10 Emerging New England Artists

A Power Panel of Seven Selects a Provocative Ten

Destiny Palmer

Anna Mcneary

Harlan Mack

Gabriel Sosa

Adèle Flamand-Browne

Margaret Jacobs

Asata Radcliffe

Sumru Tekin

Ryan Adams

Nancy McTague-Stock

What do we mean by emerging? It can easily carry different meanings, depending on the moment, context and, in this case, the nominator. For the 10 artists selected here, while each is fully engaged in a well-developed artmaking practice, their work commands attention—by the art-viewing public, art institutions, galleries, across New England and beyond. The artists selected by this year’s seven nominators speak to issues of racial, gender, and socio-economic equity in surprising and compelling ways and through diverse media—from text-based billboards to immersive outdoor installations. They speak to nature, the past; to hope and darkness. These artists speak across age, gender, race and cultural identity, representing a true zeitgeist of our time. Some you may know, others you may not. We’re excited to introduce them to you.

Maine-based Ryan Adams’ tagline is “Ryan Writes on Things,” and he does—applying text and brilliant geometries on everything from buildings to signs to paintings. Adèle Flamand-Browne is fresh out of a BFA program at Lyme Academy College of Art, where she found her voice in figurative realism. Enfield, New Hampshire-based Margaret Jacobs, member of the Akwesasne Mohawk Tribe, creates culturally evocative large-scale sculpture and jewelry fabricated from metal. Harlan Mack explores a single narrative across multiple bodies of work in both metal sculpture and painting from his home in Johnson, VT. Anna McNeary, of Providence, RI, addresses questions of equity in her performance art, textiles, and printmaking. Nancy McTague-Stock is well-established as a teaching artist throughout New England and New York with a decades-long practice in printmaking. Boston-based Destiny Palmer interrogates colonialism through her thought-provoking installation, painting, and public murals. Portland, ME-based Asata Radcliffe speaks to her racial and Indigenous identities through her futuristic, multi-sensory installations. Gabriel Sosa, living in Boston, MA, has reached audiences in powerful new ways through his text-based billboards. And Vermont-based Sumru Tekin, a multi-disciplinary artist, works in a range of media with which she re-contextualizes the found and constructed—from drawings to photographs to texts.

This year’s artists were nominated by a fascinating group of art professionals: curators, artists, and teaching artists—several serving in more than one of these roles. We’re grateful for their time, their conversation and for their consideration of what constitutes “emerging”: Camilø Álvårez, owner, director, curator, and preparator at Samsøñ, in Boston, MA; Rachel Moore, executive director and director of exhibitions, Helen Day Art Center in Stowe, VT; New York-based Patricia Miranda, artist, curator, educator, and founder and director of MAPSpace and The Crit Lab; Julie Poitras-Santos, director of exhibitions, Institute of Contemporary Art at MECA; Jami Powell, associate curator of Native American Art at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College; and Francine Weiss, senior curator, Newport Art Museum.

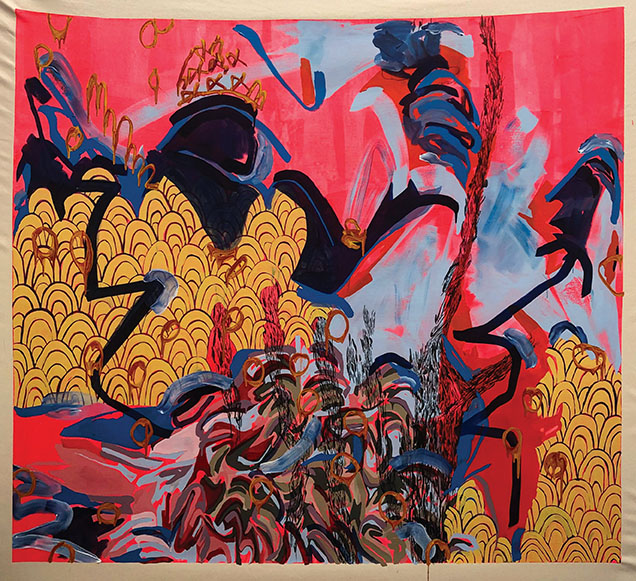

DESTINY PALMER

BOSTON, MA

“As an educated woman educating, she is specifically in tune with emerging audiences. Destiny Palmer’s works fill a need for scale and color in abstraction. In addition, her series, Labored Bodies, links the enslaved past with the present morass and hopeful future,” says Camilø Álvårez, owner, director, curator and preparator, Samsøñ.

