Studio Visit: Jessica Scriver

Jessica Scriver’s home studio in Charlotte, Vermont, looks west to a stunning view of the Adirondack Mountains beyond Lake Champlain. A camera would capture the vista as a static shot; for the artist, it’s an expression of natural growth, movement, deterioration and reactive change—all elements of her artistic process.

Scriver’s paintings on panel probe how seemingly fixed or predictable patterns can shift, alter and dissolve over time, given their complex embeddedness in an unstable world. A former biology and chemistry teacher, she described

her work as science’s opposite in trajectory. “In science, you get answers that make everything clear. A lot of what I do is exploring the unknown,” she said.

Those exploratory processes are evident all around the studio, from the cement floor’s dense paint drippings to the neatly stored experimental materials that go far beyond a painter’s usual arsenal: embroidery grids, alphabet pasta, iron filings, gel beads that expand in water. The latter “suck up pours,” Scriver explained. “I pour paint, then scatter them to capture movement and motion.”

Containers of heavy body paint share table space with wood-carving tools and some notched trowels she once saw slate-floor installers use in her house. Two works in progress on cradled birch-ply panels—she makes her own at a table saw in the basement—bear blue swirls made with the trowels and sprays of etched lines. Eventually, like the finished works hung around the studio, these two will acquire more layers, a process Scriver approaches intuitively in response to each completed layer.

All of Scriver’s work includes a fixed pattern, often applied using stencils that she cuts, or has laser cut, from sheets of Mylar. Her collection hangs on a rolling clothes rack in a corner of the studio; she built the studio sink from a long shower pan to accommodate cleaning the dress-length ones. Scriver has saved all her stencils; they’re a kind of chronological record of her work, from her first—street maps of New Orleans, Paris, Madrid and Manhattan, made in 2011—to more recent attempts to convey depth through architectural and perspectival grid patterns.

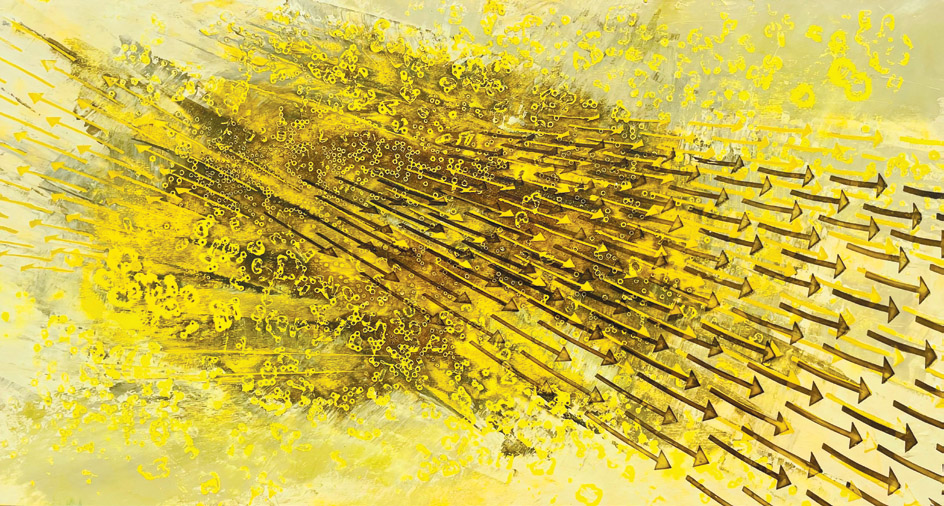

Her latest series, Every Which Way, features stenciled arrows in various shapes and patterns. In some works, the arrows appear to be murmurations of starlings wheeling through textured skyscapes in deep blues and yellows. Others depict volleys of unidirectional vectors that uncomfortably evoke missiles with no clear destination.

“I am on a quest for direction,” the artist writes about the series, “not the kind of direction that can be gleaned from following arrows along a trail, but the kind that is achieved by paying attention to where I have been and holding true to the unfolding of the path ahead.”

Scriver, who is from Ohio, first realized she could make art for a living at age nine when she saw a solo show in Indiana by graphic artist Gustave Baumann (1881–1971), her grandfather’s uncle, who helped revive color woodcuts in the U.S. beginning in the early 1900s. Scriver studied art for a year at Indiana University before a family upheaval led her to transfer to the University of Texas at Austin and change her major to biology. “I needed that stability” of scientific study, she recalled.

While teaching science after college at a boarding school in Pomfret, Connecticut, she returned to making art: She was given free reign of the art teacher’s studio and began taking classes at the Rhode Island School of Design, followed by a summer program at the New York Studio School.

Scriver, an outdoor enthusiast, has led wilderness canoe trips in the remote reaches of northern Ontario for two decades and rides gravel and mountain bikes around Vermont. A college rower and former crew coach, she often brings her single scull to the Lamoille River for early-morning rows. That immersion in nature may account for how her artistic process of building up and breaking down layers echoes natural and human processes of growth and decay.

Yet rarely does her work land on the knowable—say, a solely aerial perspective, or a discrete city, or a suggestion of cellular growth, all three of which she has explored in her work, and sometimes in the same panel. What happens inside Scriver’s frames exists in an untethered space with no discernable certainties—where, paradoxically, she finds comfort.

“It’s all about the control and the lack,” Scriver said. “That’s what drives my creative process.”

Viewers, meanwhile, can have the certainty of seeing her work next in a group show at Furchgott Sourdiffe Gallery in Shelburne, Vermont which represents her, from December 6, 2024–January 31, 2025.