Black Joy and Resistance

Over the course of six weeks in the summer of 1969, the Harlem Cultural Festival brought large, joyful crowds and stellar musical acts—Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King—to Mount Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park). One might have expected such a seismic entertainment event to yield live albums and a concert film. But the Harlem Cultural Festival was overshadowed by Woodstock, which took place just 100 miles away that same summer. With no interest in Black entertainers or happenings in Harlem, even as producers tried to sell the footage as the “Black Woodstock,” the film languished on the shelf for more than 50 years.

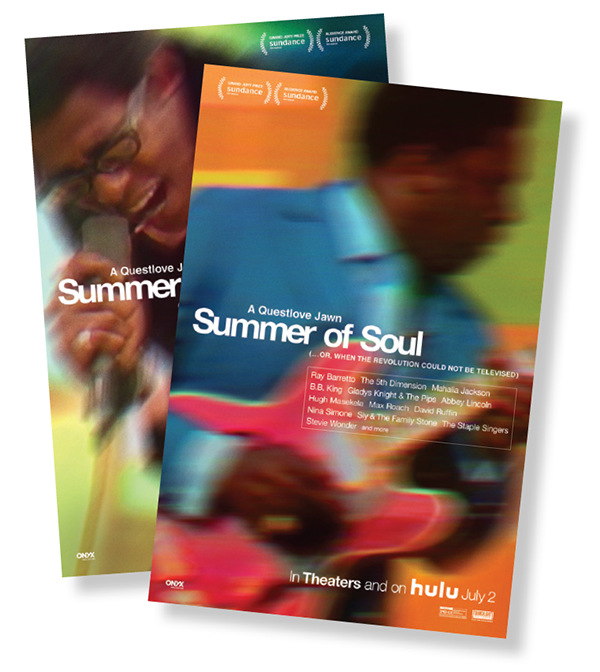

Summer of Soul (…Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised), which opens in theaters July 2 and also streams on Hulu, stands as a remarkable chronicle of the performances and an historical document of the time. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, making his directorial debut, places the concerts firmly in their social/political/cultural context. The shows took place just a year after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. brought protests to the streets of Harlem. They happened as the Black power movement was inspiring a generation’s style of dress, natural hair and other expressions of self-awareness and Black pride. “I knew something very, very important was happening in Harlem that day,” singer Gladys Knight recalls. “It wasn’t just about the music. We wanted progress…we want our people lifting us up.”

Knight is among the performers interviewed who had not seen the concert footage until now. Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr. of the Fifth Dimension are visibly moved as they watch themselves perform a rousing Aquarius / Let the Sunshine In. Just as moving are the now middle-aged concert-goers who reflect on the importance of seeing the shows that summer. There’s footage of New York City Mayor John Lindsay, a Republican who was progressive enough to earn the support of the Black community, hopping onstage with concert organizer Tony Lawrence; and a young Jesse Jackson recounting for the rapt crowd the moment that he witnessed an assassin’s bullet strike down Dr. King. That gutting testimony is followed by Mavis Staples and Mahalia Jackson’s heart-wrenching duet of Dr. King’s favorite hymn, Take My Hand, Precious Lord. The Edwin Hawkins Singers deliver a soaring Oh Happy Day; Hugh Masekela on trumpet blows a blazing Grazing in the Grass; Motown legends Knight and David Ruffin get fans dancing—the range and quality of the music is nothing short of exhilarating. Musa Jackson is moved to tears as he watches Sly and the Family Stone electrify the crowd with Higher. “This is confirmation,” he says. “How beautiful it was.”

When Nina Simone strides onto the stage, one concert-goer recalls “she looked like an African princess.” The Rev. Al Sharpton notes that Simone’s distinctive, deep voice sounded like “hope and mourning,” words that aptly describe this powerful, vibrant film.

Hope and mourning also infuse Ailey, the documentary about modern dance legend Alvin Ailey that opens in theaters July 23. Director Jamila Wignot elegantly and eloquently blends performance, poetry, and social consciousness to craft an impressionistic portrait of the artist and his time that’s reminiscent of I Am Not Your Negro, the 2016 film about writer James Baldwin.

Archival footage and audio recordings of Ailey trace his impoverished childhood in Texas as the only child of a hardworking single mother

to his pioneering choreography that explored identity—“I am,” notes dancer Sylvia Waters—and paid homage to the scope of the rural Black experience, particularly the Black woman’s. Besides clips of Ailey’s signature masterpiece Revelations, there is stunning footage of principal dancer Judith Jamison, who took over as artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) following Ailey’s death at 58 from AIDS complications in 1989, performing Cry, which Ailey dedicated to his mother and Black women everywhere.

Smithsonian Institution, All rights reserved. Courtesy of NEON.

The documentary is framed by the present AAADT rehearsing a new biographical performance piece about Ailey, one part of which is set to Nina Simone’s impassioned Feeling Good. Interviews with dance luminaries such as Jamison, Carmen De Lavallade, and Bill T. Jones offer context and insight into the gay yet intensely private Ailey who experienced mental and emotional turbulence as the demands of his artistry and his fame threatened to eclipse other parts of his identity. Ailey is a dazzling, affirming, and essential portrait of an artist who both reflected and transcended his time.