Re-thinking, Re-telling, Re-installing

The Rose turns 60 with Frida Kahlo: POSE

The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University has embarked on a journey. Amid social ferment, it is propelled by a “vision for a more inclusive and equitable museum: a nexus for arts, for communities, and for social justice”—as stated in the introductory panel to re: collections, Six Decades at the Rose Art Museum, an expansive and engaging exhibition that marks the museum’s 60th anniversary. In accord with that mission, the un-retrospective proclaims that it “challenges the conventions of art historical narrative by uncovering new connections, charting alternative genealogies, and inviting innovative interpretations of modern and contemporary art.”

That approach is further expressed in the current companion exhibition, Frida Kahlo: POSE, a multifaceted close-up of the artist’s complex identity and creativity.

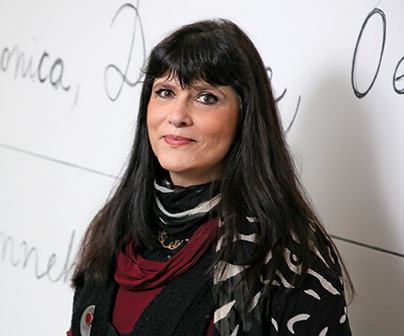

Not about to trot out its warhorses, the curators, Gannit Ankori, Henry and Lois Foster Director and Chief Curator, Dr. Elyan J. Hill, Guest Curator of African and African Diaspora Art, and Caitlin Julia Rubin, Associate Curator and Director of Programs, Brooklyn, New York, have mined the Rose’s world-class collection of contemporary art to display canonical artists alongside emerging and historically underrepresented artists. They’re re-thinking, re-telling, and re-installing.

Across three galleries, disparate works are not grouped by era or genre, but rather are placed in juxtaposition, in dialogue with each other, under the guiding themes of “re: collections,” “re: presentations,” “re: tellings,” “re: citations,” “re: constructions,” and “re: visions.” The must-read wall text is deepened by the occasional “signed’ observations of the curators and by quotes from the artists.

The reimagining of the museum and the presentation of the two current exhibitions is led by Ankori, who is also professor of art history and theory in the departments of Fine Arts and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Brandeis University. She’s served as the museum’s director since January 2021.

“Pursuing an uncharted path, we are transforming the Rose into an antiracist, anticolonial institution,” says Ankori. “We are exploring new inclusive and more equitable ways of being a cutting-edge and inspiring museum that harnesses the power of art and ideas to create social change.”

A Jerusalem native, Ankori joined Brandeis in fall 2010. From 2014 to 2019, she served as the founding head of the Division of Creative Arts. As the museum’s faculty curator, 2013 to 2017, she curated three exhibitions on Israeli and Palestinian art. Before coming to Brandeis, Ankori served as the Henya Sharef Professor of Humanities and Chair of the Art History department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and as a visiting associate professor at Harvard Divinity School and Tufts University School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Ankori’s published writing has explored topics such as gender, nationalism, identity, religion, exile, and hybridity. She is internationally renowned for her groundbreaking scholarship on Frida Kahlo. Ankori and Indigenous Mexican fashion curator Circe Henestrosa co-curated exhibitions on Kahlo, in London, New York, San Francisco, and the Netherlands as well as the current Rose show.

The exhibition starts with three related works. In his abstracted Reclining Nude (1934), Pablo Picasso accentuated the breasts and buttocks of his teenage model, mistress, and mother of his daughter. To the curators, he has painted the object of his male gaze and pleasure.

Two works down from Picasso’s painting, Tahitian Figure (CA. 1894) by Paul Gauguin is a romanticized artifact of his sojourn in a Tahitian “paradise,” where the 43-year-old painter (from colonizing France) took a 14-year-old girl as his bride.

The curators are quick to call out these iconic artists, and thus introduce museumgoers to an approach that employs an expanded, probing perspective that yields, new, sometimes startling, sometimes critical interpretations. Similar narratives and connections are drawn throughout the exhibition for visitors to follow or decipher. Ankori and her compatriots aim to replace the master narrative of Western art history with multi-voice narratives that stimulate new ways of experiencing and understanding both the familiar and the new.

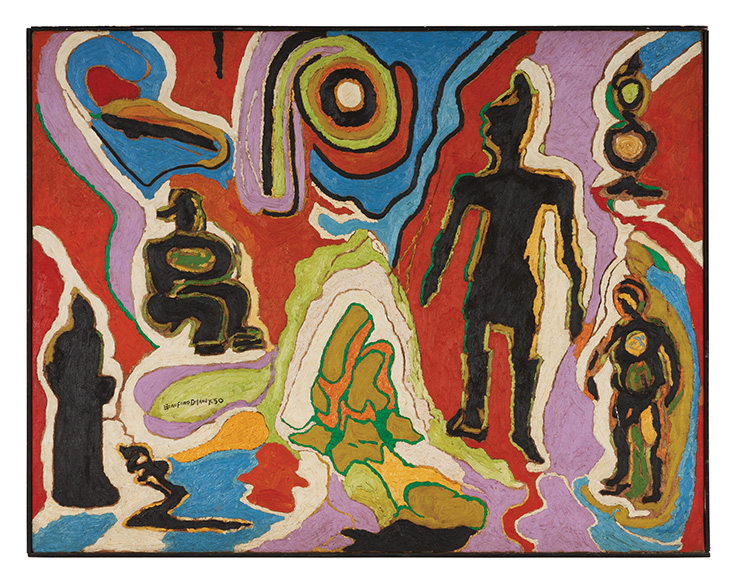

Between the two works, Beauford Delaney’s Abstraction (Greene Street) (1960) depicts four silhouetted figures amid a jazzy landscape, which are not sexualized or fantasized. Instead, Delaney, a Black, openly gay artist active in both the Greenwich Village avant-garde scene and in Harlem’s renaissance, evokes the vibrant community he clearly loved.

