Ernest Withers: A Second Look

When visual arts make national news, it’s usually because of a newly discovered masterpiece, an outlandishly expensive sale, or a forgery. But how often does art news include the FBI and make us reconsider an artist’s body of work? This happened to me recently when looking through Let Us March On! Selected Civil Rights Photographs of Ernest C. Withers 1955–1968. One photograph, in particular, shifted meaning before my eyes. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lies in state at R. S. Lewis funeral home. Memphis, TN. 1968 shows King lying in his casket.

When visual arts make national news, it’s usually because of a newly discovered masterpiece, an outlandishly expensive sale, or a forgery. But how often does art news include the FBI and make us reconsider an artist’s body of work? This happened to me recently when looking through Let Us March On! Selected Civil Rights Photographs of Ernest C. Withers 1955–1968. One photograph, in particular, shifted meaning before my eyes. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lies in state at R. S. Lewis funeral home. Memphis, TN. 1968 shows King lying in his casket.

He wears a dark suit, his arms tucked to his side, his eyes closed deeply in the poise of final repose—in stark opposition to the tragedy of his murder. Heaven-white bunting frames his body. In the left foreground of the image, a Caucasian photographer—his back to the viewer, but close enough to see his thinning hair—holds out a light meter as he adjusts the settings.

Clearly the issues of light and dark, life and death, white and black are being measured here. It is a photo rich with narrative and tortured with history. But it also is a metacommentary on King as a media magnet and those who stepped over all sorts of lines to get at him, even in death.

As it turns out, Withers may have stepped over some lines, too. Until last year, Withers had an unshakeable place in the history of civil rights photography. In addition to King, his subjects were Emmett Till, James Meredith, Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, as well as countless other African Americans who bravely marched, demonstrated, voted, carried signs, sat in segregated restaurants, and enrolled in segregated schools to end injustice.

But last September, on the eve of the opening of an exhibition of his work in Memphis, Tennessee, where Withers was based before his death in 2007, a story in the Commercial Appeal revealed that Withers may have been working double duty: a behind-the-scenes photographer with enviable entrée, and a so-called “racial” informant for the FBI.

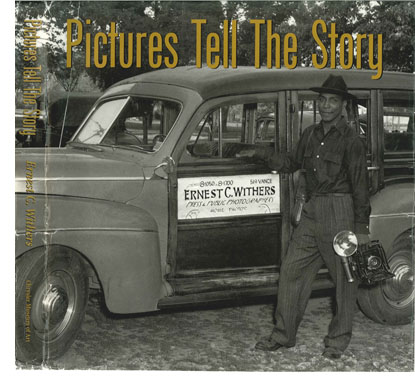

This is not the first time the photographer’s name and the FBI have appeared in the same place, says Tony Decaneas, who was Withers’s exclusive agent and partner from 1992 through the beginning of 2011. In Pictures Tell the Story, the monograph for the 2000 Withers exhibition at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, the photographer revealed he had FBI agents regularly looking over his shoulder and questioning him. “I never tried to learn any high powered secrets,” Withers said. “It would have just been trouble.…[The FBI] was pampering me to catch whatever leaks I dropped, so I stayed out of meetings where decisions were being made.”

“I dismiss it as not very interesting news,” says Decaneas, who is also founder and former owner of Panopticon Gallery in Boston. “Why is this news? I was astounded by the brouhaha. Ernest was a former policeman and served in the army. He was familiar with law enforcement and would have freely shared information if someone’s well-being was threatened. But he would not have compromised anybody in the movement itself. I don’t believe that for a minute.”

And yet something about seeing the FBI files has cast the very dimmest patina of suspicion on Withers’s legacy.

After hearing the news officially reported last year, I found myself asking two questions, one about the way we see art, and another about the way we see artists. First: Does it change the art if we perceive the artist’s political actions as betraying our faith in his intentions? Second: Do we grant absolution—a pass—to an artist of immense social significance because it is unimaginable to many that he could have been working for the movement and working against the movement at the same time?

“I’m not certain I fully believe he was working both sides,” says Callie Crossley, a producer, writer, and director for Eyes on the Prize, the award-winning 1986 PBS documentary series about the civil rights movement. Crossley, host of her own talk show on WGBH radio in Boston, also grew up in Memphis where Withers was a fixture of community life.