Destiny Palmer is increasingly sought after for public art projects in Boston and beyond, yet she maintains a commitment to community engagement at home. Formerly an assistant professor at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, she now teaches at Thayer Academy in Braintree, MA, while remaining fully engaged in her art practice. “For me, painting is my language,” she says, whether she’s working on canvas or the front of a building.

Palmer’s Labored Bodies series explores America’s colonial history, directly confronting slavery and its continued reverberations. In her installation Weary, for instance, swaths of cotton and layers of fabric rest upon a chaise lounge between a sea of colorful yarn tufts on the floor and a curtain adorned by a brilliantly hued abstract painting, the cotton symbolic of the slave labor that produced it. Aesthetic themes from the series carry over into her abstract expressionist paintings, which she sees as responses to the intensity of the Labored Bodies works, serving as “reactions to whatever I’m researching.”

Fabric and pigment have deep and complicated histories, Palmer reveals, and as such serve as another means of having a conversation about the past. The cotton duck in painters’ canvases is a tool, one she makes use of—yet it also represents exploitation. As Palmer puts it, “My family roots are drenched in cotton picking.”

Palmer’s mural work conveys similar messages. “Mural work is really a powerful place for me. One, it feels like a moment of reclamation,” she says, pointing out “how few women are asked to participate. And how few women of color are asked to participate.” She hopes to drive home that message by painting the mural herself, not just designing it: “There’s something really powerful when you’re on a scaffolding or a scissor lift trying to paint a 19-foot wall. You need to see me up there to recognize that this is what people that look like me could do.” — Julianna Thibodeaux

Anna McNeary

Providence, RI

“Working in textiles, printmaking, sculpture, drawing, and performance, Anna McNeary creates compelling and thoughtful works that reveal the hidden labor of women and examine the complex social and political relationships amongst people. While her work is visually stunning, it also subtly challenges a viewer’s complacency. Whether stitched, woven, knit, printed, drawn, or performed, McNeary’s works of art prompt viewers to consider and contemplate issues related to social justice, history, identity, and psychology,” says Francine Weiss, senior curator, Newport Art Museum.

Anna McNeary wasn’t sure she wanted to commit to being an artist until after she earned her undergraduate degree in sociology, when she realized she wanted to take what she had explored as an undergraduate and turn it into art. She was interested in gender, race, and class, and wanted to explore their intersections through artmaking. So she returned to school for an MFA in printmaking at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). “What my sociology degree did give me,” she says, was the desire to use art “as a means to articulate nebulous and complex social issues and ask questions about those things.”

RISD set her firmly on that path, one she continues today. From image to material, her work has evolved to focus on process. “A lot of viewers read symbols of femininity in my work,” she says, whether due to the soft materials such as yarn or the traditionally gendered practices such as making apparel—and using “lots of pinks.” As she says, “It’s not that gender is absent from my work, but also, what is the feminine?” As her work continues to evolve, she hopes it will continue to challenge viewers thinking about “how elitism, classicism, racism, and sexism shape the way art is made, and the spaces in which our art is made.” From her textiles to her performative pieces involving the community, she says, “I want people to be able to sit with my work and think about it from multiple angles.” — J.T.

Harlan Mack

Johnson, VT

“Harlan is a prolific artist who has a compulsion for creating. The layers and depth in his work, both conceptually and in materiality, pull the viewer into his story, whether fictional, personal, historical, or utopian. The work is physically gorgeous and robust with a laborious and richly textured presence of the hand. Yet it is ultimately his thoughtful curiosity and the exploratory nature of his work that continues to draw one in to see what he’ll do next,” says Rachel Moore, executive director and director of exhibitions, Helen Day Art Center.

