancers have historically been employed to add a fresh perspective and specialized content and wear many hats as critics, consultants, educators, and editorial writers. For Anita Bateman and Nico Wheadon, being an independent curator means adding their own creative influence.

With a Ph.D. in art history and visual culture, Bateman specializes in modern and contemporary African art, the art of the African diaspora with additional expertise in the history of photography and Black feminism. Now living in Providence, RI, Bateman has held positions at the RISD Museum, the Williams College Museum of Art, and the Nasher Museum of Art. She began her career at an institution with university affiliation yet started freelancing in order to work with more artists and expand her interests. According to Bateman, the job now gives her flexibility and allows her to take a more holistic approach to artists.

Like Bateman, Nico Wheadon carries an impressive resume. Among her appointments are inaugural executive director of NXTHVN, inaugural director of public programs and community engagement at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and curatorial director of Rush Arts Gallery. Her manuscript, On Museum Citizenship: A Toolkit for Radical Art Pedagogy, Practice & Participation, is slated for publication in May 2021. As a non-hierarchical person, Wheadon, who is based in New Haven, CT, admits to not fitting into institutional roles without built-in growth opportunities yet acknowledges benefits to working within a museum structure, among them having an established platform, existing resources, and a fixed team.

As freelancers, both women have the flexibility to actualize shows, connect with talent,and become advisors. “My vision for what I want in an exhibition usually gets supported [whereas] there might otherwise be competing factors [in a traditional setting],” said Bateman.

She also admits smaller museums and galleries allow her to work with artists she is loving in the moment and bring lesser-known artists into the fold. Part of the benefit for Wheadon is the agency and autonomy that is built into the life of freelancers. “Within the museum hierarchy, the curator’s voice projects most audibly, often carrying with it the political agenda of the institution. As an independent operating outside of these power dynamics, my commitment is to the artist’s voice first, and to ensuring their message sparks a reciprocal dialogue with the public,” says Wheadon. While the work of in-house staff and freelance functions similarly, Wheadon feels there is more room to negotiate the terms outside the confines of a salaried job.

Bateman is attracted to the independent work because it allows for greater creativity, which she admits sounds strange for a position as creative as curator. It is not uncommon for museums to have their exhibition calendar forecasted for a two-to-five-year period. Newly appointed museum curators inherit the existing schedule which could mean a delay in their influence. Wheadon concurs and favors the immediacy present in smaller organizations and grassroots art institutions. “My priority is adopting practices that respond in real time to what’s happening in culture and society today,” Wheadon said. This allows the independent curator to operate outside of the bureaucracy built into more formal institutions.

Hiring an independent curator allows museums to expand their network of artists and integrate an expert in a particular field. Bateman uses the example of Chaédria LaBouvier and the show “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story” at the Guggenheim in 2019. Through her own academic research, LaBouvier brought a critical lens to the artist’s hostile history with law enforcement. In this case, Bateman says, “curators also specialize in theoretical frameworks that underpin the show like decolonization initiatives.”

An unaffiliated curator can also create a dichotomy within the institution itself. Hiring a freelancer allows for radical exhibits in an otherwise traditional institution which Wheadon asserts burdens the outside curator to ‘shake things up.’ “I’m wary of majority-white institutions that hire independent curators of color to incite a provocation or generate a surface-level optic that the institution is trending progressive,” Wheadon said. Still, these assumptions can be adjusted at conception allowing the freedom to curate a show that aligns with both the museum’s intention and the curator’s values.

While the role of an independent curator may be diverse, the institutions themselves are often not. From hiring practices to largely white exhibits to artist compensation, the public is now holding art organizations accountable for their systematic politics. Coupled with the call of museums to return their looted or stolen artifacts through colonization back to countries of origins, institutions are having a moment of reckoning. The conversation on how to rectify art institutions and their values is creating what Bateman describes as a “paradox of visibility.” There has been a rush to appoint BIPOC leadership, have BIPOC exhibitions, and explain their foreign excavated exhibits. “The majority of white led institutions have erased the experience of BIPOC, queer, and disabled communities,” says Bateman. “It is now incumbent upon them to address the criticism of the wider public.” This has all led to a paradigm shift in the art world. Wheadon’s course of study, a MA in creative and cultural entrepreneurship from Goldsmith’s College University of London, was expressly intended to step out of the white box. “I chose to study creative and cultural entrepreneurship because I wanted to learn vocabularies, refine skills, sharpen tools and build institutions in community with other artists,” Wheadon said.