“At the time of the civil rights movement, the FBI was something to be skeptical about,” says Crossley. “That’s why this has such deep meaning if it’s true. You can cut the value of his work three ways: a documentary of the community of Memphis, a documentary of the civil rights movement, and a documentary of people whose lives were not in the mainstream or public sphere. The work is valuable whether he was connected to the FBI or not. But for some—and me, too—if he worked for the FBI, it would be very disappointing.”

Although the media hasn’t exactly been saturated with this news of Withers, stories have continued to circulate about the charges and whether or not his work and life still hold the same power. CNN’s Soledad O’Brien devoted a segment of Black in America to Withers’s tricky legacy. In the show, descriptions of Withers—once loaded with iconic heroism—slide into another tone: “piercing,” “snitch,” “Judas.”

Very few reporters, however, mention the art—beyond its comprehensive documentary nature. And yet the art is where I find myself landing each time I see a new story. As Crossley says, the charges are too inexplicable to face. As the sesquicentennial of the Civil War looms, it’s also likely that history will be bent and shoved through many a revisionist lens. Is that the case with Withers, whose works Margaret Walker, the scholar and novelist, compared to poetry?

Very few reporters, however, mention the art—beyond its comprehensive documentary nature. And yet the art is where I find myself landing each time I see a new story. As Crossley says, the charges are too inexplicable to face. As the sesquicentennial of the Civil War looms, it’s also likely that history will be bent and shoved through many a revisionist lens. Is that the case with Withers, whose works Margaret Walker, the scholar and novelist, compared to poetry?

When I mentioned the Withers case to a talented student videographer at Harvard, she responded: “My value for Withers’s work will be decimated if it is proven that he was in fact a paid FBI informant because manipulating individuals (civil rights leaders, in this case) under a façade of ‘art’ simply defies the crux of being an artist—to influence society in a personal, expressive manner for the betterment of society.”

Whether he worked for the FBI or not, Withers did influence society. He did help make it better. But must an artist also be an upstanding citizen? Withers wouldn’t be the first—or the last—artist in history whose ratio of politics to arts is skewed. Consider the poet Ezra Pound, charged with abetting fascism, and film director Leni Riefenstahl, propagandist for the Nazis.

“I am very impressed with the strength of his work by combining strong formal qualities, a keen sense of the historical significance of the subject matter, and the subtleties of the human species—all of which adds up to a very solid body of work,” says Glenn Ruga, executive director of the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University. “In the arts, I believe we need to accept the humanity and frailties of human beings. Not all artists can stand up to the state, certainly not a black man in the 1950s and ’60s in America.”

Bill Chapman, a photographer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, followed another side of Withers’s career: his photographs of Negro League Baseball. (Withers also photographed musicians.) For five years before he died, Withers was a mentor to Chapman, and the two became very close—or, as Chapman says, like father and son.

“Absolutely he was a patriot, and he was a witness to history,” says Chapman of his artistic role model. “He would not support anything disruptive in a violent way. He was opinionated about everything. Violence and violent people were among the things he would rail against.” And here Chapman pauses. “But I never asked anything of him.”

That photograph of Dr. King stays with me. There are those who say that if Withers really were a snitch, King would have somehow understood; that somehow Withers would have been making deals to secure rather than threaten civil rights. If that’s the case, Withers took his methods and secrets to his grave. Others can’t get beyond the incomprehensible liaison—even considering that Withers sometimes didn’t get paid or was paid meagerly, and had eight children to feed.

The works that now hang in the Ernest Withers Collection Gallery & Museum, which opened last year in his former studio on Beale Street in Memphis, tell a complex story, both at the scene and behind the scene. “The story his images tell is true and relevant,” says Michelle Lamuniere, a curator of photography at Harvard Art Museum. “I took note of the news, but it doesn’t change the important narrative of his work.”

The art has not changed. But what we see in the art—and the artist—is a story that

continues to shift. ■

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alicia Anstead is editor-in-chief of Inside Arts magazine and the Harvard Arts Beat blog. She is also arts commentator on WGBH Radio in Boston. She can be reached at www.AliciaAnstead.com.