What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine

Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge , MA • nrm.org • Through October 27, 2024

In a fraught election season, this retrospective on the art of pioneering counter-cultural MAD magazine illustrates how laughter can be a tool for social and political change. Co-curated by the Rockwell’s chief curator Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and illustrator/art journalist Steve Brodner, it showcases over 250 images by more than thirty artists in a dense, yet comic, multilayered exhibition that says as much about artistic collaboration as it does about lampooning American culture.

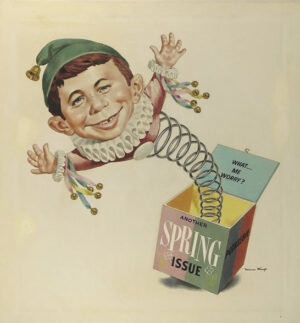

Launched in 1952 by editor Harvey Kurtzman and publisher William Gaines as an EC comic book series, MAD was converted to an illustrated magazine in 1955 to skirt potential censure by the industry’s Comics Code Authority. Aimed at young readers with a goofy, gap-toothed cover boy named Alfred E. Neuman as a ubiquitous presence, MAD hit a peak circulation of over two million in the 1970s, despite lawsuit threats and an FBI investigation. After 585 published issues, it continues today in curated reprints and a legacy of late-night television comedy.

Illustration art is story-driven, so viewers will scan hundreds of captions, narrative bubbles and wall texts as they navigate work by generations of artists, including a few women, who contributed to MAD. Theirs was a world in which writers pitched story ideas as blocked-out movie scripts that artists were later hired to visualize.

“It was done with tremendous care and skill,” said Brodner of the discipline required to take narrative direction and come up with arresting images on tight deadlines.

Mash-ups of subjects that do not normally go together mock correctness. Richard Williams’s substitution of MAD’s Neuman for the figure of Norman Rockwell in the latter’s 1960 Triple Self Portrait or the gorilla face Roberto Parada put on Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring are two examples.

Superbly drawn caricatures by Mort Drucker reprise the political power of the Sixties-era Kennedy family and the criminal reach of the Italian mafia in the 1972 film The Godfather, renamed “The Odd Father.”

By the 1990s, digital technology made pictorial changes easier and cut production time, though made “dinosaurs” of human artists, complained Brodner, saying, “no robot could do what they did.”

— Charles Bonenti