Self-described as a “rural multi-disciplinary artist,” Harlan Mack contemplates fictitious futures through his narrative-based artmaking, whether through sculpture or painting. Mack’s worldview is informed in part by the fact that, even though he has spent most of his life in Vermont, as a child he moved around a lot: “My dad was a bit of a wanderer,” he says. While pursuing his MFA at Johnson State College he realized that all of his work seemed to spring from a single story coming from a single world, which was apocalyptic. This surprised him, because, as he says, “I don’t believe in an apocalypse.” But the apocalyptic images persist to this day, and the storyline continues through different bodies of work. “I built this complex world that I couldn’t possibly have created in a linear fashion,” he says.

As he traveled around with his filmmaker father as a child, he also lived off the grid for a time, and recalls watching movies on a small black-and-white television powered by a car battery. Mack connects earlier experiences such as this one, with its apocalyptic undertones, to his current work. In one piece, he found himself painting a giant octopus, although he wasn’t sure why it was there. As the painting developed, the narrative evolved, too: the octopus “deifies itself,” he explains, while humans place their unwanted emotions into “rage tanks,” orb-like images that mirrored the steel ball sculptures Mack was making at the time. In this world, “Everybody had one,” he said, like an iPhone.” — J.T.

Gabriel Sosa

Boston, MA

“Gabriel Sosa is translating immigrants in court and then, with his current works, relaying those stories and sentiments into the public realm. We all need those who can critique the institutions with mirth and menace,” says Camilø Álvårez, owner, director, curator and preparator, Samsøñ.

Self-described as “an artist, linguist, and educator whose practice is rooted in the cross-section of law, translation, social justice, and the synthesis of fact and fiction,” Sosa creates across multiple disciplines to explore the way language shapes experience. In all of his work he invites viewers to contemplate the role of language in unexpected ways.

Growing up in a bicultural home in Miami, FL, sparked his interest in language early on, eventually leading to work as a court translator in Boston—work he continues today. “So many times, victims will come searching for understanding, for some sense of justice, and they don’t find it there,” he says. Often, these issues are “buttressed by socioeconomic differences.” Sosa responded to these realities in his most recent public art series as one of three Boston-area artists chosen for Now+There’s Public Art Accelerator Program in 2020. His It Ain’t Easy series of nine billboards, displayed between July 2020 and January 2021, “were these ambiguous messages of hope that went up both in English and in Spanish across Boston in neighborhoods that have been most severely affected by COVID-19,” he says, due to the fact that they have high concentrations of immigrants and frontline workers. [Many of these billboards can be viewed in his Instagram feed.]

Sosa explores similar ideas through drawing, installation, video and, more recently, sound. “That is something that has interested me more and more,” he says, “how sound affects our life and how it conditions the public spaces we experience.” As an arbitrator of our experience, sound can be perceived as yet another iteration of language. Currently in the midst of another artist residency at Urbano Project in Jamaica Plain, MA, Sosa hopes to help youth harness language through “the power of the gesture,” he says. “This can be a note you leave in somebody’s mailbox. Or this can be a message you write in the snow.”— J.T.

