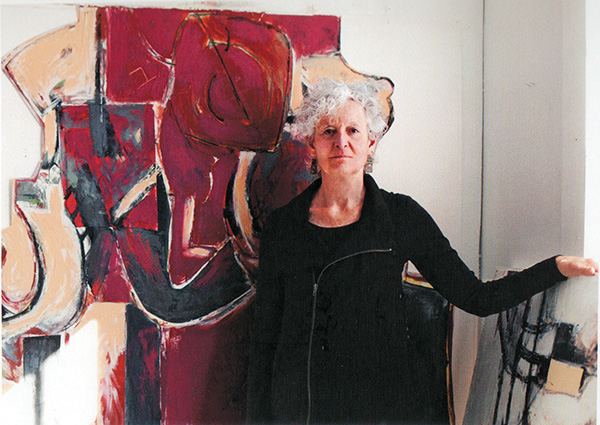

Ruth Mordecai

“That’s where the image starts to disappear,” Ruth Mordecai remarks as she gestures to her large-scale painting, Untitled No. 9 (Black and White), in which two figures hold one another in a full body embrace, at once becoming and disappearing. Part of the series “The Kiss,” this new body of work follows a trajectory that parallels her more than fifty-year career, and yet it explores new emotional territory for the eighty-five-year-old artist: the experience of profound loss. Mordecai lost her husband of several decades, Ed Powers, in 2022. Rendered in black lines emerging out of brilliant white, the abstracted image is anything but linear—like grief itself.

How does one simplify a multitude into its essence? This is perhaps the central question– or one of them–that Mordecai has interrogated since she fell in love with artmaking, as a young woman in her 20s, in a class taught by John Wilson at Boston University. She began with the figure, and now she finds herself there again. Yet this iteration encompasses the many phases of her making, which has included drawing, painting, collage, and sculpture in various mediums, including clay, bronze, plaster, steel, fiberglass and cement. This latest series, on view at Matthew Swift Gallery in Gloucester, MA through November 27, captures the essence of it all: the fluidity of gesture Mordecai has honed over years of questioning and experimentation reflects a clear and consistent voice that is uniquely her own.

Mordecai has a light-filled studio on Cape Ann, where she has lived for the past several decades. (Mordecai and her husband moved to Gloucester after she lived and worked for roughly twenty years at 249A Street in Boston, which she founded with thirty other artists as the country’s first limited-equity artists’ live-work building.) Outside her studio window, boats in Smith Cove shimmered in the sparkling light of a late summer afternoon, the vast ocean just beyond. This turning toward the light–for which the Cape Ann painters have become famous–is so much a part of her work now, and yet it, too, has been explored through her minimalist approach. She considers the move from Boston to Gloucester one of the major turning points of her life, particularly the experience of “going out early in the morning and painting the sunrise,” she says. “It was kind of like I was shot out of a cannon into color.”

What sculpture can’t do, at least not in the same way painting can, is pull light to the surface. Sculpture can dance with light, manipulate it, showcase it, illuminate itself under its gaze; but only color layered onto a surface–ironically–has the capacity to channel light. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Mordecai’s Cape Ann-inspired abstractions of the sunrise. These minimalist landscapes glow from within; as such, they capture the ineffability the artist has danced with over the course of her career.

Even in “The Kiss” series, which marks a return of sorts to her origins, she harnesses light and contrast with what appears to be a spare palette of red, black, and white. “I tend to work that way, from a lot of information into simplified minimal,” Mordecai explains as she sifts through a stack of works on paper. “I came to it from sculpture.” Looking at the embracing figures, I recalled Klimt, and she quickly clarified, grounding herself back to sculpture: “I saw the Brancusi and I thought, if he can do it, I can do it.”

The result—ghostlike mark-making in black emerging into and out of a white or red ground–reflects this exploration of making sculptural gestures on two-dimensional surfaces. “I was kind of at a standstill,” she tells me, recalling the days after the loss of her husband. “I just didn’t know how to proceed. So I went to an earlier figurative sculpture since I’ve always been interested in dance, landscape, figure.”

