Edward Hopper à la Gloucester

Cape Ann Museum’s exhibition celebrates the painter’s love for the New England town and his wife, artist Josephine Nivison.

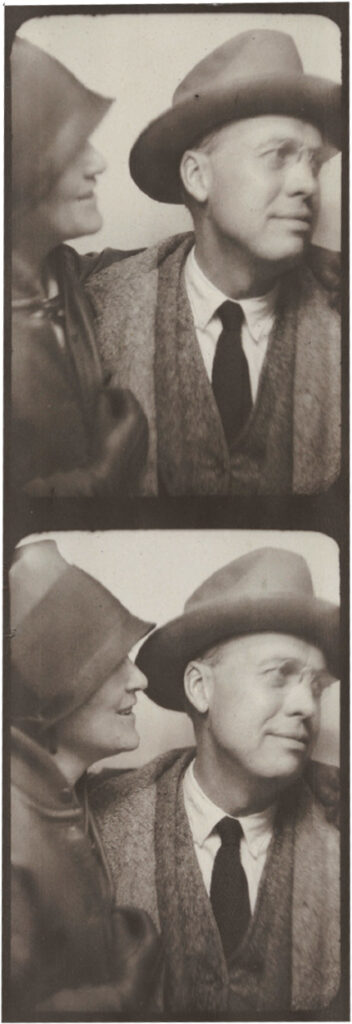

Buying his first car in 1927 indirectly changed Edward Hopper’s career. With the newfound mobility through their secondhand vehicle, he and his wife, artist Josephine “Jo” Nivison, had the freedom to travel across New England and spent many summers in Gloucester, MA where he found a quaint alternative to downtown New York’s bustle. The artist’s transformative seasonal escapades in the Cape Ann town is the subject of an ambitious exhibition at Cape Ann Museum, titled Edward Hopper & Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape, which opens on Hopper’s birthday, July 22nd.

The great painter of American pastoral joy and urban solitude visited Gloucester, MA, for the first time in 1912 upon an invitation from his friend and peer Leon Kroll and returned again with his soon-to-be-wife in 1923 which encouraged the show’s organizers for a centennial celebration of Hopper’s fascination for the town’s unhurried maritime charm. It was this admiration for the refreshing, salty sea breeze and romantically-colored houses that kept the iconic New Yorker returning to the New England enclave numerous times until 1928. Growing up in Nyack, on the banks of the Hudson River, Hopper always saw something in the seaside, perhaps a type of isolation that felt innate rather than chosen. While he didn’t purse his intention to become a naval architect, his paintings explored the unexpected poetry of gargantuan sailing vessels, plain decks penetrating into the placid water, and abstract geometries of sharp-nosed boats. And, Gloucester provided him the stimuli to entrench himself into painting like no other place.

Following the success of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition Edward Hopper’s New York and the Exhibition on Screen’s documentary Hopper, An American Love Story, the exhibition promises a version of the artist distilled from the experience of a particular place. The checklist’s sixty-five paintings, drawings, and prints have been collected on loan from twenty-eight institutions that include the Whitney, Brooklyn Museum, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

New York, where Hopper lived most of his life, was central to the Whitney show, his observations within the city’s skyrocketing transformation illustrating a contemplative extrovert. Cape Ann Museum’s presentation chronicles an artist who found solace in staggered visits to a locale dramatically different than Manhattan’s skyscraper-clad blocks stomped by fast-paced pedestrians. Hopper’s themes of detachment and ennui therefore resonate less explicitly but rather more given and native in his watercolors and oil paintings of abandoned streets, silent sail boats, and houses with unlit windows. Loneliness feels organic, and reverie, commonplace. “New England towns like Gloucester were microcosms of what was happening in America with tightly-knit new immigrants from Italy or Portugal,” told the show’s curator Elliot Bostwick Davis to Art New England. The museum’s director Oliver Barker added: “We have the unique opportunity to tell a story based on a place, surrounded by the artist’s creative catalysts—it’s a story of America in the 20th century underscored by a place of commerce, society, and change.”