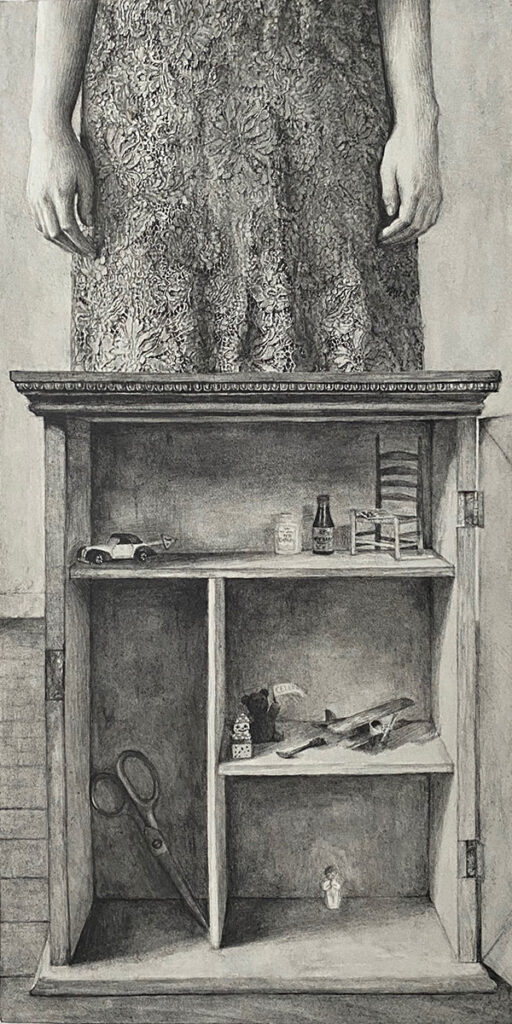

Adèle Flamand-Browne

New Milford, CT

“The first effect of young artist Adèle Flamand-Browne’s uncanny graphite drawings is her enormous skill. Yet skill is not art; her anxious self-aware gaze on adolescent girls and burgeoning young women resonates long after the initial verisimilitude. Flamand-Browne’s work references the language of photography, stage set, film noir, capturing the dread and anticipation of both Hitchcock and the fraught space of growing up on today’s social media,” says Patricia Miranda, artist, curator, educator, and founder of MAPSpace and The Crit Lab.

Adèle Flamand-Browne’s art represents a simpler time in history. Her compositions include farmhouses, wide plank floors, and scary attics that hold a place in our memories. At first glance, many images could be mistaken for black-and-white photographs. She is the model in most of her illustrations and even her style of dress feels purposeful and vintage. The echo of nostalgia is intentional, in both her subject matter and technique. Here form and function meet as she applies water to powdered graphite and uses makeup brushes to render lifelike, haunting complexions. “It works with me, so I’m working with it,” the artist said.

A recent graduate of Connecticut’s Lyme Academy, the artist focuses on figurative forms and naturalistic depictions. To break with her peers, Flamand-Browne wanted to illustrate more than celebrities and existing photographs. She preferred to control the person within the image and to achieve this, added art director and set designer to her resume. This additional measure allows her to play with shadows and add to the likeness of the subject.

Within her luminous images, the study of creases is pronounced—the linen on a pillowcase, the bend of a knee, or a wrinkle in the skin. The only hard lines to be found are in the architectural elements. In her series focusing on structures, the buildings become the subject of her portraits rather than people. The artist depicts dwellings much like she does bodies in relation to how they age and deteriorate. In Beyond Usual, a stand-alone decrepit house exemplifies the destruction of the nostalgia she’s trying to create. “[An old house] shows time, it shows character, it is a familiar thing… you don’t have to know who lived in it to relate to it in some way.” — Jennifer Mancuso

Margaret Jacobs

Enfield, NH

“Above all else, Jacobs is a storyteller. She uses her sculptural works as a means to participate in the creation and perpetuation of visual narratives that explore the multiplicity and complexity of human experiences, and particularly those of her own nation, the Akwesasne Mohawk. Jacobs’ steel sculpture and jewelry often feature bold lines and stark contrasts in color—applied through powder coating—alongside more delicate forms and natural materials,” says Jami Powell, associate curator of Native American Art, Hood Museum of Art. “Rather than avoiding the contradictions and tensions that characterize our world, Jacobs’ artistic practices dig in deeper and invite us to sit with and even find comfort in ambiguity.”

Margaret Jacobs employs metalworking in unexpected and provocative ways, telling stories through both materiality and method. Jacobs traces her metalsmithing practice to the iron worker history of her community and her roots as a member of the Akwesasne Mohawk nation in New York state, more often associated with Black Ash splint and sweetgrass basketry. These influences come into play, too, yet working in metal, she says, is “the thread that connects all of my work.”

