Six Not to Miss

This summer and fall, several prominent regional galleries and museums are celebrating the return of “art in person” with exhibitions acknowledging historically under-represented artists and mediums.

Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories

at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

October 10, 2021–January 17, 2022

Upending expectations of what constitutes “important” art as well as how quilts are ordinarily displayed in museums, this exhibition emphasizes the significance of the deeply personal narratives and histories that handmade quilts and coverlets express. As organized by the curators, a complex record of American culture emerges from seven thematic sections comprising multiple perspectives. Quilts have been used in the North American home since the 17th century, and the many-voiced story that their intricate, tactile materiality tells has evolved alongside the history of the nation. Visitors will see and hear from artists, educators, academics, and activists while being treated to dazzling works from an under-recognized diversity of artistic hands and minds from the 17th century to today, including female and male, known and unidentified, urban and rural makers; immigrants; and Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian, and LGBTQ+ Americans.

Not to be missed is Pictorial Quilt (1895–98) by Harriet Powers. Born into slavery in 1837, Powers made use of appliqué techniques and storytelling often found in the textiles of Western Africa, which would have typically been created by men. Pictorial Quilt employs semi-abstract narrative design in a potent juxtaposition of folklore, Biblical stories, and real-life tales. Among other highlights are Bisa Butler’s To God and Truth (2019), a vibrant and elaborately patterned quilt based on an 1899 photograph of the Morris Brown College baseball team, and Carla Hemlock’s Survivors (2011–13), in which figures and names of 48 First Nations and Indigenous groups that survive today are stitched around a traditional pattern. The MFA has positioned the work to tell inclusive, human stories that link us across time and articulate a rich, and richly complicated, story of our shared history.

On the Basis of Art: 150 Years of Women

at Yale University Art Gallery

September 10, 2021–January 9, 2022

Tin cans, bed springs, and blown glass tangle, hover, and spin in Judy Pfaff’s 1990 sculpture Straw into Gold, one of nearly 80 exhibited in On the Basis of Art: 150 Years of Women at Yale. Pfaff’s stationary whirlwind of alternately tangled and geometric wires catches and balances the domestic (food cans and bedsprings) with the fine (handblown glass), while the title invokes the triumphant challenge of patriarchal hegemony via the fabled girl imprisoned by a king until she proves her father’s claim that she can spin pure gold from straw.

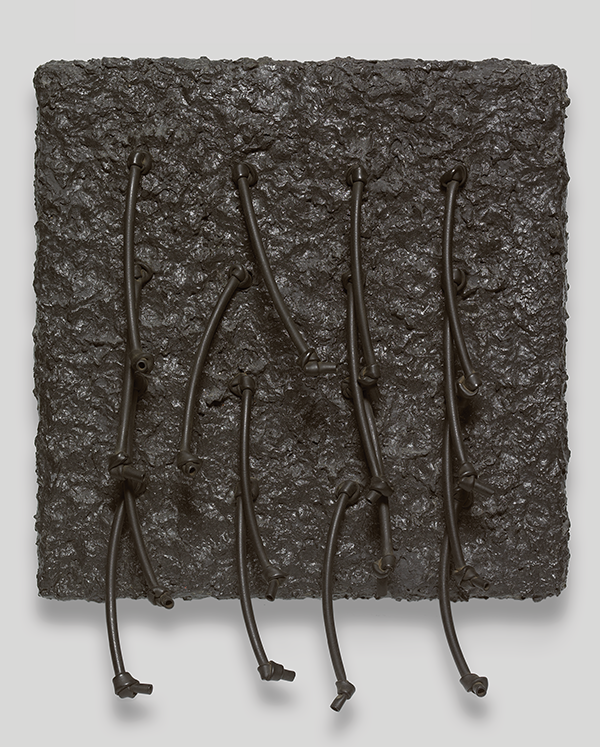

The show’s title references the landmark 1972 U.S. federal law “Title IX,” which mandated that no one could be discriminated against “on the basis of sex” in any educational program receiving federal financial assistance (and which, incidentally, forced the Yale School of Art to hire full-time female faculty beginning that year). Women began attending art classes at the Yale School of the Fine Arts when it opened in 1869, though it took another 100 years for the institution to decide, by a secret vote in 1969, to admit women to Yale College proper. The show features works from the Yale University Art Gallery beginning with Josephine Miles Lewis, the first student, male or female, to be awarded a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree (in 1891). Among the nearly 80 other artist-graduates are Eva Hesse (whose untitled black, asphalt-like wall sculpture remains as stolid and confrontational as it did in 1967), Sylvia Plimack Mangold (whose deadpan depictions of empty floors and mirrors helped redefine the scope of late 20th century abstraction), Jennifer Bartlett, Howardena Pindell, Roni Horn, Maya Lin (who designed the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington D.C.), and Rina Banerjee, whose 2010 collage/screen print Dangerous World finds a ragtag family of female characters treading blood within a world as whimsical as it is horrific.