While these conversations around visibility are important, Bateman wants to be conscious that the language we’re using doesn’t further erase the legacy of the artists who came before. She stresses the need to amplify all BIPOC artists, past and present. She speaks to the retrospective of Lorraine O’Grady at the Brooklyn Museum as an example of an artist being celebrated in life, rather than posthumously. “So many artists of color, especially Black women artists, haven’t lived to see their work, not even celebrated, but engaged by the general public,” Wheadon said. Artists now have an opportunity to be circulated in the community although Wheadon admits we still have a long way to go.

Wheadon and Bateman find their work through word of mouth, call for submissions, and networking in what they both agree is a small art world. The paradox in visibility is something Wheadon experiences in the opportunities being presented to her. Having had to say yes to many projects in the past for the paycheck, this recognition feels new despite being in the industry for decades. “Sadly, the work of education, public programs and community engagement—which is where the crux of my experience lies—is so undervalued,” says Wheadon. The opportunities also speak to COVID layoffs of low paying museum workers (who happen to be people of color) contradicting the museums’ solidarity statements with the Black Lives Matter Movement following the death of George Floyd. We are now left with an art culture forced to reconcile with its past. “Artists of color are more seen than ever, but they are still fighting for that social and economic power within the institution,” says Bateman.

Wheadon worries about the current trend of hiring people of color to leadership positions within institutions. We can look at the LaBouvier example for fallout. LaBouvier maintains she was not properly credited for her work and not invited to a discussion panel about the show. “Chaedria was the first black woman to curate a show at the Guggenheim in its 80-year history of operation, and she wasn’t even permanent staff,” said Bateman. Both women remain concerned with the ‘rapid-fire appointments’ in historical white institutions. “It feels like “progress,’ but the truth is, I don’t trust that the institutions have the infrastructure to support that leader,” Wheadon said. Bateman agrees most museums are lacking when it comes to retaining BIPOC staff members.

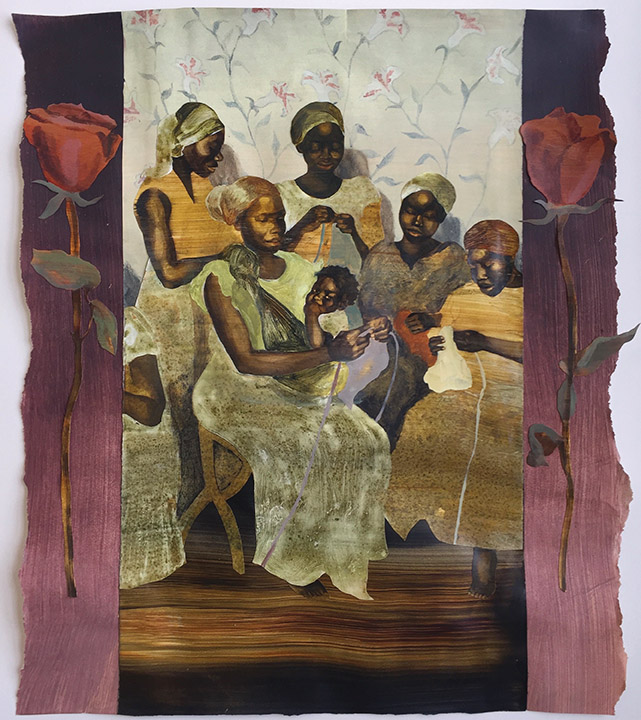

The content that traditionally centered around Black artists might have been two-hour initiatives as opposed to two-month long exhibits. The work is being done both with internal fixed conservators and the aid of hired curators. Progress is measured yet on an upward track. Wheadon contends there is slower work transforming the museums from the inside yet for her, the biggest motivator remains the artist. Look no further for proof of their commitment to talent and community—rather than plugging their own work for this piece, both women preferred elevating the platform of a local artist they admire. Bateman promotes the work of Sophia-Yemisi Adeyemo-Ross, a Providence, R.I., based visual artist while Wheadon upholds the work of Connecticut-based photographer, Ebony B. If progress is a fire, gestures like this are the gasoline.