Edward and Jo’s annual sojourns at various rentals and artist boarding houses coincided with the years that were fundamental in Hopper’s life and career. At age thirty, he had created his first plein air oil paintings (after his return from Paris) in Gloucester in 1912, followed by those that have the town’s harbor, Italian Quarter, or the mast of a docked vessel as his subjects. The summer of 1923 was also a turning point in his private life. He met Jo who was an artist and actress in the bohemian West Village art circle which was led by their mutual teacher Robert Henri. When they traveled to the town together for the first time in the same year’s summer, Hopper found himself working with watercolor similar to Jo who had already shown her work at various American and European galleries. Their growing love had also poured into their works, most clear from their inclination to both paint Gloucester’s local Baroque style church, Our Lady of Good Voyage. Portuguese Church in Gloucester (1923) renders the building’s two ornate bell towers from afar, the watercolor’s iridescent quality attributing the summer light onto Hopper’s economic gestures. Italian Quarter, Gloucester (1912) from a decade earlier is a medley of architectural geometries—facades, electric poles, chimneys—spearheaded by the forefront house’s unabashed green hue, thickened by oil paint’s binding onto paper.

In 1923, Hopper also made his biggest sale when the Brooklyn Museum acquired The Mansard Roof (1923) for a hundred dollars, ensued by a steady career uplift which led to signing with Frank Rehn Gallery. Hopper’s intention to return to Gloucester in 1924 was met with one condition on Jo’s end—getting married. “The paintings from that honeymoon summer have a unique quality,” said Bostwick Davis. “There is more light and air sweeping across the surfaces with paintings of beachgoers—he scattered colorful umbrellas with many unpainted parts reserved to imply water.” This was also when Hopper was exploring the town’s back alleys and backstreets as much as the waterfront. Bostwick Davis refers to an interview Hopper gave to Time Magazine in the 1950s in which he mentioned his interest in painting the houses when his peers were all looking at the town’s waterfront. “Even when he was painting the water, however, he was more interested in capturing the vessels,” she added. Tall Masts (1912) and Trawler (1923-24) both demonstrate this fascination a decade apart: towering masts pierce into the blue sky in the former oil on canvas while watercolor’s liquid potential yields a romantic portrait of a lonesome vessel in the latter.

As an extrovert, the artist perhaps reveled at unmanned alcoves where the New England luminosity brightened the modest size houses’ colorful facades a few shades lighter. Lighthouses which also anchored Hopper’s New England fascinations entered his lexicon in 1926 during his stays in Rockland, Maine. Their luring ambiguities perhaps attracted him like no other form of structure. Both heavily functional and sculptural, lighthouses were demure witnesses of the harshest of the waves and the calmest sunrises, mystified by their aloof inhabitants and mellow architectures. For 1926, Jo and Hopper situated themselves on Gloucester’s Middle Street, not too far from Cape Ann Museum, when the artist also established an interest in captain houses. The exhibition’s three watercolors from this year show houses named after their owners, Anderson, Abbott, and Tony. “This is when Hopper began building relationships with the local community and actually engage with the houses’ residents,” the curator added.

When Hopper and Nivison returned to Gloucester for the final summer in 1928, they indeed stayed until October when the New England fall’s reds, yellows, and oranges famously blanket the scenery. Freight Cars, Gloucester (1928) embodies such a foliage musing in oil paint, the flatness of commercial vehicles sharpened by the houses’ spiky rooftops, all in brown, in a gentle contrast to yellow nature’s crisp stillness. Hodgkin’s House from this same year was the final house painting Hopper created in Gloucester, an unassuming portrait of a home in which the windows might as well be the eyes of a visage that encapsulates many unknowns within. “Between those sixteen years in which he visited Gloucester, Hopper created a time capsule of the town’s transformation,” Bostwick Davis said, adding “Just within the depiction of the freight yards, there are the signs of industrial modernization and closer to the viewer in the painting, we see those golden grasses typical to New England nature.”