The lower Rose gallery, its subdued walls matched by somber images, is the historical center of the exhibition, grounded in traumatic events that happened “in the world outside the gallery,” from the ’60s and beyond.

Under the “re-telling” category, the specific experiences portrayed by photojournalists and visual artists include the struggle for civil rights and racial justice in the United States; the Holocaust; the HIV/AIDS epidemic; colonialist exploitation; gender inequality; and the slave trade. Onlookers are made to witness and contemplate personal and collective histories rife with sorrow, tragedy, and pain.

For example, in William Villalongo’s Veritas (2017), a spectral figure extends a silver tray bearing a color mugshot of the white supremacist Dylann Roof, who murdered nine worshippers in a historic Black congregation in Charleston, SC, in 2015. Recalling the bombing of the Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963, Villalongo states “It is the image of Roof and those like him that is the mirror we need to confront, not an image of the slain.”

And just a few feet away, the Holocaust is invoked in the photograph I Cried When I Saw This Picture, December 15, 1939 (1939) by Weegee (formerly Arthur Fellig), a Jew who in this moment had to put aside his photo- grapher’s objectivity.

At the exhibition’s midway point, its centerpiece: Storm at Sea (2007), Radcliffe Bailey’s sculpture amasses piano keys to evoke a turbulent sea cascading across the floor, with a dark glittering ship at one end, and an assertive African icon at the other. The sculpture calls forth histories of Black individuals kidnapped and forced onto the slave trade’s Middle Passage. When viewing the symbolic work, onlookers bow their heads; it’s a hallowed space.

With three categories—“re: constructions,” “re: visions,” “re: citations”—arrayed in a large, bright space, the third gallery is positively kaleidoscopic. Visitors are advised to respond to what attracts, familiar or not, and trace their own threads.

“Re: constructions” groups artists who, amid “rupture and calamity,” dismantle and mend, fashioning new pathways of expression. Visitors encounter, for example, shredded, colorful canvases reconfigured by Al Loving and Mark Bradford; collages and assemblages by Robert Rauschenberg and Louise Nevelson; Mark Dion’s transformation of refuse into treasure, and Grace Hartigan’s landscape/abstraction, Frederiksted (1958).

“Re: visions” displays the process of world making, where the unleashed imagination creates “bold new universes and selves,” as seen, for example, in Tracy Moffat’s silk screens of otherworldly tales and spaces and Elle Pérez’s eerie yet beautiful portrait photo, Nicole (2018). Evoking the musical sphere in divergent ways, Florine Stettheimer’s Music (ca. 1920) is ethereal and fanciful, while an early Marsden Hartley, Musical Theme (Oriental Symphony) (1912–1913), is dynamic and spiritual. Plus, there’s René Magritte’s L’Atlantide (1927), positing, but of course not resolving.

“Re: citations” presents a cadre of art re-definers, including Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Andy Warhol, who deploy off-center forms, content, and techniques to extends art’s boundaries and societal norms. Chéri Samba in his comics-inspired Les Capotes Utiliseés (1990) delivers an AIDS prevention message to his Democratic Republic of Congo audience.

At the end of the third gallery, in dialogue with the adjoining re: collections, Frida Kahlo: POSE plots compelling narratives that explore the artist’s image and how she realized it. Through a rich array of select paintings, works on paper, ephemera, photographs spanning Kahlo’ entire life, and her own words, the show reveals how Kahlo (1907–1954) melded the workings of photography, fashion, and art, and deliberate identity construction into a multifaceted persona.

Like re: collections, the exhibition is organized by themes: “Posing,” “Composing,” “Exposing,” “Queering,” and “Self-Fashioning.” The exhibition reveals that posing for photographs, not painting, was Kahlo’s first form of self-expression. Later in life, she collaborated with famous photographers, including Imogene Cunningham and Henri Cartier-Bresson, to maintain her well-controlled image. As the result of childhood polio and traumatic injuries sustained as a teenager, Kahlo lived a life of pain, dependent on numerous corsets, braces, and wheelchairs throughout her life. Considered a pioneer in fashioning the disabled body, Kahlo adopted the traditional Tehuana dress style of southern Mexico, according to Ankori, to conceal her injuries and reinforce her Indigenous heritage.

Kahlo and Diego Rivera, the famed Mexican muralist, were married in 1929. Their relationship was tumultuous and both had multiple affairs. They lived in the United States from 1930 to 1933. In 1938, at time of her first solo show in New York City, Vogue quipped “The rise of another Rivera.”

The exhibition also focuses on Kahlo’s bold explorations of queer, nonbinary, and gender fluid ways of presentation. In a family photo of 1926, the 19-year-old Kahlo fashions herself in a man’s three-piece suit and tie, flaunting a male persona. “Today, her pathbreaking poetics of identity,” says Ankori, “have inspired contemporary artists, musicians, students, people with disabilities, people of color, members of the LGBTQ+ communities, and ever-expanding audiences.”

Frida Kahlo lays out the many creative and powerful ways she wanted to be seen. As her health declined, she continued to dress in her Tehuana costumes and pose by her paintings, at times in her wheelchair. Kahlo told a friend about one of her late self-portrait paintings, Untitled Self Portrait inside of a Sunflower (1954) that if she had to stop painting, she would “wilt like a flower.”

Despite their warranted earnestness, re-collections and Frida Kahlo are exhilarating—the works and their ever-striving creators leap out, individually and collectively, at viewers. The exhibitions place their subjects in a contemporary light so that understanding and compassion can be better exercised.