The resulting sculpture and jewelry reference the natural world and organic processes, offering up a dance between fragility and strength. In her most recent sculpture series, larger-than-life wrench forms are suspended with charm-like objects such as antlers, feathers, and leaves—all crafted from metal. “Overall, a lot of my work is speaking about nature and natural cycles—growth, birth, decay,” Jacobs says. “While that’s happening with the physical object, you’re also thinking about it conceptually.”

Whether sculpture or jewelry, her work is all hand-cut. She applies color through a powder-coating process in which pigment is integrated into the surface of the metal. “There’s this really interesting material shift that happens once you go through that process,” she says. The results are seamless, allowing Jacobs to incorporate hues that lend a softness to the hardness. As she puts it, “I’m trying to create balance.”— J.T.

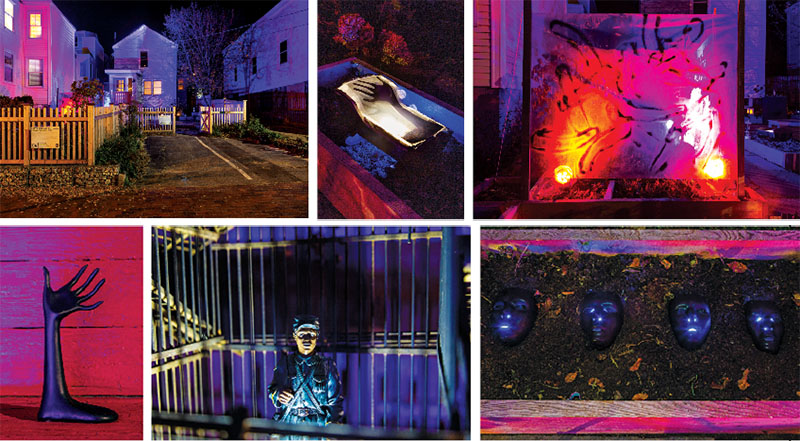

Asata Radcliffe

Portland, ME

“Asata Radcliffe’s multimedia work draws on her background as a writer of speculative fiction and her interest in connecting ancient knowledge with futurism. Her recent works draw from history to help us think forward, making visible, and connecting us to, the WWII Black Guards of Maine, Black Civil War soldiers, and Indigenous histories. Radcliffe invites viewers to imagine a new future that more fully acknowledges our past,” says Julie Poitras-Santos, director of exhibitions, Institute of Contemporary Art at MECA.

As a multi-media artist, Asata Radcliffe merges writing, research, and imagining the future to create installations that are driven by, as she describes, “a fusion of Black and Indigenous cosmologies paired with a lifelong dharma practice.” Working in installation, she says, allows her “to connect the audience to the future and/or past in a way that is speculative and experiential.” To that end, she produces what she calls “sets”—spaces that people physically enter and, Radcliffe hopes, “provoke spatial destabilization that leads to a visceral understanding of the story being told.” Using props, video, and sound combined with historical items and what she describes as “crafted speculative/futurism objects,” her aim is “to tell the story of timelessness and the cyclical nature of the human experience.”

Her first outdoor installation, A Slower Ontology (in partnership with SPACE Gallery), engaged the public in a new way for Radcliffe: “BIPOC didn’t have to worry about encounters of being policed by art gallery security, which happens quite a bit in art galleries.” In this installation, “the imprint that I created was a speculative, surrealist, and haunting reality,” which “set the tone for an aesthetic that will continue to evolve.”

At publication, she was completing her most recent work, a site-specific installation created in collaboration with other Maine BIPOC artists at UNE-Portland. Like her previous installations, it explores a speculative future. In particular, what will Maine look like in the year 2221, from the Indigenous and African diasporic perspective? The installation will converse with the exhibition of African masks from the collection of Osar Mokeme, the two connecting through the embodied history of the African diaspora and original homeland. — J.T.

