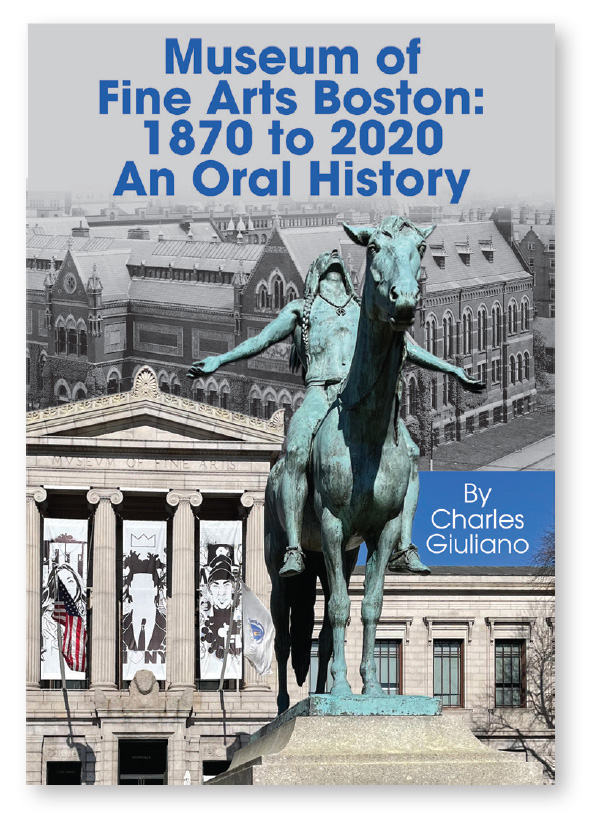

Museum of Fine Arts Boston: 1870 to 2020, An Oral History

Charles Giuliano’s Museum of Fine Arts Boston: 1870 to 2020, An Oral History (Berkshire Fine Arts LLC, 2021) is a groundbreaking contribution to the history of “a world-class, encyclopedic museum” (284). While Giuliano is a champion of the institution that has fascinated him since his first visit with an uncle in 1949, and where he held an internship in 1963, his account is often critical. He staunchly believes in the MFA and hence, wishes to hold it to the highest aesthetic and ethical standards. Eminently readable, Giuliano’s style could be described as journalistic: he weds recollections and historical narrative, recounted in short, punchy paragraphs, with transcriptions of interviews (almost exclusively) conducted by the author.

As much of the book stems from interpersonal interactions, he remarks that its creation “has literally taken a lifetime.” Giuliano merits contextualization as well. A figure in the Boston counterculture, he began as an artist, spent a significant part of his career as an art and music critic for alternative and mainstream publications, and worked as director of exhibitions at New England School of Art & Design/Suffolk University. He draws on this deep Boston knowledge to weave local histories throughout. Giuliano’s literal lens also shapes readers’ sense of history: handsome photographs taken almost exclusively by the author illustrate the book.

The last history of the MFA, by Walter Muir Whitehill, coincided with the centennial in 1970. Other than a chapter surveying the museum’s 150 years, Giuliano picks up where Whitehill leaves off. The 19 chapters generally progress chronologically and by directorial regime; however, they focus on distinct agents—directors, curators, board members—within the museum. His attention to individuals and their impact aligns Giuliano’s volume with more academic writing tracing the increasing prestige of curators in the same period. Nevertheless, in addition to chapters like “The Rathbone Years” or “Barry Gaither, Curator of Afro-American Art,” there are thematic chapters that explore “Centennial Introspection” and “the Museum as a Business.”

Giuliano’s frustration with the MFA’s historical ambivalence toward progressive contemporary art is one of the book’s key themes. He highlights an exceptional exhibition understudied by art historians, Earth, Air, Fire, Water: Elements of Art (1971), curated by Virginia Gunter. Elements included works by an number of major artists (Robert Smithson, Otto Piene, Hans Haacke). Ultimately (29-31), the MFA opted for a more conservative course and named Ken Moffett to be the first curator of modernand contemporary art in 1972; he led the museum to collect “within the narrow confines of Greenbergian formalism” (31).

Furthermore, Giuliano often anticipates pressing contemporary issues and reveals the MFA’s increasing orientation toward inclusivity and social justice. He details the relationship between the museum and the National Center of Afro-American Art. Even as he highlights the positive, Giuliano does not shy away from blemishes, such as the 2019 racist incident (118) to longer running anti-Semitic currents. “Malcolm’s Unionbusting Blues,” a chapter alluding to director Malcolm Rogers, actually consists of an interview with Union representative Gary Lombard describing the successful unionization of the MFA’s guards in 1995 (opposed by Rogers). With this choice of topic, Giuliano underscores the complexity of museums, which are of course not synonymous with their directors or curators. Only in November, 2020, did employees across the MFA vote to join UAW Local 2110.

Giuliano furthermore was ahead of his time with questions to director Jan Fontein regarding the provenance and repatriation of works; his 1976 inquiries recall the questions museums confront today regarding the decolonizion of collections and return of works of art acquired in problematic circumstances. Similarly, he argues for transparency of directorial boards and, in a sense, speaks truth to power in his interview with board member Lewis Cabot, who artfully dodges a question about his CIA links (144).

Museum of Fine Arts Boston celebrates the MFA’s shift away from its elitist “Brahmin” roots towards greater inclusivity, diversity, and relevance. Indeed, the MFA is beginning to catch up with Giuliano’s ideal. Related to this, current director Matthew Teitelbaum emerges as a particularly sympathetic figure. The book pairs a 1993 interview with Teitelbaum with one from 2019. The only element missing from Giuliano’s tome is an index, which hopefully will make it into a revised edition. Regardless, Museum of Fine Arts Boston is required reading for anyone wishing to learn more about the MFA.

- John A. Tyson