Wiley Holton

I first met Wiley Holton in her lovely home studio joined by her two cats; she is an early career artist based in Medford, MA, colliding painting and math. Her meticulously made acrylic and graphite paintings on panel vary between multiple series, two of which are her kaleidoscopes and horizon lines. Each employs gradients and subtle color mixing to formulate elegant paintings. A Massachusetts local, Wiley Holton grew up in Dedham, MA, and went on to attend Colby College in Maine. There she studied studio art with a minor in mathematics graduating in 2019. Her paintings are in private collections from Las Vegas, NV; to Denver, CO; and Sydney, Australia. In 2019, she received the President’s Purchase Prize for her painting Circumferences of the Void, 2019, which is now part of the Colby College Museum of Art’s permanent collection. Since school, she has transitioned to making art full-time, working on a variety of paintings and commissions helping to drive her practice forward.

In her studio, we are greeted with her tabletop easel surrounded by small containers of paint where she works intensely on her kaleidoscope paintings. This series includes paintings on gradient surfaces and others on flat colors. Here she employs the principles of kaleidoscopes, building them on acrylic-painted wood panels. Holton breaks up the kaleidoscopes on the surface of the painting, mapping them out with short intersecting lines, pausing, and restarting in different places across the panel. These form an unmistakably mathematically driven and intensive process that leads to a delicate and intimate viewing experience. Her painting Drifting, 2023, acrylic and colored pencil on wood, 36 x 48 inches, shows colliding lines overlapping in short segments to form the radiating triangulating shapes looking like solicitations vanishing at sunrise. White-colored pencil overlays acrylic painted in gradients. Moving from the rich matte navy left side to the right with paling blues turning to a cool grey early morning sky. Over top using a compass and measurements, Holton creates the lines, driving small holes into the panel’s surface from repeated pressure. In these holes, she fills in hot pink paint, one of the most enticing little surprises in the work. Stepping back from Drifting, we see the even gradation of paint forming halation: where the abutting edges of the various stripes of color cause them to appear to shift across the stripes with the edges looking brighter on the dark side and darker on the lighter one. An optical illusion transpires below the solid lines highlighting the atmospheric nature of the paintings meeting the mathematically geometric forms with intuition and optics. Photographs do not capture the subtlety in Holton’s work—necessitating an in-person viewing.

Other works like Rule of Thirds, 2022, acrylic and graphite on panel, 36 x 48 inches, split into two parts, the top third white and bottom black. Using only graphite over the paint below, the thin lines shift unexpectedly. Over the black portion, the pencil looks glowing and silvery, while the top white portion forces contrast making it appear black, despite being all the same. These subtle shifts and optical mixing present in Holton’s work only come out upon close looking.

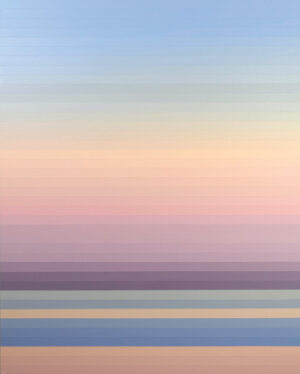

Walking through Holton’s home and studio tours her painting practice and history of making. Moving from earlier works made in her final year at Colby College to brand new paintings, and ones yet to be finished. Her studio shows the evidence of her practice with small tubs of paint labeled by color code, a number and letter, mixed ahead to be applied in a specific order. In her horizon lines, she mixes colors shifting from dark to light, saturated to muted, and warm to cool. Without being overly descriptive or complicated these paintings expertly imply the horizon—a sunsetting at the beach or Badlands National Park. Cloudless Coastline, 2022, acrylic on wood, 20 x 16 inches, shifts from light blue at the top down to sandy peaches and the water’s edge with muted blues reflecting the sky color. Using only line and color, Holton suggests an entire landscape and time of day.

Holton’s work is by far best experienced in person, where you can see the subtle shimmer of graphite, and get close enough to see the small holes drilled into the panel’s surfaces by her compass. You can see her work in person with Scott Stropkay at the Concord Art Association from May 2–June 2, 2024, and join the reception on May 16, 5:30 pm.