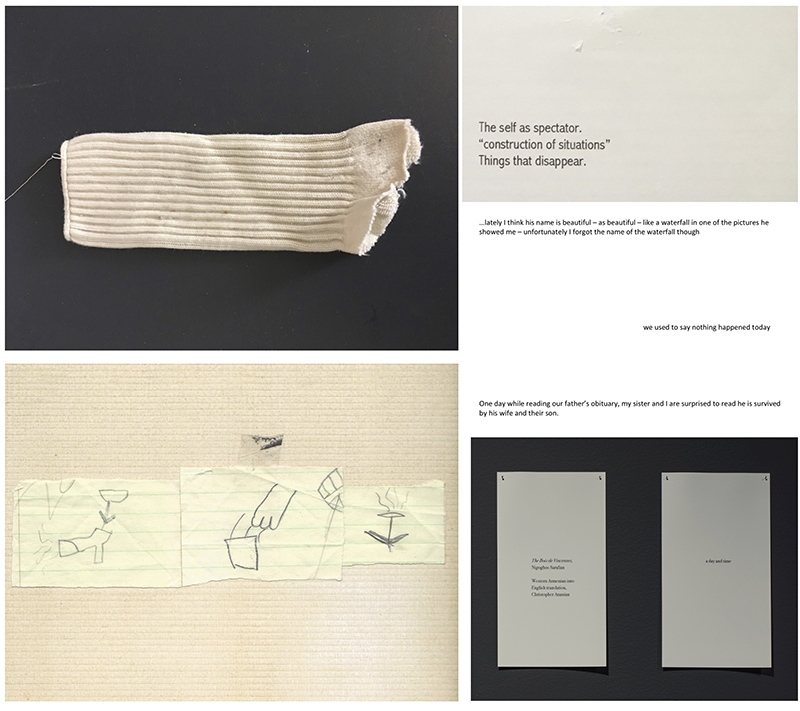

Sumru Tekin

Charlotte, VT

“Sumru Tekin’s work fractures narratives through interrupted layerings of film, sound, photography, and installation. Born in Turkey and living in Vermont, Tekin explores uncertain notions of memory, history, and time; how the inability to concretely know them simultaneously constructs and undermines our collective and individual identities. Her inchoate visuality is heard and felt as much as seen, like water lapping against a shore, rushing, pooling, looping back, incomplete, parts dissolving in an unsettled interiority,” says Patricia Miranda, artist, curator, educator, and founder of MAPSpace and The Crit Lab.

Touring Sumru Tekin’s website is part museum excursion and part field study. “It’s sort of a laboratory for my thinking and my work and it just so happens to be public,” she explains. Her site, her “cabinet of curiosities,” includes poetry, photographs, audio, and video allowing the viewer to click through leisurely. In describing her work, the artist reveals she is interested more in the questions of things rather than the answers. The end result is a series of attempts at uncovering the question. The hope being that the viewer mimics her process.

The artist, who received her MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts, was born in Turkey and has lived in Vermont now for 30 years. As a Turkish woman, she indirectly explores the difficult subject of the Armenian Genocide and Turkey’s subsequent denial of the events in her installation, One Day. Her website installation, Spectator, is a series of images, quotes, poems, and audio that has the feel of an auditory storybook. Spectator showcases Tekin’s role as a record keeper, blending found objects like a frayed sock, with that of an early postcard of Turkey. Independently, these images serve as a progression, like easily digestible courses of an elaborate meal. Merged together, the poem and texts create a feast laid upon a long banquet table where guests can revisit favorites over and over. “I hope my work is open-ended and these narratives and stories are inconclusive and allow for the viewer to make their own connections.” — J.M.

Ryan Adams

Portland, ME

“Ryan Adams’ work has animated public space throughout Maine and beyond for over a decade. His background in traditional graffiti led him to creating vibrant, geometric large-scale mural works that often include text hidden within them; these messages are visible to those who slow down to look more deeply into the meaning of the works,” says Julie Poitras-Santos, director of exhibitions, Institute of Contemporary Art at MECA.

