Summer With the Averys: Milton, Sally, March

By: Charlotte Foote

Walking through the Bruce Museum’s Summer with the Averys, you’ll see a number of Milton Avery’s iconic works on display, typically bold in their rendering of color and abstracted figures. You’ll see seascapes and landscapes and swimming pools and riverbanks. And, as in many of his paintings, you’ll often see two women: his wife, Sally Michel, and his daughter, March, both of whom often served as his subjects. What’s different about this exhibition is that you won’t just find the Avery women within the bounds of Milton’s canvas, remembered only by his brush. Here at the Bruce Museum, the work of all three Averys hangs together, side by side.

If you haven’t heard of Sally Michel or March Avery, you aren’t the only one. Kenneth E. Silver, the curator of the exhibition, wasn’t too familiar with either until speaking with a private dealer about the show. Silver didn’t actually begin the curation process with “the self-conscious idea” that he would do a show about the Avery women at all. “I knew of Sally Avery as an artist, and I’d heard of March Avery, but I was completely unaware that she also was an artist, let alone that she was alive and well and still active as a painter,” he said. Only after visiting March and seeing more of Sally’s works in person did he realize their remarkable, largely unrecognized talents as individual artists. With that realization, the concept of a family exhibition was born.

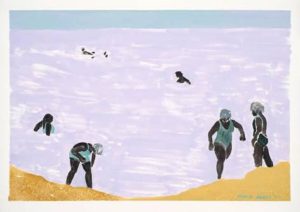

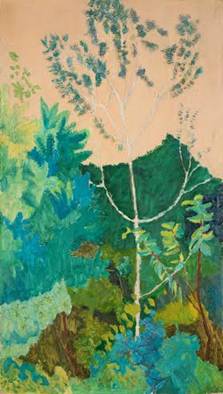

For the Averys, summer was a “working vacation”—not just an opportunity for enjoyment, but also one for “research.” The trio traveled for months at a time, often making sketches, watercolors and gouaches along the way. Untitled (Beachgoers) by Sally portrays a beach scene sketched in pencil with each element labeled by color: “navy blue” is scrawled upon the bathing trunks, and “yellow-green” upon the umbrella. Works like these were often brought home and made into oil paintings during the wintertime—and many stand as finished works on their own. In The Dead Sea, March depicts teal-bathing-suit-clad women swimming and wading in lavender waters, the sunlight gleaming on the surface aptly captured by the lightness of gouache and watercolor. In Milton’s Thoughtful Swimmer, watercolor serves as a layering tool, dense and bold where the shadows are, translucent where the light shines through the leaves and onto skin.

This exhibition provides a rare opportunity to see the way each artist’s work relates to the rest of the family. These artists weren’t just part of the same movement. They weren’t merely contemporaries. They were living under the same roof, visiting the same small forest stream and painting next to one another. The resulting similarities don’t stop at a working strategy of drafting in nature and later translating to oil. Walking around the gallery, you’ll see subject matter from the same location painted by all three artists. You’ll notice a shared color palette that runs through their collective works, sometimes rich and earthy, sometimes an airy array of pastels. Milton’s famous use of color in large, flat swaths as well as his faceless, abstracted figures are echoed in the works of Sally and March, also. They were not mere emulators of Milton’s paintings, however. There was a shared style within the family which morphed into particular forms at the hand of each artist. Although their work is similar, it is certainly not the same. One of the joys of this exhibition is to see how the world differs through each artist’s eyes—how bodies and trees take on different forms, how particularly the ocean moves depending on where one is sitting. When so much of life and work is shared, it is these small things that seem suddenly paramount.

Summer with the Averys is, in many ways, simply about the resplendence of summertime. The paintings glow with warmth and never rush—they linger by the sea in late afternoon on beach towels, they swim naked in rivers and doze off in the sun. These works are rich and to be savored first and foremost. But this exhibition also harkens the often-quoted adage, “behind every man is a great woman.” In this case, there are two women, both of whom have been largely forgotten in Milton Avery’s rise to fame. Sally Michel worked for many years as a commercial illustrator, earning the primary source of income for her family so that Milton could pursue a career in fine arts. Some of her sketches are displayed in the exhibition. Although March said that her mother didn’t see herself as a “martyr,” there’s no doubt that her work was a sacrifice for the sake of Milton’s growth. Stephanie Guyet, the Bruce Museum’s current Zvi Grunberg Fellow, assisted Silver in organizing the exhibition, and was “key to [his] understanding much more fully what the life of a woman in the art world might be.” With the help of a woman, these women were brought into the light. And the truth is, although fame has placed their names behind Milton Avery’s, they were never truly behind him at all. They were right there beside him, brushes in hand, painting the world together.