Deana Lawson

at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

November 3, 2021–February 27, 2022

The first museum survey dedicated to the work of Deana Lawson (b. 1979) surveys the celebrated artist’s riveting photographs from 2004 to the present. Collected by MoMA, the Guggenheim, and Whitney Museum, Lawson has rocketed to the forefront of contemporary photography through a wholesale reinvention of the photographic representation of Black identities. Seemingly documentarian yet invented, at once intimate, unsettling, formalist, and surreal, her methods yield complex narratives of family, love, confrontation, and desire. Lawson’s approach, which spans multiple photographic languages including the family album, studio portraiture, staged tableaux, documentary pictures, and appropriated images, destabilizes the notion of photography as a passively voyeuristic medium. This is work that pulls you in at first with a seemingly quirky (if riveting) mix of oddness, honesty, and artifice, only to transform before your eyes into art that feels powerful, inevitable and exactly right. A fully illustrated scholarly catalog accompanies this exhibition.

Titian: Women, Myth & Power

at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

November 3, 2021–February 27, 2022

In an epic event for the history of painting, six monumental, thematically linked Titian masterpieces are being reunited for the first time in five centuries in an international traveling exhibition making its sole (and final) stop in America at the Gardner. Thanks to an unprecedented loan from the UK’s Wallace Collection, the Gardner’s recently cleaned and restored Rape of Europa will be reunited with its “pendant,” Perseus and Andromeda, which Titian conceived of as its counterpoint. The pair joins the complete series of six great poesie, or “poem-pictures” commissioned from Titian by King Philip II of Spain and painted between 1551 and 1562, when Titian, then considered the world’s greatest painter, was at the height of his powers. Inspired by mythological scenes from Ovid’s The Metamorphoses, the commission was a milestone in Titian’s career, and he was conscious that he was creating something unprecedented and for the ages. The exhibition reunites the Gardner’s Europa and the Wallace Collection’s Perseus and Andromeda with Danaë, (The Wellington Collection, Apsley House); Venus and Adonis (Museo del Prado, Madrid); and two “Dianas,” Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto, jointly owned by the National Gallery, London and National Galleries of Scotland. It’s hard to imagine this great cycle of paintings being shown together again in current lifetimes, if ever at all.

By Her Hand, Artemisia Gentileschi and Women Artists in Italy 1500–1800

at Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

September 30, 2021–January 9, 2022

Women artists played a vibrant yet overlooked role in the Italian art world around 1600, and in our time Artemisia Gentileschi has emerged as the most celebrated female painter of the period. This exhibition explores how women artists succeeded in the male-dominated art world of Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and El Greco, only to be mostly forgotten by art history until recent times. Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as a Lute Player will be shown beside the related Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, on loan from the National Gallery, London—a rare opportunity to see these important paintings side by side. Yet no exhibition of Gentileschi’s work would be complete without explicit reference to the decapitation of a brutish male figure by an avenging female, and Gentileschi’s Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes from the Detroit Institute of Arts, will also be on view. Although it’s taken centuries, Gentileschi’s genius, fueled by rage (she was raped by her mentor at 18 and tortured to prove she was telling the truth during the public trial that sank her reputation), has grandly prevailed. Beyond Gentileschi, the exhibition celebrates a diverse and dynamic group, including 16th century court painter Sofonisba Anguissola, 17th century Venetian pastelist Rosalba Carriera, and many talented yet virtually unknown Italian women artists being rediscovered at last.

Uncommon Threads: The Works of Ruth E. Carter

at New Bedford Museum of Art

May 1–November 14, 2021

Academy Award-winning costume designer Ruth E. Carter is known for her work on more than 30 years of films, including Black Panther, Do the Right Thing, and Roots (reboot). Carter has dressed thousands of actors, including Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Jane Fonda, and Oprah Winfrey. She worked on Steven Spielberg’s slave-revolt saga Amistad and costumed-designed multiple films for Spike Lee. The Massachusetts native, now 61, is being given a retrospective presentation of her iconic costumes that also showcases her extensive research and design process through sketches, mood boards, reference photographs, and ephemera. The exhibition underscores Carter’s creative role during an evolutionary period of Hollywood’s treatment of the lives of Black men and women. A Hampton University graduate, Carter was born in Springfield, MA, and following a stint as a costume apprentice for the Santa Fe Opera, moved to L.A. to work with Lee. In 2019, Carter became the first African American to win an Academy Award for Best Costume Design for Black Panther. The exhibition emphasizes how the “stories” that film costumes tell can ripple out to influence music, fashion, and culture and how we craft and understand the underlying narratives shaping contemporary life and our understanding of history.