Referring to Dance, Slab Torso, a 10 x 10 x 7 inches bronze (1983), one can see the origins of this trajectory, a physical process that parallels the action evident in her work. The musculature of her early sculptures is evident throughout the abstracted work as well as her steel sculptures reminiscent of David Smith, who she credits as one of her influences. Looking through her retrospective book Ruth Mordecai, one sees the trajectory from figure to abstracted form, yet the figure was never fully released, even in the seascape-inspired work—it was an ongoing and dynamic presence, carrying the body’s joyful movement through the layers, and years, of light-infused abstraction; the curving line of an inlet mimicking a bending torso.

One is tempted to use gendered terms to describe Mordecai’s thick, gestural lines that give the female form agency not often seen in the art of male artists—more typically, women are monstrous caricatures (think Picasso and cubism) or vessels, submissive objects of beauty. Mordecai’s early sculpture, Life Size Standing Woman #3 (clay, 72 inches high), flouts contrapposto indirectness; instead, she stands Athena-like, forged in strength and agency. This strength is another consistent thread–bold figuration and its abstraction into movement–yet it is anything but rigid. The angular lines suggestive of torso and limbs arc and float. “I think all of my work is generated from something I care a great deal about,” Mordecai says. “About a feeling, probably. And initially when I was a student I thought, the figure is the most complicated thing I can possibly do. If I can do that, I can do anything. And that was the initial motivation. But then it became a vehicle for me to express my love of dance, movement, motion, and then that gestural quality moved into how I interpret landscape and ultimately how I interpreted this new series, with the loss of Ed, into this gestural drawing.”

Above right :Dance, 2023, red oxide acrylic, charcoal, 34 x 42″. Photo: Charlie Carroll.

It all started in John Wilson’s class: “He was so much about, you can get the form and you can get the gradations of light to dark, but if you don’t have a gesture and an emotional connection, you don’t have a work,” she explains. Yet, she adds, “It’s not just figure. It’s stories, symbols that I get connected to. I did an ark for a synagogue commission…, to do the ark for their torah on their bema… Well of course all the symbols and all the research of the six months of doing it just seeped into my work. Then the number seven became important, and then gold, and then purple, and peace doves. So every single thing moves into something else. I mean it’s just all about a life. That’s what Guston said. It’s not a painting, it’s a life.”

Mordecai raised two children while growing a professional career as an artist, and she recognizes that many women of her generation were unable to make substantial strides in that direction. Alicia Ostriker famously wrote, “Art destroys silence,” and this has been true for Mordecai all along. She never stopped questioning, making, showing her work. Ostriker is of the same generation as Mordecai; and while the two women primarily explored different forms in their artmaking careers—Ostriker as a writer, Mordecai as a visual artist—it could be said they have explored similar questions from a deeply emotional and psychological perspective.

Mordecai’s consistent focus and persistence over the years paid off: her work is included in the collections of institutions such as Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Israel Museum in Jerusalem; Cape Ann Museum; Rose Art Museum; and Boston Public Library. She is also featured in Fixing the World: Jewish American Painters of the Twentieth Century, and Tradition and Transformation: Three Millennia of Jewish Art and Architecture, both by Ori Solteis. Mordecai has also found meaning through teaching and mentoring. She attended Bennington College and has a BFA and MFA from Boston University School for the Arts, where she later taught. She has also taught at DeCordova Museum School and the Harvard University Ceramics Studio.

If the impetus to her work could be traced to a single origin, what would it be? “I think it’s my spiritual life. I really do. My mother was a very bright woman, and for whatever reason she was totally engaged in her intellectual life and disengaged from religion as a spiritual practice. And I felt like I was carrying on that search for her.” Mordecai continues to weave that thread into all she does—making work about what matters to her, and to the world: always seeking to bring peace, to connect to others with her art.

Mordecai’s limited-edition book, on sale as part of a fundraiser for the Goetemann Artist Residency, which will also include an exhibition of her work at Rocky Neck Cultural Center, offers a glimpse into her life. As Philip Guston said, “It’s not so much a painting show. It’s a life. A life lived.”