A few weeks after leaving his corporate job of 10 years and days before the COVID-19 lockdown, Adams took a leap of faith and turned to art-making full-time. Jobs were on the books—murals, brewery commissions, hand-painted signage—he felt secure and excited. And then lockdown. “It was terrifying,” he says. “I thought I’d just ruined our lives.” With projects on pause, Adams went into his studio, “drawing and painting to process emotions,” and created the digital piece We Gonna Be Alright, inspired by a Kendrick Lamar song, and which is currently part of the Untitled show at Portland Museum of Art. “It was the mantra in my head during those first weeks.” As he pushed forward, the bigger picture came into focus, similar to how our eyes do when gazing at Adams’ graffiti work.

Born and raised in Portland, ME, a self-proclaimed “letter nerd” and a child of hip-hop culture—“It’s embedded in every piece that I do”—Adams pays his success forward and is devoted to his community. In spring 2020, Adams was invited to paint a mural of George Floyd in downtown Portland, the 6 x 9′ mural going viral amidst the protests, and coming to the attention of Floyd’s family. Adams and his wife, textile designer Rachel Gloria Adams, also started the Piece Together Project, a series of murals of local residents. Drawing from his graffiti writing background, Adams’ “gem” style letter works go big and bright, packing power and wit. Colors and patterns pop at sharp angles, swirling in color variation and shadow—overwhelming at first until the letters come into focus and the words emerge, their meaning becoming clearer. As did Adams’ leap of faith. “It was meant for me to take that leap at that moment to bring my work to where it is now.” — Rita A. Fucillo

Nancy McTague-Stock

Wilton, CT

“Nancy McTague-Stock transmutes her intimate connection with nature in a variety of recombinant media. By marrying painting, photography,

drawing, and printmaking (solar prints, drypoints, monotypes) she reveals hypnotically enigmatic images. The work invites close scrutiny. McTague-Stock presents rhythms of nature as they appear in micro-patterns and native color harmonies. Her work vibrates with such tender subtleties that you feel beckoned to join her dancing forms,” says David Dunlop, landscape painter and art blogger.

As nuanced and layered as her work, Nancy McTague-Stock is a Renaissance woman. Working in drypoint, solar etchings, monotypes, drawings, paintings, and photography, she often starts with one then switches to another, allowing further exploration. “I work in a lot of glaze layers, so it takes a long time to build everything up.” Artist, writer, teacher, mentor, mother, caregiver, and spouse, McTague-Stock has turned a challenging 2020 into a period of reflection and productivity, turning to online teaching in mediums from watercolors to pen and ink to printmaking. “It’s such a wonderful form of human connectivity.”

Growing up on a nature preserve on Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay and now living in Fairfield County, CT, nature has been “constant fodder” for her work. “Sometimes it’s just a glimmer of light, one little leaf, one interesting piece of a broken tree…” The series Propagation, I-IV captures a garden through the moonlight created with powdered graphite and oil paint on Belgian linen. “There’s that sense of nature yet also of man in the outdoor space. There are beautiful luminous things that happen in the outdoors at night. I chose powdered graphite as it gives off this sort of velvety subtle glow.” One senses in McTague-Stock a profound self-awareness, of her art and of her purpose. “I want to be in my studio, I want to be working, mentoring, helping somebody else find their creative life.”

Finding solace in nature, she explores its “mysteriousness, its depth, that one little thing that might spark an idea. And then I become an archaeologist, trying to discover further. I think if I wasn’t an artist I would have been some sort of scientist.” Yet another layer. — R.A.F.

Destiny Palmer

Boston, MA,

destinypalmerstudio.com

Anna McNeary

Providence, RI,

annamcneary.com

Harlan Mack

Johnson, VT,

harlanmack.com

Gabriel Sosa

Boston, MA,

gabrielsosa.com

Adèle Flamand-Browne

New Milford, CT

adeleflamandbrowne.com

Margaret Jacobs

Enfield, NH

margaretjacobs.com

Asata Radcliffe

Portland, ME

asataradcliffe.com

Sumru Tekin

Charlotte, VT

sumrutekin.com

Ryan Adams

Portland, ME

ryanwritesonthings.com

Nancy McTague-Stock

Wilton, CT

nancymctaguestock.com